Russia has never been producing more oil than it does now – up to the OPEC/OPEC+ production cut agreed upon in Vienna last week, almost every single month brought along production increments. The latest available official production data, for October 2018, shows that Russian output hiked to 11.412mbpd (the OPEC monthly report states an even higher number, 11.6mbpd, yet it is safer to rely on Russian data). Year-on-year this leaves Moscow with an almost 0.5mbpd increase, even compared to October 2016 - that particular month before the onset of OPEC+ production curbs when Russian producers squeezed out every molecule of oil they could to set up a high output basis – Russia produces 0.2mbpd more oil now than it did then.

Yet behind the success story, Russian geologists have voiced worries that the country needs to crank up its geologic exploration activities if it does not want to run out of crude in 35-40 years. As we have already established, Russia’s currently registered recoverable oil reserves would deplete themselves by 2045 (on the other hand, 2P gas reserves would be enough for some 160 years). Of course, this does not mean Russia would run out of oil – every year since 2006 Russia’s annual oil reserves’ increment has managed to stay above or roughly around the annual production volume. Thus, thanks to geological prospecting, the onset of Russian oil drought is always postponed a bit. Yet the overall trend is turning to negative – this year’s expected annual increment…

Russia has never been producing more oil than it does now – up to the OPEC/OPEC+ production cut agreed upon in Vienna last week, almost every single month brought along production increments. The latest available official production data, for October 2018, shows that Russian output hiked to 11.412mbpd (the OPEC monthly report states an even higher number, 11.6mbpd, yet it is safer to rely on Russian data). Year-on-year this leaves Moscow with an almost 0.5mbpd increase, even compared to October 2016 - that particular month before the onset of OPEC+ production curbs when Russian producers squeezed out every molecule of oil they could to set up a high output basis – Russia produces 0.2mbpd more oil now than it did then.

Yet behind the success story, Russian geologists have voiced worries that the country needs to crank up its geologic exploration activities if it does not want to run out of crude in 35-40 years. As we have already established, Russia’s currently registered recoverable oil reserves would deplete themselves by 2045 (on the other hand, 2P gas reserves would be enough for some 160 years). Of course, this does not mean Russia would run out of oil – every year since 2006 Russia’s annual oil reserves’ increment has managed to stay above or roughly around the annual production volume. Thus, thanks to geological prospecting, the onset of Russian oil drought is always postponed a bit. Yet the overall trend is turning to negative – this year’s expected annual increment vs production percentage is most likely to end up below 100 percent by a narrow margin (see Graph 1).

Graph 1. Russian Oil Reserves Annual Increment vs Production 2007-2018 (mtpa).

'

'

(Click to enlarge)

Source: Russian Ministry of Energy, Russian Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment.

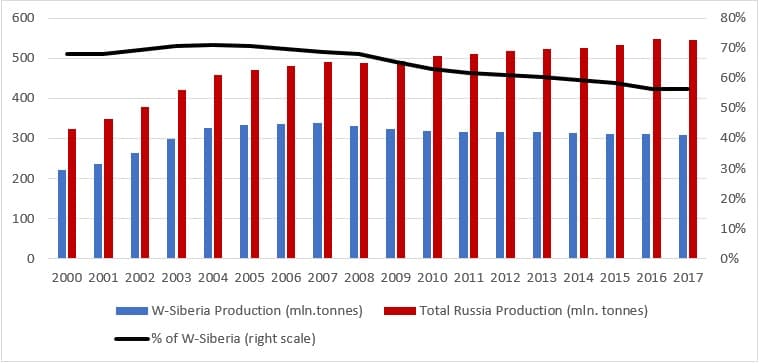

Rosgeologiya, the state-owned leader on the Russian prospecting market, has indicated that the risk seeing Western Siberian production volumes halve in 15-20 years is still of current concern. A decline in W-Siberian output was on cards for some time already – initially expected in late 1990s, it was then foreordained for mid-2000s. Now it seems that the year 2007 will mark the highest W-Siberian volume produced in modern Russian history, hitting 338 million tons (see Graph 2) – it has been an uninterrupted, albeit very slow, decline every since. What is remarkable about this is that W-Siberia still accounts for 60 percent of Russia’s 3P oil reserves (totalling 29.7 billion tons), meaning the oil is still there but needs special conditions to be produced. But how?

Graph 2. Western Siberian Production’s Share in Total Russian Production 2000-2017.

(Click to enlarge)

Source: Russian Ministry of Energy.

Interestingly, in the long term the Russian government expects crude production to grow, whilst exports are to stay at the same level as currently – its latest long-term forecast stipulates 252 million tons of exports in 2036 (256 million tons last year). Crude production is expected to grow annually by 0.2 percent in 2019-2024, then contract every year by 0.1 percent in 2025-2030 and remain flat in 2031-2036. This would mean Russian oil output to be around 557 mtpa in 2036 - as per the assumptions of Ministry of Economic Development, against the background of flat exports the surplus would go to Russia’s refineries, which by that time are expected to reach a new level of sophistication, especially the ones in the Southern part of „European” Russia and Eastern Siberia.

But all government reports and forecasts go remarkably vague on how to achieve this given the relatively mature condition of Russia’s oilfields. They usually state that in order to keep up the production levels, further exploration drilling and production enhancement solutions are needed. This is a massive understatement. After the universal crash of the 1990s, Russian oil companies did a really good job in ramping up development drilling rates all over the country. In fact, the 2017 level of 27 648 km drilled (see Graph 3) is surpassed by only 6 years in the last century and it is not that far off from the all-time record of 40 600 km, evidenced in 1987. Prospect drilling, on the other hand, is a bleak reflection of Soviet-era activity, roughly 8 times lower than the 1987 record of 8 400 km drilled.

Graph 3. Russia’s Development vs Prospect Drilling in 2000-2018.

(Click to enlarge)

Source: Russian Ministry of Energy.

Prospect drilling is expected to increase 4.5 percent year-on-year, at 993-995km getting very close to the 1000km threshold which was last surpassed seventeen years ago. Looking at Graph 3, one can see that unquestionably there is progress, apart from two shock years (2009 and 2015) when expenses were cut on everything imaginable, the black line edges higher and higher with time. The problem is the extent of the hikes – if it wants to get all its ducks in a row to confront future production decline problems, it cannot afford annual 30-40km increases in prospect drilling rates. All the major greenfield development of the last three years – the Russkoye field (oil reserves of 420 million tons), Tagulskoye (286 million tons), Suzunskoye (57 million tons) or Kuyumbinskoye (281 million tons) were discovered in 1968, 1988, 1972 and 1974, respectively.

The sad truth is that Russia cannot freeride on its Soviet heritage forever. In fact, throughout the first 18 years of the 21st century, only two discovered oilfields contain more than 100 million tons – Savostyanovskoye (160 million tons) and Pobeda in the Kara Sea (130 million tons). The dwarfing of Russian discoveries can be eloquently illustrated with last year’s harvest – the biggest oilfield discovered was the Sudbadarovskoye field, with recoverable reserves of 16 million tons. 95 percent of oil-containing field that are still not allocated and remain under the control of the Ministry of Natural Resources are classified as „small” (1-10 million tons of reserves) and „very small” (less than 1 million tons). The only unallocated field in the state’s subsoil reserve fund to contain more than 20 million tons – the Rostovtsevskoye field with reserves of 30.2 million tons – will most likely never be handed out as it is located on the territory of a Yamal peninsula nature reserve.

Oddly enough, developments in Russia’s oil sector are anything but reflected in its gas sector, in which genuinely large discoveries are reported on a quarterly basis. Just two weeks ago, NOVATEK reported a 2.3 TCf Nyakhartinskoye discovery, located around the Taz river estuary in Western Siberia. Thus, for oil to be sustainable in the long term there are only two ways out – either companies step up their investments in prospect drilling or it is the state that returns to Soviet-era levels of drilling activity (it then allocated the discovered fields by means of auctioning). In a country like Russia, the latter seems more preferable – it secures a stream of income for the state, all the while making sure that companies continue to produce in Russia (and do not move to the Middle East to keep their output commitments).

Yet the Russian government seems to be moving in the other direction. In 2017, on the back of fiscal constraints, it has sequestered Rosgeologia’s resource base replenishment programme by 25 percent (from 40 billion RUB to 30 billion RUB) and intends to keep it at the same level throughout 2019-2020. Simultaneously, it seems intent on giving out flank parts of already allocated acreages, which would benefit the top majors. As usual, one of the largest opponents of providing Rosgeologia with sufficient financing is Rosneft, intent on concentrating as much power in its hands as possible, especially when it comes to the Arctic shelf, pretty much the only part of Russia where discoveries could be easy to achieve, provided they can secure the required financing. The government has called for an inventory count of Russia’s oilfields (to determine which fields should be supported by tax breaks) – only another bout of temporizing after years of doing the same.

'

'