Let me state the obvious, the Iran sanctions are the biggest oil story of 2018, period. The prospect of losing out millions of barrels of oil daily shook the market and was a part of crude’s surge by roughly 15 USD per barrel this year (as of today, the 2018 Brent Dated average is 71 USD per barrel against 54 USD per barrel in 2017). The closer we get to November 4th, the more agitation and market jitter. Iran has also made the global crude market very difficult to read and predict, to put it in the words of Saudi Aramco CEO Khalid al-Falih, 2019 will be a “very difficult year to predict” both from the supply and demand sides. Underscoring the complexity of anticipating future developments, top trading companies have an entirely different view on how markets would react to Iranian crude gradually evaporating from the supply side.

During a recent conference in London, top-ranking representatives of leading trading companies articulated their expectations on the average 2019 Brent price. Ian Taylor of Vitol said $65 per barrel, Torbjörn Tornquist of Gunvor stated $70-75 per barrel, Jeremy Weir of Trafigura went with $80-85 per barrel, whilst Alex Beard of Glencore forecasted $90-95 per barrel. It seems that someone from the respectable four will be right – the only problem is that the other three will be inevitably wrong, despite having the widest and most thorough market knowledge one can get. This volatility we must accept as an essential element of the crude game, however,…

Let me state the obvious, the Iran sanctions are the biggest oil story of 2018, period. The prospect of losing out millions of barrels of oil daily shook the market and was a part of crude’s surge by roughly 15 USD per barrel this year (as of today, the 2018 Brent Dated average is 71 USD per barrel against 54 USD per barrel in 2017). The closer we get to November 4th, the more agitation and market jitter. Iran has also made the global crude market very difficult to read and predict, to put it in the words of Saudi Aramco CEO Khalid al-Falih, 2019 will be a “very difficult year to predict” both from the supply and demand sides. Underscoring the complexity of anticipating future developments, top trading companies have an entirely different view on how markets would react to Iranian crude gradually evaporating from the supply side.

During a recent conference in London, top-ranking representatives of leading trading companies articulated their expectations on the average 2019 Brent price. Ian Taylor of Vitol said $65 per barrel, Torbjörn Tornquist of Gunvor stated $70-75 per barrel, Jeremy Weir of Trafigura went with $80-85 per barrel, whilst Alex Beard of Glencore forecasted $90-95 per barrel. It seems that someone from the respectable four will be right – the only problem is that the other three will be inevitably wrong, despite having the widest and most thorough market knowledge one can get. This volatility we must accept as an essential element of the crude game, however, there are some things which can be forecasted with a quite high probability rate.

I. Get cheap

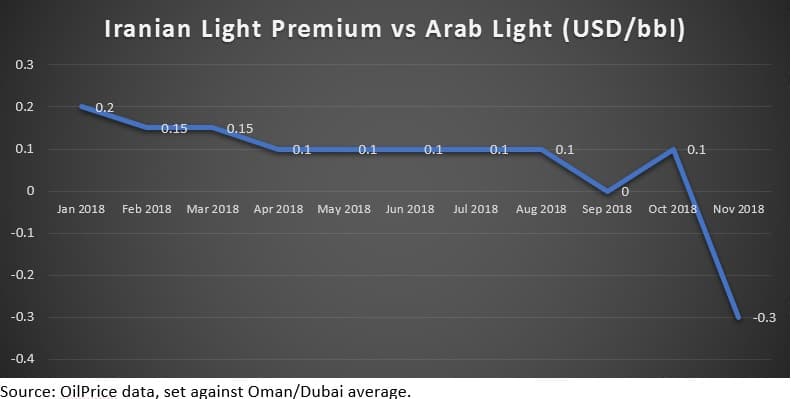

Before Tehran even considers concealing cargoes, finding alternative shipping routes, and ingenious ways to circumvent U.S. sanctions, it ought to acknowledge a new reality – Iranian crude will be very cheap from now on. One can already see the effects of U.S. sanctions on NIOC’s OSPs during the past few months. For the first time in the past twenty years, the OSP-based Iranian Light Premium to Asia Pacific fell to a -0.3 USD per barrel against the Arab Light, which was traditionally priced lower because its Sulphur content is higher than that of Iranian Light. Even during the previous round of sanctions between 2012 and 2015 Tehran managed to avoid such steep discounting. Similarly, Iran’s other flagship grade, Iranian Heavy, witnessed similar pricing drops in NIOC’s November OSP.

(Click to enlarge)

Source: OilPrice data, set against Oman/Dubai average.

II. Get invisible

Statistics paint a skewed picture of how Iran reacts to the sanctions. If one is to believe available shipping data blindly, October 2018 loading volumes from Iranian ports will end up within the 1.1 – 1.2 mbpd interval, meaning that within the timeframe of just 12 months Iranian crude exports have dropped by 1 mbpd. We, however, should include volumes that are shipped by the National Iranian Tanker Company (NITC) which has moved approximately 10 tankers during the same period – unfortunately for the non-prejudiced observer, these have stopped transmitting GPS transponder signals quite some time ago, so no one really knows where they are. Let us assume that NITC tankers do transport oil, indiscernibly, which would mean that Iran’s exports are actually 700-750 kbpd higher than the “official” shipping data would assume, hovering at around 1.8-1.9 mbpd.

The impossibility of precisely pinpointing where NITC’s fleet is heading means that Tehran can use several back-door entrance options to its traditional markets. Let’s take China, for instance, which received crude from two NITC-owned and operated cargoes in July-August this year in Myanmar’s oil terminal. The oil was then transported via the Myanmar-China terminal to Petrochina’s 260 kbpd capacity Yunnan refinery. This was still in times when it was possible to precisely locate NITC tankers, now it would be much harder to do, especially in Myanmar which has few political ties to United States and thanks to its strategic partnership with China is not very susceptible to good old U.S. hand-wringing. In total, NITC’s active fleets consists of roughly 50-52 vessels.

III. Get flexible

Middle Eastern oil producers are notoriously rigid when it comes to selling their oil. Does not matter if it is Saudi Aramco, the Iraqi national oil marketer SOMO or the Iranian NIOC, they would stick religiously to their terms and conditions and disregards GTCs that are commonly used between traders. One such requirement stipulates that the Seller is not allowed to resale any volume of non-equity crude it buys from the Buyer. In fact, the Iraqi SOMO has launched a new campaign against a number of its European clients, denouncing their practice of reselling cargoes SOMO has allocated to them exclusively.

NIOC has used the same no-resale clause in its previous practice, now, however, there is little logic in sticking to a rule which only encumbers its dealings. Therefore, Iran is very likely to drop some of its erstwhile rigidity and blaze a trail for more creative solutions. For instance, by creating a trade chain long enough to obfuscate the initial country of origin of the cargo in question, one can easily imagine that “Middle Eastern mixes” or “Heavy Blends” will float around Asia in the upcoming weeks and months. All the more so if the vessels would not be locatable.

IV. Get regional

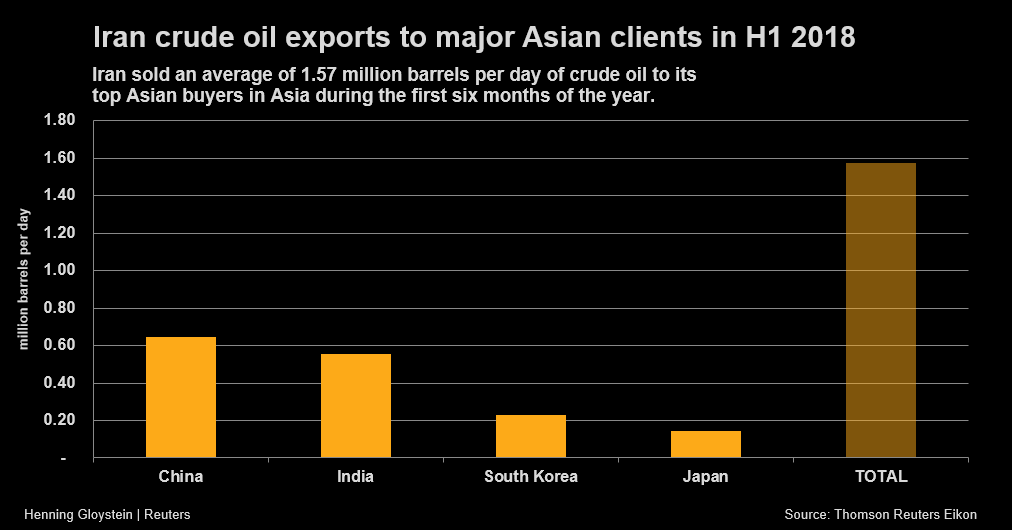

Traditionally, Iran’s crude exports were destined to five main outlets – China, India, South Korea, Japan and Turkey. If one is to add countries of Mediterranean Europe to it, you get a fairly complete vision of where Iranian crude was predominantly supplied. This is no longer the case – every single Mediterranean country has opted out of Iranian purchases (combined with Greek shipping companies quitting the business until sanctions are in power). Moreover, South Korea and Japan, despite a several-month negotiations marathon with Washington, could not secure waivers for further purchases of Iranian crude or condensate and were compelled to comply. As a consequence, Teheran finds itself with a relatively narrow list of potential customers – China and India remains, Turkey is still mired in doubts, whilst Russia’s possible involvement is still a big question mark.

(Click to enlarge)

That Turkey seems likely to get an Iran imports waiver is a lucky confluence of events and good bargaining by Ankara – it conditioned the normalization of relations on Washington granting it some sort of sanctions relief (most likely a waiver for 100-150 kbpd imports). India, repeating its successful avoidance of sanctions in 2012-2015, has already contracted 1.25 mtpa for November (i.e. after sanctions take effect) in the person of Indian Oil Corporation and Mangalore Refinery and Petrochemicals. Considering how much the Indian rupee has dropped this year, it would make even commercial sense to switch to rupee trading. China, too, is opaque – despite public assurances that state refiners will not buy Iranian crude in November, a record load of 22 million barrels of oil is heading now to northeastern port of Dalian, close to many independent refineries.

Media outlets have been discussing the prospect of Russia selling Iranian oil in order to avoid direct U.S. sanctions, however, there are multiple reasons to be skeptical about such developments. First, no one would buy these volumes were Russian traders to offer them on the market – Europe’s compliance is total. Reports claimed Russian companies might use it for refinery purposes at home, freeing up space for exports of home-produced crude, however most refiners are concurrently exporters, too, and not one of them would risk bringing on further U.S. sanctions on themselves. Still, Russia has been eager to switch to oil payments in rubles, and it might use smaller, less externally vulnerable companies to undertake some sort of “oil-for-goods” scheme.

V. Get storage

If you’ve wondered why of the total NITC fleet of some 50 vessels (the world’s second-largest VLCC fleet, by the way) only a dozen is currently active, storage is the correct answer to your question. Similarly to Iran’s reaction during the 2012-2015 sanctions period, Iran has been storing crude in its vessels as a floating storage – by September, at least eight VLCCs have been pinpointed around Iran’s main terminals of Kharg Island and Soroosh, storing an estimated 15-17 million barrels of crude. It has to be said that in 2012-2015 the vast majority of floating storage was condensate which Iran simply had nowhere to refine, but with the commissioning of the Persian Gulf Star Refinery in Bandar Abbas, it can easily refine it into gasoline, thus most of the 2018 floating storage will most likely be crude.