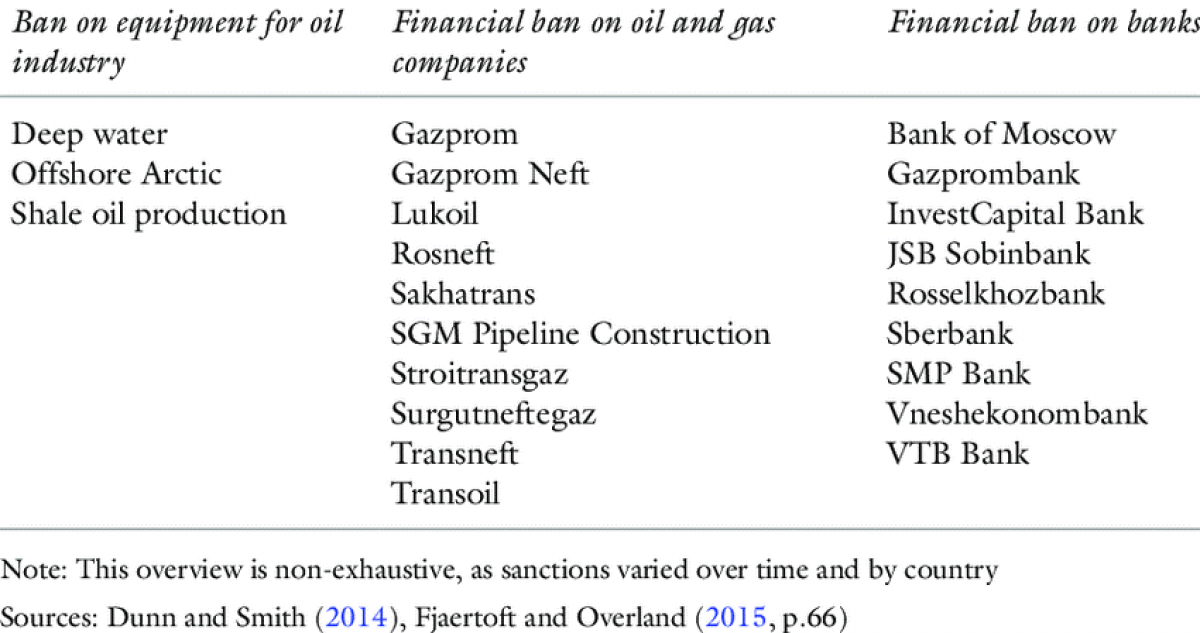

With the sanctioning and tariff-slapping frenzy capturing most of media attention nowadays, we should get ready for a new epoch of geopolitics where the World Trade Organization’s standard rules are no longer the negotiator’s handbook. This also means that oil and gas investments and trade will be subjected to a whole new array of restrictions, making the navigation of tumultuous markets ever more difficult. Yet sanctions are proposed, written and amended by people, paving the way for straight-out errors, omissions and loose ends which the oil trading community must seek to exploit if it wishes to stay independent of political pressurizing. The US sanctions on Russia provide an illustrative case.

The US sanctions against Russia prohibit investment in Russia’s deepwater, Arctic offshore and shale oil, without any additional explanations on the actual classification parameters of shale – roughly put, they ban shale without saying what shale is. And herein lies a great opportunity and also a great, perhaps intentional, omission on the part of the US executive power at that point (the sanctions were introduced in 2014 by the Obama Administration). Shale oil in its strictest designation means kerogen oil, i.e. oil extracted from oil shales by means of artificially heating it up, which has been present in Estonia and Brazil for several decades already. But that is not shale as we know it – so let’s better examine the interpretation of another generally accepted term, tight…

With the sanctioning and tariff-slapping frenzy capturing most of media attention nowadays, we should get ready for a new epoch of geopolitics where the World Trade Organization’s standard rules are no longer the negotiator’s handbook. This also means that oil and gas investments and trade will be subjected to a whole new array of restrictions, making the navigation of tumultuous markets ever more difficult. Yet sanctions are proposed, written and amended by people, paving the way for straight-out errors, omissions and loose ends which the oil trading community must seek to exploit if it wishes to stay independent of political pressurizing. The US sanctions on Russia provide an illustrative case.

The US sanctions against Russia prohibit investment in Russia’s deepwater, Arctic offshore and shale oil, without any additional explanations on the actual classification parameters of shale – roughly put, they ban shale without saying what shale is. And herein lies a great opportunity and also a great, perhaps intentional, omission on the part of the US executive power at that point (the sanctions were introduced in 2014 by the Obama Administration). Shale oil in its strictest designation means kerogen oil, i.e. oil extracted from oil shales by means of artificially heating it up, which has been present in Estonia and Brazil for several decades already. But that is not shale as we know it – so let’s better examine the interpretation of another generally accepted term, tight oil.

Tight oil is what the Obama Administration presumably wanted to ban – it is just that the analogy with shale gas has somewhat confused the Bureau of Industry and Security staff responsible for drafting the sanctions bill. The November 2014 OFAC issued a clarification on the issue, which brought us just a tiny bit further, stipulating that “shale applies to projects that have the potential to produce oil from resources located in shale formations”. However, the phrasing of the sanctions bill implies that if the recoverable oil has already migrated out of the shale source rock, it should be perfectly legal for anyone willing to invest in such projects in Russia to do it.

As any seasoned Russia watcher would confirm, one can see only a handful of projects when Western majors went forward with projects susceptible to sanctions and penalties. Yet that is not because the sanctions restrict them outright in doing so, rather it is out of fear of US retaliation which would go beyond the immediate content of the sanctioning bills. This is further corroborated by the fact that the transfer of technologies which should be legal in any case – for instance, the multi-faceted expertise of US companies in multistage fracturing and horizontal drilling – has never appeared on the US-Russia agenda again.

A number of analysts has pointed out that US Bakken production combines the two key elements here – oil migrating from the shale source rock (namely, from the Upper and Lower Bakken to the non-shale Middle Bakken) and a plentiful usage of multistage fracturing and horizontal drilling due to a low-porosity and low-permeability quality. Guess what, there is a Bakken lookalike in Russia and by a strange twist of fate it is Russia’s largest shale deposit of all, the Bazhenov Suite. The Bazhenov Suite is estimated to contain more than 1.2 trillion barrels of crude, yet very low extraction rates (5-7 percent) and no clear understanding what combination of drilling technologies would be best suited to extract the hydrocarbons has hindered its boom.

It is still rather poorly mapped in general (seismic surveys are of little use as the thickness of the carbonated and sand layers is usually smaller than seismic resolution itself) yet it is almost certain that parts of the Bazhenov would be perfectly suitable for non-sanctionable development (with the obvious caveat that this is right unless sanctions get extended even further).

Now here comes the most interesting part – some European oil majors have not stopped their shale projects in Russia, availing themselves of the opportunities the current phrasing of US/EU sanctions present. Thus, when Equinor signed up for the development of the Severo-Komsomolskoye field it could easily argue that it was aiming for tight oil and not shale – something that American companies might do as well were it not for potential ramifications on the political side. The Severo-Komsomolskoye field is currently the largest known deposit of high-viscosity crude in the whole of Eurasia, with estimated recoverable oil reserves currently standing at 203 million tons (in addition to the 5.7 TCf of gas reserves).

The Severo-Komsomolskoye field has been producing gas from the early 1990s yet because of the difficult working conditions in the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Region – permafrost and omnipresent marshlands – it only started producing in 2016. The development of the field augured the implementation of new approaches and technologies, for instance, it witnessed the first open-hole gravel packing well completion in all continental Russia. Equinor concurrently develops projects in Russia’s second-most promising unconventional region, the Domanik formation in the Volga-Urals Region. As Reuters reporters pointed out, right until 2014 Equinor labelled its Domanik projects “shale” and only after the imposition of sanctions moved to denominate them as “limestone” ones.

Source: USGS.

Technically, the latter is correct as drilling focuses on the cherty limestone deposits of the Domanik formation and hence should not be subject to US or EU sanctions. Before spudding the first exploration well there in 2017, Equinor made sure to doublecheck the EU’s interpretation of its own Russia sanctions so as to avoid future legal clashes. This might provide a very handy advantage for European majors participating in Russia’s tight oil romance – as opposed to ExxonMobil or ENI who have invested into deepwater projects in the Black and Kara Seas, Equinor and BP are now by far the most advanced Western majors on Russian territory. Moreover, tight oil projects (or “hard-to-recover” ones as the Russian denomination goes) are under a zero rate of mineral extraction tax, which makes their development all the more enticing.

The Russian tight oil game is still far from being won - the stakeholders still have to sort out all the technological solutions required and finding a tailor-made solution for tight oil development in permafrost conditions amid a vast marshland, thus bringing down production costs from triple-digit numbers. Yet the willingness to invest and work there also point out the necessity to take measured risks in times when politicians want to impede long-term business cooperation for short-term PR benefits. As the Russian shale/tight oil story proves, sanctions are only as good as the people who write them. Banning all forms of cooperation borders on the impossible, therefore it is our common task to find new forms and ways of business even when the conditions are largely unfavorable.