The London stock market, the British pound and the European populace, in general, were buoyed by rumors emerging about London and Brussels closing in on a comprehensive Brexit deal that would allow the UK to leave the European Union on October 31, one hour before midnight. Brexit’s impact on the oil sector is yet to be assessed properly, but so far it seems that the ramifications would only be relatively minor – some trading companies might want to relocate to Geneva, following the footsteps of several investment banks which have downsized their London presence. Yet the British oil industry might indirectly suffer, too, leaving the UK with terminally decreasing oil and gas production volumes.

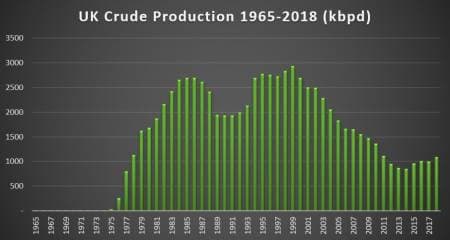

Let’s assume that Boris Johnson clinches a deal with the European Commission, has the Brexit deal approved by the Parliament and the Conservative Party remains in power. This presupposes no drastic policy changes and no tinkering with the oil tax code. If so, Britain’s oil industry has a relatively stable decade ahead of it, having bounced back in 2018 to an average production of 1MMbpd, a level unseen since 2011. Having peaked at 2.9MMbpd in 1999, the UK oil production was assumed to enter a period of precipitated decline, especially so when its annual output started to plummet by some 0.2MMbpd per year in 2009-2011. It bottomed out in 2014 at 0.85MMbpd and thanks to a general oil price recovery and a rather successful cost-efficiency drive managed to get back on the growth trajectory.

Source:…

The London stock market, the British pound and the European populace, in general, were buoyed by rumors emerging about London and Brussels closing in on a comprehensive Brexit deal that would allow the UK to leave the European Union on October 31, one hour before midnight. Brexit’s impact on the oil sector is yet to be assessed properly, but so far it seems that the ramifications would only be relatively minor – some trading companies might want to relocate to Geneva, following the footsteps of several investment banks which have downsized their London presence. Yet the British oil industry might indirectly suffer, too, leaving the UK with terminally decreasing oil and gas production volumes.

Let’s assume that Boris Johnson clinches a deal with the European Commission, has the Brexit deal approved by the Parliament and the Conservative Party remains in power. This presupposes no drastic policy changes and no tinkering with the oil tax code. If so, Britain’s oil industry has a relatively stable decade ahead of it, having bounced back in 2018 to an average production of 1MMbpd, a level unseen since 2011. Having peaked at 2.9MMbpd in 1999, the UK oil production was assumed to enter a period of precipitated decline, especially so when its annual output started to plummet by some 0.2MMbpd per year in 2009-2011. It bottomed out in 2014 at 0.85MMbpd and thanks to a general oil price recovery and a rather successful cost-efficiency drive managed to get back on the growth trajectory.

Source: BP Statistical Survey 2019.

With estimated remaining reserves of some 2.5 Bbbls, almost four times less than what Norway is assumed to have in its Continental Shelf, there’s a natural limit to which UK firms can go. Nevertheless, they have been working hard – 2019 YTD has seen a monthly average of 11 development wells spudded per month, well ahead of the 2016-2018 period when the average was within the 6-8 wells per month interval. Most of the wells are located in West Shetlands and the Northern North Sea, an area that was deemed commercially unattractive due to deposits tilting towards the heavier side. These heavy fields, most notably the recently commissioned Equinor-operated Mariner field (15.2° API, 1.1 percent Sulphur), will be the new face of Britain’s oil industry in the 2020s.

Discovered in the 1970s and 1980s, Britain’s heavy oil was neglected due to their technological complexity (thus, cost inefficiency) and unfavorable pricing, with heavy crudes traded at substantial discounts to flagship grades like Brent or Forties. Yet developments in extraction technology and most importantly narrowing discounts on sweet heavy and medium heavy crudes (the Sulphur rarely goes above 1 percent in the Northern North Sea area) have made their advancement possible. There is just one blemish (albeit a quite significant one) to these heavy deposits – the best new fields that are commissioned wield reserves in 100-150 MMbbls interval, incomparable to the 5BBbls bounty of Forties.

All in all, thanks to its heavy oil deposits Britain can avail itself of another decade of relative output stability, with production hovering around the 1MMbpd mark for most of the upcoming five years. The post-2024 horizon augurs a gradual decline as minor discoveries fail to compensate for the dropping output of erstwhile giants. Increased rates of development drilling can help mitigate the steepness of the drop, yet it is unlikely that they might overturn the trend. Some help might come from weaker crude demand – in the past three years there was barely any change in refinery runs, yet with the proliferation of electric vehicles (some 800 000 EVs are expected to hit British roads in the upcoming 5 years) the ever-rising demand for Diesel fuel in the UK might finally come to an end and start declining.

Whilst UK oil prospects raise some long-term worries, its gas future is already a headache in the now. Britain’s shale reserves were for a long time considered to be the next thrust of UK oil and gas development. Britain’s onshore shale gas reserves were estimated at 1300 TCf, the overwhelming majority of which lay onshore. Yet similarly to many European countries, any development of shale projects was met with skepticism and disinclination by the populace. Contrary to countries in continental Europe though, the ruling Conservative Party was supportive of shale projects as it saw them as Britain’s most realistic claim to keep the country’s energy security afloat. Yet one blow after another has diminished the chances of British shale drillers, leaving them on the brink of a drilling ban.

It all started with Cuadrilla spudding the first-ever shale gas well in the United Kingdom in October 2018. Having fracked a mere 5 percent of the well, the UK firm was forced to stop drilling as its activities caused tremors in Preston New Road that exceeded the allowed 0.5 magnitude. It took almost a year to resume drilling this August, yet the optimism was soon curbed by a new report from the University of Nottinghamshire, claiming that Britain’s shale gas reserves six times smaller than previously expected (200 TCf) and that the previous estimates were made based on the findings of shale drillers in the United States and that the actual quality and quantity of UK shales was not properly appraised.

200 Trillion cubic feet would still cover roughly a decade of British gas demand, thus even this disconcerting development need not derail developers across the country. Yet then came the earthquakes again – well above the government’s 0.5 magnitude limit, attaining 1.5ML. Even though Cuadrilla likened the tremors’ impact to a shopping bag being dropped to the floor, it was forced to halt operations again. And here comes the difficult part (at least for Cuadrilla) – the shale driller’s drilling permit is valid only until November 2019 and it seems that persuading the populace of North Nottinghamshire that the tremors are insignificant will be close to impossible. If Cuadrilla cannot secure a license extension to continue with its drilling program from the local authorities, it would be forced to ask the Johnson government to nullify the decision and grant it the extension in a centralized manner.

The Johnson government has reiterated its support for shale gas drilling as recently as August, yet the consequences of Brexit might compel the government to drop the cause of shale gas altogether. First of all, shale gas development is wildly unpopular, and the increasing intensity of tremors did little to change people’s minds. Second, a group of 41 Conservative MPs has issued a manifesto this August, called to a nationwide ban of hydraulic fracturing. Such manifestos would look commonplace with Labour or SNP members of parliament (Jeremy Corbyn himself protested at Cuadrilla’s Preston New Road field) yet are a complete novelty within the Conservatives’ realm. Third, given that only two companies are currently working on shale projects (Cuadrilla and Ineos), no major business would be jeopardized by an outright ban.

Source: BP Statistical Survey 2019.

Although conventional gas fields bounced back in 2014-2018, too, they are poised to start their gradual decline sooner than oil, moving back to the average -3 percent per year-on-year change in 2008-2018. Gas reserves currently stand at 5.3TCf, eight times less than Norway. Moreover, the UK does not even have access to Barents Sea like Norway does to nourish hopes that a major discovery might be just around the corner. LNG imports have been increasing this year at a rapid rate and the January-October 2019 import volumes (9.4 million tons LNG) are already on par with the highest-ever annual rate set in 2015. In view of the above, what would post-Brexit UK hydrocarbon production look like? Declining production, heavier oil grades, no shale gas and increasing LNG imports – not a particularly appealing prospect.