Mexico’s new president Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, casually abbreviated as AMLO, has now been in office for a month. Despite running a powerful campaign, styling himself as the only candidate who, among other things, could rebuild Mexico’s oil sector so that it stops generating losses, bounces back production-wise and repositions itself as an exciting outlet for investors. AMLO even promised to follow the footsteps of Lázaro Cardenas (who nationalized Mexico’s oil industry in 1938), although he carefully selected his wording on that point so as not to scare off oil majors with a stake in the game. A month into his presidency, it seems Lopez Obrador bring a new spirit to the complex Mexican political and economic system, but is unlikely to become the revolutionary figure that many of his supporters believe him to be.

The oil reform of President Lopez Obrador is multi-pronged and covers almost all aspects of Mexico’s petroleum industry. It aims to refurbish the downstream segment by more than doubling refinery utilization rates, increasing fuel self-sufficiency and building a new state-of-the-art refinery, whilst ramping up upstream activities with an upgraded CAPEX budget and new projects coming onstream within three years. This reform comes following 14 consecutive years of falling production and a refinery throughput decline of some 40 percent in just 10 years.

(Click to enlarge)

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2018.

Despite the…

Mexico’s new president Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, casually abbreviated as AMLO, has now been in office for a month. Despite running a powerful campaign, styling himself as the only candidate who, among other things, could rebuild Mexico’s oil sector so that it stops generating losses, bounces back production-wise and repositions itself as an exciting outlet for investors. AMLO even promised to follow the footsteps of Lázaro Cardenas (who nationalized Mexico’s oil industry in 1938), although he carefully selected his wording on that point so as not to scare off oil majors with a stake in the game. A month into his presidency, it seems Lopez Obrador bring a new spirit to the complex Mexican political and economic system, but is unlikely to become the revolutionary figure that many of his supporters believe him to be.

The oil reform of President Lopez Obrador is multi-pronged and covers almost all aspects of Mexico’s petroleum industry. It aims to refurbish the downstream segment by more than doubling refinery utilization rates, increasing fuel self-sufficiency and building a new state-of-the-art refinery, whilst ramping up upstream activities with an upgraded CAPEX budget and new projects coming onstream within three years. This reform comes following 14 consecutive years of falling production and a refinery throughput decline of some 40 percent in just 10 years.

(Click to enlarge)

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2018.

Despite the state of the industry, Lopez Obrador has a fair chance of doing better than his predecessor Enrique Peña Nieto who opened up Mexico’s oil to foreign investment, yet oversaw a 25 percent drop in overall crude output. Fighting oil theft (by the so called huachicoleros) is a good way to start, with annual losses from these thefts reportedly amounting to $3 billion. AMLO has begin to fight this by ordering the army to take over the supervision of Mexico’s refineries and terminals. Although it does strike an eerily similar chord to what has been going in Venezuela under President Maduro, it might not be all that bad. If AMLO manages to eke out institutional theft (allegedly 80 percent of all theft cases), it could substantially boost his image both internally and externally.

AMLO’s plans to refurbish the Mexican downstream sector are definitely timely, but appear to be overly ambitious. Pemex’s refinery capacity utilization rate has dropped to roughly 30 percent in recent times – a whopping 50 percent drop from historic highs. If we are to look at all six refineries in Mexico (Salina, Tula, Cadereyta, Salamanca, Minatitlan, Ciudad Madero) with a total refining capacity of 1.55 mbpd, the average fuel oil yield is some 34-35 percent. Just to give you a sense of how big a number that is – the average USGC refinery yields 4-5 percent, whilst an average European one yields 9-10 percent.

Pemex has countered this problem by importing light Bakken grade crude from the United States in autumn to increase refining margins, which otherwise would be naturally gravitating towards heavy losses. Even though President Lopez Obrador has criticized this mechanism on several occasions, he allowed US crude imports to continue in 2019, albeit at a level preliminarily capped at 93kbpd. Yet even this would bring refinery throughputs in 2019 to 700-800kbpd, lagging massively behind the administration-set refinery run target of 1.5mbpd (90 percent of refinery capacity at that time). Moreover, AMLO wants to build a new refinery, Mexico’s largest, in his home state of Tabasco. This project will have to be coupled with closures of the least profitable refineries – otherwise it would only inflate further Mexico’s already bloated workforce (Pemex now comprises 128 000 employees).

The transformations in Mexico’s downstream sector ought to be buttressed by upstream investments prioritizing light crude developments. Despite some success stories, which largely fit into the one-off category – like the recently discovered Ixachi field (wielding 40-41° API crude) whose reserves were increased from the initial 366mboe to more than 1bboe – Mexican light crudes are waning. With light crude refinery intake falling from 616kbpd three years ago to 344kbpd now, one can understand why Mexico’s falling total production is largely a result of light streams getting increasingly depleted, whilst heavy streams remain stable. Pemex’s own efforts to lighten up Mexico’s crude slate are insufficient and suffer traditional budget constraints – half of its 2019 upstream budget will be spent on maintaining output in traditional fields like Ku-Maloob-Zaap, Cantarell or Yaxche, with heavy and sulphurous crude.

Things beyond Mexico’s reach, i.e. shifts in international oil trade in general and the ongoing Canadian oil squeeze in particular, also complicate matters further. Canada produces similarly heavy crude, however, due to insufficient pipeline infrastructure is compelled to sell it at wide discounts – hence, in H2 2018 the premiums paid for the Mexican Maya skyrocketed out of the regular interval of -2 to +2 USD per barrel and reached a record +10 USD per barrel in November. Moreover, as Mexican crude is sold under complex formulae, the appreciation of US sour grade WTS, which is included in the heavy sour price calculations has pushed Maya upwards.

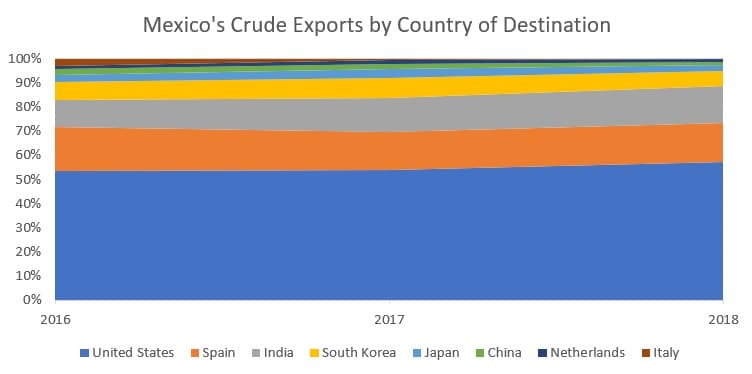

By means of the K-factor, a pricing adjustment tool that Pemex uses to react on external market changes, Mexico can partially mitigate the adverse effects – i.e. in November 2018 the K-factor reached a five-year high of 5.35 USD per barrel, yet that is simply not enough. As a consequence, refiners in the United States take in less Mexican crude than previously, opting for the cheaper Canadian grades instead. This is all the more so worrying as Maya makes up for 94 percent of Mexican crude exports and there are very little light stream flows taking place. In fact, only one Olmeca cargo has left Mexico’s ports throughout 2018 and Pemex officially stipulated a halt to its light exports in August 2018.

(Click to enlarge)

Source: OilPrice data.

All in all, it is difficult to see where the new government expectations of an annualized reserve replacement rate of 200 percent, a crude production of 2.4mbpd in 2024 (against the 1.8mbpd now) and a refinery throughput rate of 1.5mbpd come from. AMLO’s oil sector overhaul is a highly ambitious and much-needed endeavor, however, if the downstream and upstream policy are not dovetailed well enough, the result will be an utter mess. Taking into consideration Pemex’s $106 billion debt liabilities and US rating agencies threatening to downgrade it to junk category if the current policies continue, the assistance ought to come from abroad. But AMLO is unlikely to support international involvelment. Lopez Obrador has cooled foreign interest by declaring a three-year hiatus on all deepwater and onshore exploration contracts to “judge the results of the ones already awarded”. Keep your fingers crossed for Mexico…