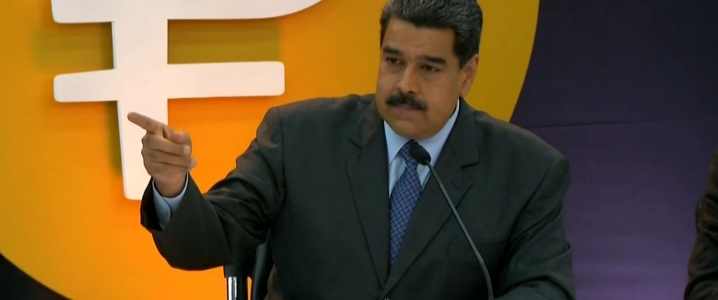

Ambivalent is the word that best describes the condition Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro has found himself in. From a formal point of view, his January 10 reinauguration went along smoothly and oil production, the backbone of Venezuelan economy, has managed to bounce back somewhat from the trough it has found itself this autumn. Yet if you look closely, navigating through 2019 might turn out to be even more difficult for the Bolivarian leader than surviving the arduous year of 2018. International pressure is mounting, including Caribbean countries that thusfar have been either supportive or neutral towards the Venezuelan political leadership, all the while PDVSA still struggles to become a „normal” national oil company.

But first let’s talk a bit about Venezuela’s success stories. After the steady declines in oil output witnessed in the first half of 2018, plummeting from 1.65 mbpd in January to 1.25 mbpd, production has stabilized somewhat around 1.15mbpd mark. PDVSA attributes this to the improved functioning of the three upgraders operating in the country, used for creating synthetic export grades out of the bitumenous 8-10° API crudes that the Orinoco Belt yields. The now-working crude upgraders are inevitably linked to foreign oil majors – PetroMonagas is developed with Rosneft, PetroPiar with Chevron, PetroCedeno with Total and Equinor – as the fourth upgrader, fully owned by PDVSA, has been out of operation for quite some time already.

Source:…

Ambivalent is the word that best describes the condition Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro has found himself in. From a formal point of view, his January 10 reinauguration went along smoothly and oil production, the backbone of Venezuelan economy, has managed to bounce back somewhat from the trough it has found itself this autumn. Yet if you look closely, navigating through 2019 might turn out to be even more difficult for the Bolivarian leader than surviving the arduous year of 2018. International pressure is mounting, including Caribbean countries that thusfar have been either supportive or neutral towards the Venezuelan political leadership, all the while PDVSA still struggles to become a „normal” national oil company.

But first let’s talk a bit about Venezuela’s success stories. After the steady declines in oil output witnessed in the first half of 2018, plummeting from 1.65 mbpd in January to 1.25 mbpd, production has stabilized somewhat around 1.15mbpd mark. PDVSA attributes this to the improved functioning of the three upgraders operating in the country, used for creating synthetic export grades out of the bitumenous 8-10° API crudes that the Orinoco Belt yields. The now-working crude upgraders are inevitably linked to foreign oil majors – PetroMonagas is developed with Rosneft, PetroPiar with Chevron, PetroCedeno with Total and Equinor – as the fourth upgrader, fully owned by PDVSA, has been out of operation for quite some time already.

Source: OilPrice data, OPEC.

Venezuela’s stature improved on the export side, too. When we last briefed you on the plight of the Venezuelan oilmen, the José terminal was operating at half-steam after a Greek tanker rammed into the wharf. By December 2018 the 950kbpd José terminal was back to full loading capacity, yet problems did not stop for PDVSA – criminal gangs are roaming around it freely in the hope of extorting money from sailors and stealing anything deemed valuable, especially at nights when the National Guard seems to be less vigilant. Despite all this, crude exports improved somewhat and ended the calendar year at the level of 1.4mbpd, roughly bringing the nation back to where it stood in June 2018.

President Maduro might cope with this, one would think, he has already survived much worse. That is true, however, international pressure against Maduro personally and the crumbling Venezuelan regime in general is not going to ease in the upcoming months, on the contrary. More than 60 countries have refused to recognize Maduro’s re-inauguration, and as a U.S. or Canadian denial was very much expected, former Caribbean allies like the Dominican Republic or Jamaica turning against Caracas comes as a definite surprise. On the day of Maduro’s reinstatement, the U.S.-based Organization of American States (OAS) passed a resolution, presented by steadfast U.S. ally Colombia, calling for the immediate invalidation of President Maduro. Guyana, Mexico, Jamaica, the Dominican Republic all cast an affirmative vote.

One can understand Guyana – Maduro stepped up the long-time Venezuelan claim that the Guyanese offshore should in fact belong to Caracas as part of the Guayana Essequiba, harassing ships conducting seismic surveying of it as recently as this December (then a Norwegian vessel contracted by ExxonMobil sailed away to avoid conflict). Jamaica is a more nuanced matter, though, as PDVSA owned 49 percent of the island’s only refinery, PetroJam. For years, the Venezuelan firm promised to upgrade the 36kbpd refinery into a full-conversion plant, yet the pledges never materialized and now the Jamaican government is intent to buy out PDVSA’s stake for a reported $280 million. A very similar story unravels with the Dominican Republic where vows to upgrade the 34kbpd RefiDomsa refinery, co-owned by PDVSA, ran aground amidst liquidity issues and prioritization of other projects.

Venezuela is poised to get rid of another part of its Bolivarian legacy, the 335kbpd Isla refinery located on the island of Curacao. Its lease ends in 2019 and PDVSA has already agreed to pass the baton to the Saudi-owned Motiva Enterprises. PDVSA stated it no longer needs the refinery but would like to utilize the storage facilities of Bullen Bay, as well as leased storage sites on the Dutch islands of Saint Eustatius and Aruba. These all have the incontestable advantage that they are not owned by PDVSA, hence cannot be seized as part of the myriad lawsuits that haunt Venezuela. Thus, Venezuela’s list of friends is getting thinner by the day, only Cuba (which receives 40-50kbpd of crude virtually for free) sustains some sort of solidarity spirit.

Thus, the Venezuelan political class has decided to prioritize upstream over downstream – even if all of Venezuela’s refineries crumble under the weight of the economic travails, imported naphtha would still be enough to maintain a stream of synthetic crude. It might be a feasible way out, however, the current head of PDVSA, brigadier general Manuel Quevedo, the first militaryman in charge of the national oil company in Venezuela’s recent history, might be already dismissed by then. All things considered, his 13-month tenure has been disastrous – oil production has fallen by some 0.6mbpd, fuel shortages plague the country and PDVSA is now fighting for the physical security of its upstream, midstream and downstream assets. It has to be said, though, that given the entrenched character of Venezuela’s problems, no one would be capable of digging PDVSA out of the monstrous hole it has been sinking into.

Venezuela’s problem is that personalities do not matter. Were Manuel Quevedo to be swapped for Jorge Rodriguez or Guillermo Blanco Acosta, the current communication minister and PDVSA vice-president for refining, nothing would change. President Maduro would continue to claim that Venezuela would ramp up oil production to 2.5mbpd in 2019 and climb ever-higher by reaching a 5mbpd production level by 2022, despite ample evidence that this year will most likely see another contraction. Venezuelan annual oil production averaged 1.33mbpd in 2018, a 0.64mpbd decline year-on-year and is expected to drop to 1-1.1mbpd in 2019. And this is still fused with a bit optimism. The U.S. Energy Information Administration wields the most pessimistic of all estimates, claiming Venezuelan output is in its death throes and will drop to some 0.7mbpd in 2020.

Source: OilPrice data.

In many ways, the future of Venezuela depends on U.S. foreign policy decisions. Would it support the parallel government that is springing up under the leadership of the 35-year old Juan Guaidó? If so, would it ban Venezuelan oil imports, either by designing the country as a state sponsor of terrorism or by banning outright deals with PDVSA? Although average annual Venezuelan crude exports to the United States in 2018 have fallen to a 30-year low of 0.49mbpd, America remains the largest market outlet for its crude. And it’s not just Citgo taking it in, Valero and Chevron are refining it, too. Moreover, U.S. exports seem to have overcome a freefall in early 2018 and show less signs of month-on-month volatility. Thus, business interests run counter to the volition of a rather pugnacious White House administration. We will keep a close eye on how the situation in Venezuela unfolds.