A couple of late Friday tweets have managed to avert an event that would have caused a great amount of distress to the US refining industry – the imposition of tariffs on all goods imported from Mexico. In a fast-moving negotiation scuffle, President Trump first announced the levy of sanction on May 30, only to have them „indefinitely suspended” having received guarantees from Mexico on tightening the southern border security. Although it is true that the oil sector would not have been the biggest victim of the potential tariffs, automobiles and agriculture would suffer more, the eschewal of escalation saved US refiners from direct multi-million losses and severe sourcing problems.

One could hear a unified sigh of relief when the tariffs were called off. Implemented under the International Emergency Powers Act of 1977, the tariff plan would have seen the first 5 percent levied on June 10, 2019, with additional 5-percent hikes slapped on Mexico for every month in which the Mexican authorities fail to stop the wave of migrants towards the United States. The ultimate threshold was set at 25 percent (for all goods, services are not subject to sanctions). As we will see further on, the White House need not even go the full way in sanctioning Mexico to render US-Mexico crude trade economically unviable, even a 10-15 percent hike would be enough to do that. Yet the underlying truth is that was Mexico to be sanctioned, there is no one to replace it with.

1. US Gulf Coast…

A couple of late Friday tweets have managed to avert an event that would have caused a great amount of distress to the US refining industry – the imposition of tariffs on all goods imported from Mexico. In a fast-moving negotiation scuffle, President Trump first announced the levy of sanction on May 30, only to have them „indefinitely suspended” having received guarantees from Mexico on tightening the southern border security. Although it is true that the oil sector would not have been the biggest victim of the potential tariffs, automobiles and agriculture would suffer more, the eschewal of escalation saved US refiners from direct multi-million losses and severe sourcing problems.

One could hear a unified sigh of relief when the tariffs were called off. Implemented under the International Emergency Powers Act of 1977, the tariff plan would have seen the first 5 percent levied on June 10, 2019, with additional 5-percent hikes slapped on Mexico for every month in which the Mexican authorities fail to stop the wave of migrants towards the United States. The ultimate threshold was set at 25 percent (for all goods, services are not subject to sanctions). As we will see further on, the White House need not even go the full way in sanctioning Mexico to render US-Mexico crude trade economically unviable, even a 10-15 percent hike would be enough to do that. Yet the underlying truth is that was Mexico to be sanctioned, there is no one to replace it with.

1. US Gulf Coast Refiners Need Heavy Crude

Of the 3.7mbpd crude Texas refineries imported in March 2019 (the last month for which official data were available at the time of this writing), 98 percent were heavy barrels. Mexico is the top seaborne supplier of heavy barrels to the United States, in fact it exports more than double than its closest contender Colombia. With Venezuela now degradated to a second-tier crude exporter, the exports of Maya (21-22° API, 3.5 percent Sulphur content) currently make up approximately 15 percent of global heavy crude trade.

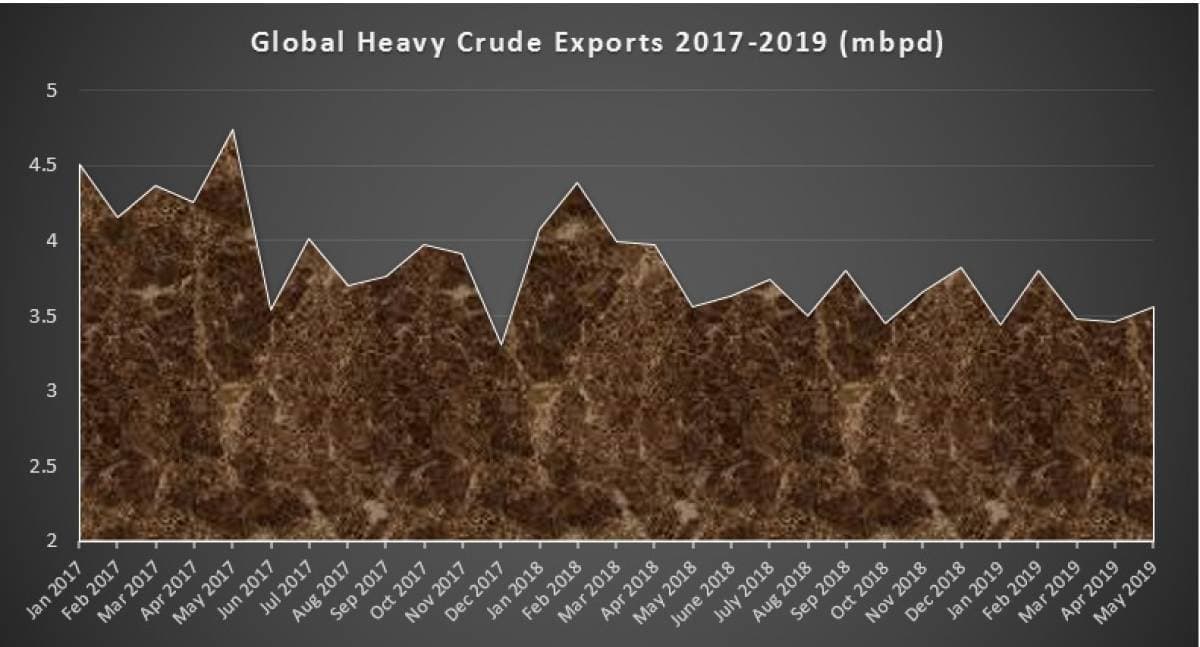

From this one can easily deduct that any disruptions in Maya supply would not only compel US refiners to go for sub-optimal solutions as there is not enough heavy production worldwide but also see heavy crude prices skyrocket into previously unseen heights. Aggregate heavy crude exports, i.e. comprising all seaborne grades whose density is below 25 degrees API, have dropped almost 0.5 mbpd year-on-year and more than 1mbpd compared to May 2017. India and China alone account for one-third of global heavy demand and are willing to pay the extra premium if need be, placing US refiners in a difficult situation were they to search for alternative heavy streams, all the more so as the remaining ones are substantially farther off than Mexico.

This is further accentuated by the fact that whatever new production emerges in the United States, it is most likely a very light and sweet resource. Almost 60 percent of all new Permian Basin production was within the 40-45 API degree interval, with a further 13 and 8 percent in the 45-50 and 50-55 API slate. This has had some consequences in the crude market – take the creation of a new US crude stream, West Texas Light (WTL) – yet it will impact product markets even more substantially. The lighter the American crude output, the bigger the problem for refiners as they run the risk of facing oversupply in the naphtha segment, potentially even the gasoline one, to the detriment of heavier yields.

2. US Gulf Coast Refiners Need Mexican Crude

In view of the data above, one has to highlight the crucial role Mexican crude is playing in keeping normal refining operations afloat in times of sanctioned Venezuelan supply and dropping Colombian output volumes. If the first 5-percent tariff hike would take place, Mexico’s flagship crude grade Maya would appreciate 2.5-3 USD per barrel for American refiners – were this to happen under current circumstances, the USGC coking margins would fall to 5 USD per barrel. The introduction of a 10-percent tariff would already raise the question of financial profitability, whilst a 15-percent tariff rate would eliminate any doubts on the impossibility of buying Mexican crude.

Let’s just take US Maya imports for one specific month. In May 2019, US refiners took in 24.8 million barrels of Maya (equivalent to 810kbpd), meaning that merely the first tariff rate of 5 percent would result in monthly $80-85 million losses for them. In a hypothetical case that the tariffs are hiked to 25 percent and US refiners keep on buying Maya crude, the monthly loss rate would be in the $400-420 million range. Without even adding Isthmus and Olmeca imports to the US, one can get a clear understanding of what guided US refiners in their vocal non-admission of the tariff plan. That is not to account for the fact that now it would not seem very politic to jeopardize the „new NAFTA” trade agreement, the US-Mexico-Canada Trade Agreement (USMCA), at a time when a lot of political capital has been invested into it and it was just freshly submitted to the US Congress.

3. Mexico Needs a Period of Calm to Sort Itself Out

All the tariff-slapping flareup came at one of the worst possible moments for Mexico. It might be argued that it tried to halt the migrant flow to the best of its capacities – April 2019 saw the highest number of entry denials and apprehensions (almost 100 000 in just one month) in the whole of this decade – yet due to the scarcity of available resources and its unwillingness to antagonize Central American nations it could only do so much. The administration of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO) is struggling to render the national oil company PEMEX lean and efficient, reshaping it so that it no longer remains the world’s most indebted oil company.

The country being Mexico (and not Switzerland), there has been little progress so far – in fact, the tariff mayhem happened concurrently with Fitch and Moody’s cutting Mexico’s credit rating, arguing that the government-sponsored bailout of PEMEX will jeopardize Mexico’s own economic outlook. With this being said, one has to point out that the bailout package is generally perceived as sub-optimal, despite taking up 0.2 percent of Mexico’s GDP, and apparently a lot more money is needed to save the sinking giant. Although it is true that tariffs might raise the price of Mexican crude globally, it would be counterintuitive for AMLO to seek them as they would weaken the Mexican state, the ultimate savior of PEMEX.

Needless to say, there still persists a risk of a deterioration in US-Mexico political ties and the tariff threat might be raised once again. Now, too many factors converged to tilt the balance towards pacification, yet the future might hold for us another escalation of tensions. In case tariffs are back on the agenda, Mexico has little space to retaliate – it cannot sanction natural gas and light US crude imports as it needs them for industrial power generation and crude dilution, respectively.