In the past two weeks, we have analyzed the prospects of US crude exports to Europe and Asia, both with its region-specific challenges yet both holding distinct promise for American exporters. The US’ relationship with Latin America differs in nature – instead of a burgeoning romance it might be likened to a decades-long marriage when both partners need each other yet are on the verge of a rupture. One cannot compare the ties binding together the US and Latin America to any other intercontinental relationship, primarily because no other regions have a history of oil production that long-standing and close.

It was the US business that stood behind Mexico’s first-ever exploration well, first production and first exported volumes (in 1911). The same is also true for Venezuela whose early 20th century “oil rush” was a US-led enterprise. Yet many Latin American countries are tired of Washington’s hard-line treatment and found a new strategic partner in China, a country that sees its place as that of a country “undergoing a similar stage of development and facing tasks similar” to the ones South American nations face. Add to this Russia which has made inroads into South America largely thanks to personal ties built with Venezuelan and Bolivian leaders and you have a recipe for a proxy clash.

The Venezuelan issue pervades America’s attitude towards Latin America – it rendered tattered relationships even more ramshackle, all the while creating new partnerships with countries…

In the past two weeks, we have analyzed the prospects of US crude exports to Europe and Asia, both with its region-specific challenges yet both holding distinct promise for American exporters. The US’ relationship with Latin America differs in nature – instead of a burgeoning romance it might be likened to a decades-long marriage when both partners need each other yet are on the verge of a rupture. One cannot compare the ties binding together the US and Latin America to any other intercontinental relationship, primarily because no other regions have a history of oil production that long-standing and close.

It was the US business that stood behind Mexico’s first-ever exploration well, first production and first exported volumes (in 1911). The same is also true for Venezuela whose early 20th century “oil rush” was a US-led enterprise. Yet many Latin American countries are tired of Washington’s hard-line treatment and found a new strategic partner in China, a country that sees its place as that of a country “undergoing a similar stage of development and facing tasks similar” to the ones South American nations face. Add to this Russia which has made inroads into South America largely thanks to personal ties built with Venezuelan and Bolivian leaders and you have a recipe for a proxy clash.

The Venezuelan issue pervades America’s attitude towards Latin America – it rendered tattered relationships even more ramshackle, all the while creating new partnerships with countries hostile to the Maduro regime. The Trump Administration first sanctioned Venezuela’s banking and gold-mining sectors, then targeted PDVSA by barring it from any USD-denominated deals and freezing its assets in the US. The US’ last move was to levy an embargo on any commercial activity with Venezuelan state-owned companies and considering Special Adviser John Bolton’s firmness that similar sanctions vis-à-vis Nicaragua and Cuba worked, so these would, too, there is surely more to come.

Condemnation from the UN Human Rights chief notwithstanding, the plan has largely worked as US refiners have stopped taking in Venezuelan crude in March 2019, fully complying with the US Treasury’s sanction deadline. It is worth pointing out that in 2018 Venezuela exported 0.5mbpd of crude to US Gulf Coast refiners, being the US’ second-largest supplier of heavy crudes. Venezuela’s exports have dropped below 1mbpd for some time it seems, oscillating between 0.7-0.8mbpd in the past couple months. China remains the only reliable buyer of Venezuelan crude, albeit using Malaysia recently as a blending hub to obfuscate the actual origin of the crudes it refines (hence boosting Kuala Lumpur’s import volumes).

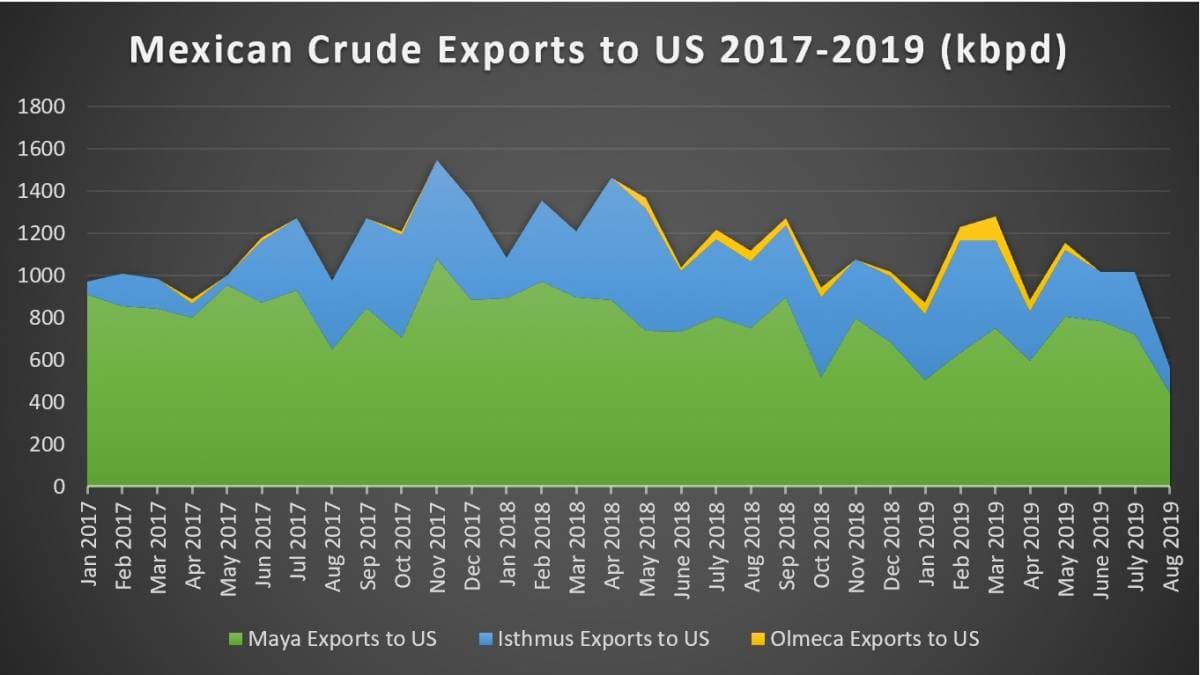

To compensate for the loss of 500kbpd heavy imports to the USGC – much cheaper than regional peers due to its relative quality inferiority to others – remains a substantial challenge for American refiners. One would expect nearby producers of heavy barrels to step in – yet Mexico and Ecuador have actually seen their exports to the US drop this year (compared to the annual 2018 average), preferring to send their barrels to Southeast Asia. The drop in Mexican imports is somewhat paradoxical as US suppliers continue to play a major role in the energy self-sufficiency of Mexico, exporting finished gasoline and distillate fuel oil to Mexico.

Last year US importers took in 1.178mbpd of Mexican crudes, this year the January-August tally stands at exactly 1mbpd. The heavy sour Maya still makes up some 70-75 percent of total US exports from Mexico, while Mexico’s sweeter grades Isthmus and Olmeca have almost evaporated from the US market with ample US replacements rendering them unnecessary. Given the abundance of ample shale crude in the US’ southern states, one might expect that the adjacent Mexico might in some of the United States’ surpluses if they are subject to seasonal price swings, yet that prospect seems to have faded with the election of AMLO and his subsequent (somewhat quixotic) drive to reduce Mexico’s dependence on the United States.

Overall US exports to South America have grown over the past few years – starting from 92kbpd in 2017 all the way to the YTD average of 140kbpd. New horizons have been reached, US exporters delivered the first-ever cargo to Uruguay in March 2018 (and have added a further three since), Chile joined the club in October 2018 and has seen the arrival of 16 WTI and Bakken cargoes since. Colombia stands out herein as the only Latin American country that has managed to simultaneously increase its exports to the United States and its imports from there. A considerable feat against the background of gradually declining production, Colombia managed to pull it off by letting go of its past supplies to European (primarily Spain) and Latin American (Aruba, Peru) customers and dropping India from its priority outlet list.

Colombia and its national oil company Ecopetrol have managed the sanctions-induced Venezuelan supply shortage issue quite well, adapting to the seasonal demand surges in the United States and China. Increased demand for Vasconia and Castilla Blend led to the appreciation of Colombian crudes, with Vasconia rising to highest in years against Dated Brent futures. Right now, the 23° API and 1 percent Sulphur Vasconia is traded at a $-1.25 per barrel discount to December ICE Brent, whilst just 3 years ago the discount was as wide as $-6 per barrel. This is going to change as IMO 2020 inevitably pushes Colombian prices down – especially that of the 2 percent Sulphur Castilla Blend.

Vasconia FOB Covenas vs Brent Futures Strip Differential 2015-2019.

Absent any major breakthrough on the US-Venezuela track, Brazil will rise in importance for US oil firms in the coming years. It might not seem as if the United States were the primary aim of Petrobras – just look at the NOC’s lease of 2 MMbbl worth of storage capacity in Qingdao, China – yet Brazil also needs to keep its exports diversified. Thus, the US will remain the second-largest export outlet for Brazil and will most probably reach a higher export ratio further on than the 12 percent in 2018. With President Bolsonaro committed to “get tough with China” (and potentially antagonizing the Chinese political elites), political developments might also fortify the US-Brazil partnership.

The ongoing transformation of Argentina’s export streams will most probably decrease the volumes exported to the United States. Up to now, US refiners in Texas and California have been taking 2-3 cargoes a month of 24° API Escalante, a prized grade due to its low Sulphur content of 0.2 percent. Yet as time goes on Medanito, Argentina’s shale grade with a 35° API density and 0.4 percent Sulphur, will become the Latin American country’s prime export grade. As Vaca Muerta output ramps up, Medanito is expected to get lighter and reach an average API density of 40° in a couple of years, rendering it rather uneconomic for US refiners who are anyway awash with light shale crude from domestic producers (all the more so as new Permian Basin streams get increasingly lighter, too).

All in all, America is faced with ambivalent prospects in Latin America. It has erased Venezuela off its crude world map, whilst continuing to rely on Mexico and Colombia on much-needed heavy barrels. Both countries are going through a seemingly terminal process of production decline (Mexican output has had 15 consecutive year-on-year drops) and even if there are some recent discoveries in Mexico, they tilt heavily towards the lighter side (Ixachi at 42° API, Mulach at 38° API). Strengthening the cooperation between the US and Brazil seems reasonable and feasible, yet even there US buyers would have to compete with Chinese and Indian peers. As for US crude exports to South America, they will edge higher, yet without one single huge outlet for it.