Natural production declines, the price drop of 2014-2015, the status of a national cash-cow, lack of sophisticated EOR technology, regular policy U-turns on foreign investment – it is difficult to pick the single most important factor that has contributed to the state PEMEX finds itself in, yet the situation is dire nonetheless.

The Mexican national oil company is hunched under the weight of its debt obligations, generating loss after loss ($7.6 billion in 2018 after a horrendous $14.3 billion in 2017) with no evident way out. The new Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador looks to tackle Mexico’s myriad of oil problems, but at the end of the day he has to sort out PEMEX’s upstream, midstream and downstream travails at the same time.

It might be said that Mexico’s primary problem is falling crude production. Having peaked in 2004, its output more than halved in 15 years, dropping from 3.8mbpd at its peak to the latest lackluster result of 1.69mbpd in March 2019. Were production to be increasing, the market sentiment regarding the Mexican NOC might have been different – absent any miraculous divine intervention, PEMEX will experience all the shades of being in a purgatory before it can actually bounce back a bit from 2022 onwards. Taking center stage in all of this – the Mexican state, root cause of PEMEX’s dire financial condition and its only realistic saviour right now.

(Click to enlarge)

As recently as last week the OECD put out a warning…

Natural production declines, the price drop of 2014-2015, the status of a national cash-cow, lack of sophisticated EOR technology, regular policy U-turns on foreign investment – it is difficult to pick the single most important factor that has contributed to the state PEMEX finds itself in, yet the situation is dire nonetheless.

The Mexican national oil company is hunched under the weight of its debt obligations, generating loss after loss ($7.6 billion in 2018 after a horrendous $14.3 billion in 2017) with no evident way out. The new Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador looks to tackle Mexico’s myriad of oil problems, but at the end of the day he has to sort out PEMEX’s upstream, midstream and downstream travails at the same time.

It might be said that Mexico’s primary problem is falling crude production. Having peaked in 2004, its output more than halved in 15 years, dropping from 3.8mbpd at its peak to the latest lackluster result of 1.69mbpd in March 2019. Were production to be increasing, the market sentiment regarding the Mexican NOC might have been different – absent any miraculous divine intervention, PEMEX will experience all the shades of being in a purgatory before it can actually bounce back a bit from 2022 onwards. Taking center stage in all of this – the Mexican state, root cause of PEMEX’s dire financial condition and its only realistic saviour right now.

(Click to enlarge)

As recently as last week the OECD put out a warning that a further deterioration in PEMEX’s operational stability would bring down the Mexican economy, too. Both investors across the globe and risk assessment companies consider the Mexican government’s initial PEMEX bailout to be agonizingly inadequate – confronted with the task of clearing a net debt of more than $105 billion, it proposed to inject 107 billion Mexican pesos ($5.6 billion) to give the national oil company much needed liquidity. In an attempt to quell the market’s fears about the future of PEMEX, the Mexican finance ministry agreed to allocate another 100 billion pesos ($5.3 billion) from the nation’s stabilization fund, yet still, the government’s response despite the good will demonstrated is dwarfed by the overall indebtedness of the heavily-taxed NOC.

In fact, taxes remain one of the main, if not the foremost, plight of Petróleos Mexicanos. The government taxes around 65 percent of PEMEX’s operational revenues, leaving it with peanuts of erstwhile earnings to dispense with. The Mexican state took $27 billion from PEMEX last year in the form of taxes, more than Cyprus’ or Brunei’s 2018 GDP. Even though the Lopez Obrador administration managed to increase PEMEX’s tax deductions year-on-year, it did so at a quite modest rate, by a „mere” 4 billion pesos (roughly $200 million). For the Mexican NOC to breathe more easily, the state ought to give up on its decade-long tradition of milking PEMEX.

Debt repayments will be almost $9 billion in 2019 alone, to be squeezing PEMEX’s possibilities further next year with $10.6 billion to be paid back. PEMEX international stature was further weakened by Fitch downgrading it to a BBB- credit rating in January, only to be followed by S&P assessing it at BB-. With every credit rating agency assessing PEMEX’s prospects as negative, it is no wonder the PEMEX CFO Alberto Velázquez stated that his company would not issue debt this year. Yet it need not be that depressive for Mexico, primarily because in a stark contrast to fellow Latin American production decline victim Colombia, Mexico is still home to a plethora of very promising projects and its subsoil remains home to billions of untapped barrels of oil.

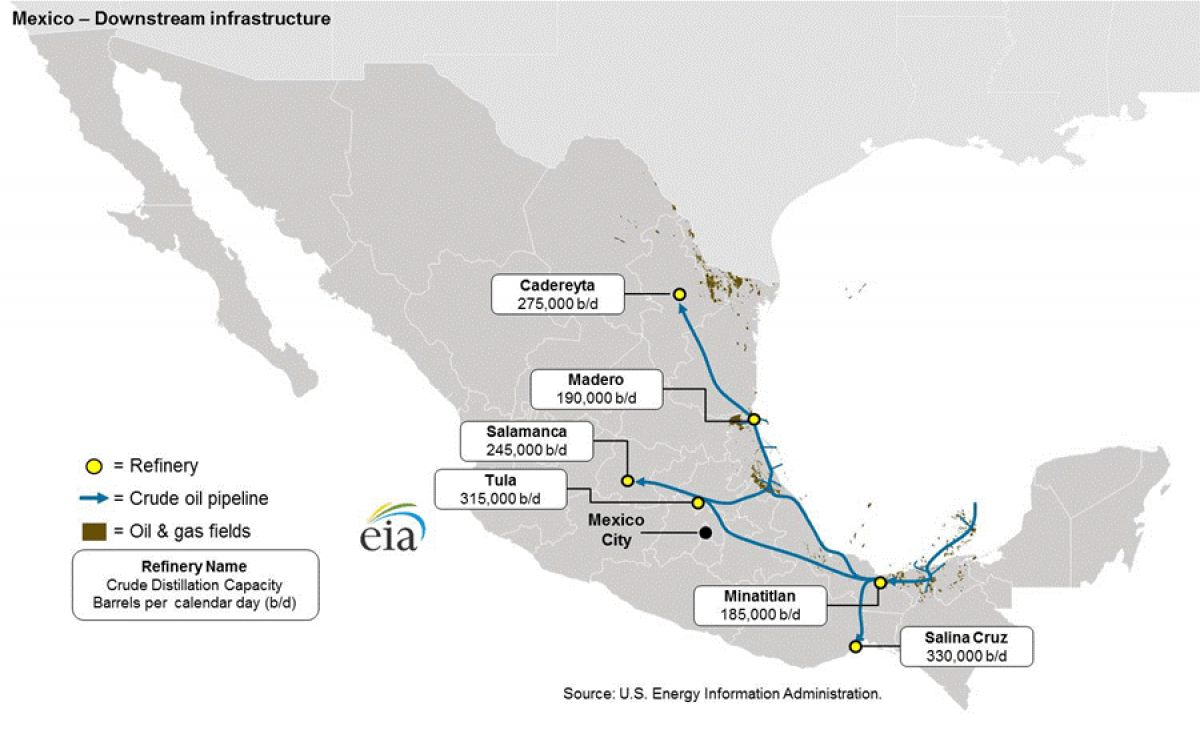

The southern rim of the Gulf of Mexico might kick-start a series of new discoveries. The Ixachi field, Mexico’s largest discovery in more than 20 years, is estimated to contain 3P reserves of 1.3Bbbl – moreover, its crude is significantly lighter than the traditional Mexican f Maya, Isthmus and Olmeca blends(at 40-45 API), thus making it a very suitable feedstock for PEMEX’s largest (and quite unsophisticated refineries) in Tula and Salamanca. In this respect, the Mexican NOC’s vow to drill 506 wells this year as compared to the mere 80 drilled in 2018 is beyond any doubt a laudable step in the right direction.

(Click to enlarge)

Yet unfortunately for everyone, politics is still playing an oversized role in how PEMEX’s travails are perceived, regardless of ideological backgrounds. From a purely political point of view, AMLO is perhaps right in blasting the previous President for failing to halt Mexico’s crude production decline, yet it provides no clarity whatsoever for those companies which did participate in the Peña Nieto-era farm-outs and are now in the development phase of their projects. Investors in past farm-outs are now alarmed that by means of the government’s effectual cancellation of seven long-mooted farm-out tenders, preliminarily scheduled for October 2019.

Instead of the farmout the Lopez Obrador administration is now seeking to effectuate a service contract allocation scheme under which PEMEX would hand out „integrated exploration and extraction contracts” (CSIEE) on 21 onshore and shallow water fields. PEMEX wants to retain the operator status on the fields and remain its owner, yet to outsource all actual work to a third party which would be then remunerated up to 50 percent of production costs, in US dollars for every barrel of oil. It remains to be seen what PEMEX can offer to lure foreign oil majors into such a setup, so far the interest has been tepid at best.

All the more so as the CSIEE seem to make economic sense only when investing into high-risk assets as the suggested cost recovery tariff scheme sees production from 1P reserves at the lowest level, with disbursements edging higher when the contractor produces previously undiscovered or EOR barrels. Another potential challenge might be the size of fields in question – most of them have 2P reserves of 30-60 million barrels with the only notable exception being the 1.89 Bbbl shallow water Akal field, which alone amounts to 69 percent of all 2P reserves offered within the CSIEE procedure.

(Click to enlarge)

Source: EIA.

With a global dearth of sour barrels, USGC refiners would love to see more Mexican crude on the market. US imports of Mexican crude dropped from their all-time high of 1.9mbpd in February 2006 to 0.6-0.7mbpd in recent months and are seeking other development paths as their traditional supply streams from Venezuela and Mexico are drying up. Perhaps taking a larger US stake in Mexico’s offshore would help - yet instead of opening up the Mexican market for anyone interested enough, AMLO is betting on the recovery of debt-stricken PEMEX. That is a serious gamble the collaterals of which might impact adversely the Mexican economy and stymie economic growth.

In the end, the inevitable state bailout of PEMEX will do exactly that. However, the current political elite has to keep it simple not to botch it up even further. Striving to revamp the country’s upstream rules, build a new refinery in Dos Bocas, clamp down on smugglers and thieves and a whole range of others aims, Obrador’s priority list is too wide to fulfill. For instance, AMLO has also been concurrently fighting retailers, allegedly keeping in ever-larger profits instead of lowering prices as per the retail stimulus measures, with the threat of opening a national web of fuel retailers to pressurize private retailers into acting appropriately.

Talking at the same time about attaining energy indepence à l’americaine by the end of his mandate in 2024, AMLO’s numerous promises ring hollow. Mexico imports 70-75 percent of its gasoline, diesel and jet fuel needs, wants to construct a new refinery instead of upgrading the unsophisticated ones and keeps zombie refineries (like the Madero refinery in Tamaulipas state) alive even though they do not work most of the year. To sum up, President Lopez Obrador will struggle really hard to make Mexico great again.