Roughly a year and half ago, US President Donald Trump has called on Qatar to stop the funding of terrorism and the spread of its “extremist ideology”, claiming that the nation of Qatar “has historically been a funder of terrorism at a very high level”. This came about while Saudi Arabia and its Gulf allies initiated a joint campaign to isolate Qatar, which eventually proved completely ineffective. Not even six months later, Qatari Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al Thani was once again sitting next to the US President, who labelled him a “friend of his” and a helpful force in fighting terrorism. In a densely interwoven development of events, Qatar did in fact manage to find an elegant way out of a situation which once seemed insolvable.

Now fast-forward into present-day America, which abounds in Qatari investment in oil and gas projects – some of them are already known, some will emerge with time. First the Qatari Sheikh promises investments into US oil and gas, both conventional and unconventional, then the contours of Qatar operating an LNG terminal in Texas emerges and Doha pledging to invest to the order of $20 billion in US energy. The drift towards the United States serves a double purpose – it changes attitudes towards Qatar, easing the international pressure on the Middle Eastern nation (just as Rex Tillerson would have urged), whilst also diversifying Qatar away from Europe and the Middle East and making sure the impending US LNG wave will happen to the financial benefit…

Roughly a year and half ago, US President Donald Trump has called on Qatar to stop the funding of terrorism and the spread of its “extremist ideology”, claiming that the nation of Qatar “has historically been a funder of terrorism at a very high level”. This came about while Saudi Arabia and its Gulf allies initiated a joint campaign to isolate Qatar, which eventually proved completely ineffective. Not even six months later, Qatari Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al Thani was once again sitting next to the US President, who labelled him a “friend of his” and a helpful force in fighting terrorism. In a densely interwoven development of events, Qatar did in fact manage to find an elegant way out of a situation which once seemed insolvable.

Now fast-forward into present-day America, which abounds in Qatari investment in oil and gas projects – some of them are already known, some will emerge with time. First the Qatari Sheikh promises investments into US oil and gas, both conventional and unconventional, then the contours of Qatar operating an LNG terminal in Texas emerges and Doha pledging to invest to the order of $20 billion in US energy. The drift towards the United States serves a double purpose – it changes attitudes towards Qatar, easing the international pressure on the Middle Eastern nation (just as Rex Tillerson would have urged), whilst also diversifying Qatar away from Europe and the Middle East and making sure the impending US LNG wave will happen to the financial benefit of Doha.

Qatar Petroleum, the national oil company and absolute backbone of the economy, is no stranger to American companies. ExxonMobil is already involved in a plethora of LNG trains on the North Dome supergiant gas field, has set up a joint venture called Ocean Marketing to trade in non-Qatari LNG volumes, sold stakes in two Vaca Muerta blocks in Argentina and filed joint bids with Qatar Petroleum during licensing rounds in Brazil and Cyprus. ExxonMobil will also be teaming up for the 10 billion Golden Pass LNG project in Sabine Pass, Texas, which is expected to produce 16mtpa of LNG per year from 2024 (Qatar Petroleum owns 70 percent of the project, with ExxonMobil taking the rest).

Just on a sidenote, one has to underscore that the Qatar-ExxonMobil link is definitely in the interest of the U.S. oil and gas major. Qatar, having lifted the moratorium in 2017 on new development projecs in the North Field, the world’s largest gas field containing an estimated 900Tcf of natural gas shared with Iran (which uses the South Pars denomination), now intends to build four trains with a production capacity of 7.8mtpa each and ExxonMobil, already the leading international major involved in Qatari operations, seems a very probable candidate for this.

Qatar’s good relations with the United States provide another reasons for its decision to quit OPEC, despite being in the ranks of the oil cartel since 1961. First and foremost, quitting OPEC staves off the risk of any NOPEC-related fallout completely. Secondly, Saudi Arabia has been working very hard to stop gas flaring altogether and kick-start its domestic gas production with an eye on establishing its own LNG portfolio. Doha would break under the strain of popular anger if Qatar were to endure year-long Saudi sanctions only to see it build up its LNG sector. Thirdly, it eliminates the prospects of Qatar having to live under imposed production cut levels at a time when its 600kbpd oil sector faces newly created market opportunities

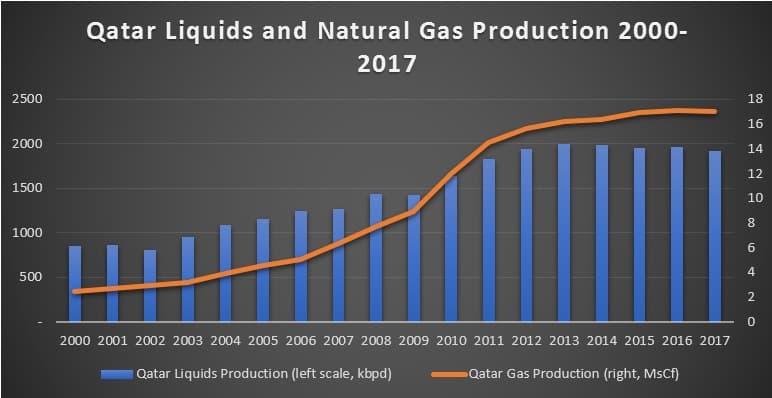

(Click to enlarge)

Source: BP Statistical Survey 2018.

The United States’ foreign policy (read: sanctioning frenzy) will also boost Qatar’s standing, both vis-a-vis Washington and East Asian nations. The thing is Iran was a major condensate supplier to refiners in South Korea and Japan whose splitters preferred South Pars condensate due to its low acidic, mercury and metals content and relatively low logistics costs. However, with the (first round) of US waivers running out on May 05, 2019, both Asian countries will turn towards Qatari condensate as early as mid-March (it takes roughly 30 days for a South Pars Condensate-laden vessel to reach South Korea or Japan) as it is both the most plentiful and the most accessible variant.

Having said this, we would urge against looking at Qatari condensate prices a credible forecasting instrument. The Qatari Deodorized Field Condensate (DFC) hit 6-year lows last week, dropping to a whopping -2.5 USD per barrel discount against the Platts front-month Dubai. Yet behind it lies a subtle acknowledgement of an impending Qatari rebound as South Korean and Japanese firms, not having bought any Iranian condensate (or any other crude oil for that matter) from the onset of sanctions until mid-January have gone a buying spree in February to render their supplies sanctions-compliant from April onwards.

If you think Qatar, by means of skillful maneuvering, intense political lobbying and flooding relevant entities with cash, has done a pretty good job overall, be aware that it gets even better. As it ramps up its North Dome production 77mtpa LNG per year to 110mtpa LNG per year, QP’s subsidiary Qatargas intends to double its commercial fleet by a further 60 vessels. Most of the vessels are going to get produced at South Korea’s shipyards – during the last 2010 tender it was Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering, Samsung Heavy Industries and Hyundai Heavy Industries, a potentially massive market outlet for Qatari condensate. Moreover, the 60-vessel order will comprise tankers that will operate on the Golden Pass LNG project so even here Qatar managed to score a point, albeit a relatively minor one.

Qatar will also bolster its non-energy involvement in the U.S. economy, making good on its erstwhile promise of investing $45 billion in the US, primarily real estate, IT and other technologies and exchanges. Oil and gas, however, are still far from clear as Sheikh al Thani promised 20 billion in U.S. investment, yet so far only half of it materialized – the most reasonable path forward would be to invest in U.S. upstream projects so as to fully back up Golden Pass LNG. Golden Pass is supposed to be bidirectional, i.e. if conditions allow Qatar would most likely bring in its own LNG to American markets. But apparently Qatar also takes great interest in exporting US gas volumes, more than 2 BCfd according to initial plans, which means that either it relies on ExxonMobil providing the goods or takes a much more substantial position on the U.S. gas production market. And by all appearances, the preference is for the latter.