It is genuinely difficult to predict what the Iran conundrum would lead to in the end, however, the current setup appears to be a very sophisticated collision course. Quite remarkably, Tehran has not made recourse to provocations in the Hormuz Strait, despite all the previous tough talk and, it seems, would not be discomfited if a final diplomatic solution would be hammered out. The US sanctions have hurt the Iranian economy and its energy sector, yet due to the introduction of waivers to eight carefully chosen nations the impact was partially mitigated. The next calibrated blow to Iran will be designed to do even more economic harm, however, would still not be enough to bring about the oft-professed goal of US foreign policy – bringing Iranian crude export to naught.

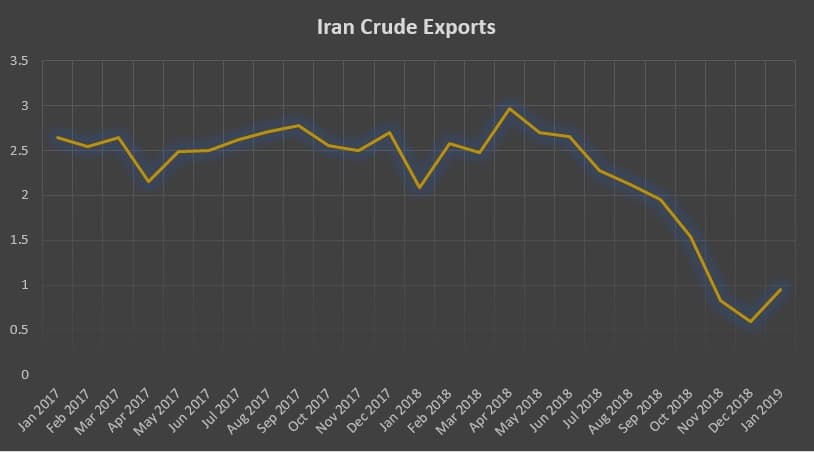

Three full months into the sanctions period, one can surely state that Iranian production plummeted by 1mpbd within six months. By December 2018 already, crude output dropped to 2.75mbpd and has stayed around that level since. In this respect, it has to be pointed out that since October 2018 Iran has stopped informing OPEC about its current monthly production estimates, however, the OPEC data based on secondary sources has been quite accurate, thus allowing us to assess the scope of the reduction. The 1mbpd production decline did not result in Iran lacking in crude – in fact, exports have shrunk even more steeply, by some 1.5mbpd since May 2018 when the November 04 sanctions deadline was first put forward.

Source:…

It is genuinely difficult to predict what the Iran conundrum would lead to in the end, however, the current setup appears to be a very sophisticated collision course. Quite remarkably, Tehran has not made recourse to provocations in the Hormuz Strait, despite all the previous tough talk and, it seems, would not be discomfited if a final diplomatic solution would be hammered out. The US sanctions have hurt the Iranian economy and its energy sector, yet due to the introduction of waivers to eight carefully chosen nations the impact was partially mitigated. The next calibrated blow to Iran will be designed to do even more economic harm, however, would still not be enough to bring about the oft-professed goal of US foreign policy – bringing Iranian crude export to naught.

Three full months into the sanctions period, one can surely state that Iranian production plummeted by 1mpbd within six months. By December 2018 already, crude output dropped to 2.75mbpd and has stayed around that level since. In this respect, it has to be pointed out that since October 2018 Iran has stopped informing OPEC about its current monthly production estimates, however, the OPEC data based on secondary sources has been quite accurate, thus allowing us to assess the scope of the reduction. The 1mbpd production decline did not result in Iran lacking in crude – in fact, exports have shrunk even more steeply, by some 1.5mbpd since May 2018 when the November 04 sanctions deadline was first put forward.

Source: OPEC.

The US State Department officially states that there has been no decision on the prolongation of the waivers and that even though it does not want to extend the exemptions to China, India, Turkey, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Greece and Italy, it will base its final decision upon an assessment of how viable it would be to replace Iranian crude volumes. In diplomatic doublethink, this might be translated as “we will extend the waivers, but not for everyone”, which is very much in line with what the oil market generally expects. There are some evident truths which intimate future US steps – like the one that Taiwan, Greece and Italy have not bought a single Iranian cargo since the onset of sanctions and are most likely to be out of the waivers game following May 05.

Source: OilPrice data.

Difficult as it is to assess Iran’s crude exports following November 2018 (a lot of oil went into floating storage before it and was gradually supplied to Asian markets, especially China), currently the monthly average hovers around 1-1.1mbpd. This is mostly going to three countries – China, India and Turkey, in that order of significance, even though the internal dynamics are all different.

China started out strongly by buying 13MMbbl in November, followed through with 6MMbbl in December and 4MMbbl in January, with seemingly no crude being exported to China whatsoever during February. India is the most predictably behaving entity - it has bought 10MMbbl in November, 6MMBbl in December and 7MMbbl in January, mostly sending the crude to New Mangalore, Paradip and Vadinar. Turkey started buying in December and buys an average 2MMbbl per month, mostly sailing to the state oil company TUPRAS to Tutunciftlik. The two East Asian economic powerhouses to be granted a waivers, South Korea and Japan, have only started buying Iranian crude in 2019, rendering the Iranian crude export dynamics tricky to read.

South Korea is currently the hottest market destination for Iranian crude, with 4 Iranian VLCCs en route to the port of Daesan, bringing roughly 6.5 MMbbl of crude (aboard MTs Sonia I, Dorena, Seastar II and Deep Sea) to the Asian country which didn’t buy any Iranian oil between November 2018-January 2019. The first Japanese arrival took place just a couple of days ago when MT Kisogawa reached the Chiba port on the interior of Tokyo Bay. Another 2 MMbbl-carrying VLCC, MT Tsugaru, is on its way to Japan and is expected to discharge at the port of Kawasaki on February 22. India and China each have one ship currently sailing – MT Hasna destined for New Mangalore and MT Dan destined to an unknown location in China – both carrying 2MMbbl of crude.

It seems that Iraq has been demonstrating more courage in the face of potential US sanctions than any other country. Baghdad and Tehran have ironed out a new payment mechanism that would allow Iraq to pay for electricity and gas it imports from Iran, and brought it to life during last week’s Baghdad visit of Iranian central bank governor Abdulnasr Hemmati. The new mechanism, already operational, would revolve around Iran setting up an Iraqi Dinar and an EURO denominated account in an Iraqi bank, which will then be used to settle all of Iraq’s debt (which, as of early February 2019, is estimated to amount to $2 billion). The 45-day waiver granted by the US Administration to Baghdad to continue Iranian imports runs out on March 18, however, is widely expected to be prolonged as no one would like to see the August-September Basrah protests repeated.

In light of the above, the European reaction to the US sanctions is somewhat reproachable. Whilst publicly stating to preserve the Iran nuclear deal and to facilitate trade with Iran, the long-mooted special purpose vehicle turned out to be remarkably wishy-washy. INSTEX, short for an Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges as the SPV is officially labelled, will only focus on pharmaceuticals, medical devices and agricultural goods, which were not subject to US sanctions anyway. Moreover, the pharmaceutical and medical export-import ratio is heavily tilted in Europe’s favor (roughly 1:30 in terms of value), so it is more of a sales promotion than a real concern for Iranian customers. Although it is fair to say that humanitarian trade does suffer from the oil-related sanctions, especially in terms of insurance coverage and shipping, yet it would be nice to see what can the EU propose with regard to crude trades.

Tehran tries to be ingenious in circumventing the US sanctions, to varying levels of success. Its attempt to market Iranian crude on the domestic energy exchange (IRENEX) has gone largely unnoticed. Following three crude tenders, NIOC now intends to sell the condensate in 35kbbl lots (at a fixed price of 61.04 USD per barrel) to private consumers or traders, who would then have to find a suitable market for it, either at home or abroad. During the first two crude trading sessions, NIOC sold 0.98 MMbbl of crude, however the third trading session, held on January 21, yielded no interest in the volumes (despite the advantageous fixed price of 52.42 USD per barrel and a very favorable 90-day settlement period). It remains to be seen whether condensate trade would fare any better.

Thus far developments around the Iranian sanctions have confirmed Tehran’s fears – China, hitherto expected to provide a safe lifeline to Iran, is gradually losing interest; Europe, which has promised not to give up on Iran and the nuclear deal, seems fully cognizant (and tacitly disenchanted) over the lengths it can go vis-à-vis a unilateral US sanctions levy. India, the only country to have implemented a fully operational trade mechanism denominated in rupees, is lobbying hard to keep on importing Iranian crude, however, its geopolitical clout is inadequate to persuade the White House. Iraq is playing its game right to maintain energy ties to Iran, however, unfortunately for Tehran they are interested in gas and electricity imports, not crude.

The US slapping sanctions on Venezuela will definitely come in handy for Iran, in its quest to wipe off further (heavy) volumes of crude Washington faces a risk of a steep price hike, something which is much more effective in fending off its aggressive foreign policy than the arguments of Indian, Chinese or Turkish officials. Against this background, it remains to be seen whether Iran would not escalate the situation by threatening to leave the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), yet even if it does, it is not going to change much. Europe does not matter anymore, the parley is to be held with the United States.