Italy in June is a tremendous place to be. The exquisite beaches of the Amalfi Coast, the green hills of Tuscany, the eternal hustle and bustle of Rome, what more can one ask for. Interestingly, however, Italy became the venue of a quite peculiar case revolving around the presence of an oil-laden tanker outside of Milazzo, one of the biggest Italian ports. By examining the specific example of MT White Moon, one can see a general scheme of things in how Iran copes with quasi unilateral US sanctions and what prospects does it face in doing so. The picture is rather bleak for Iran as buyers, even those with a high appetite for risk, seem to be aware of the risks inherent in dealing with Iranian crude.

When Italian media started reporting last week on a stranded tanker near Milazzo, the energy world barely took notice – it focused on the US-China trade wars and devoured news about the upcoming OPEC/OPEC+ summit. The cargo, according to official documentation some 600 000 barrels of Iraqi crude, was carried aboard the Suezmax vessel White Moon and was expected to be discharged in Milazzo, home to the 235kbpd Milazzo Refinery which is co-owned by the Italian oil major ENI and the Kuwaiti national oil company KPC. The discharge, however, never happened. According to ENI’s official press release, the crude aboard White Moon was “not compliant with the chemical and physical specifications required (by ENI)”.

This seemingly inconspicuous release harbors a set of questionable…

Italy in June is a tremendous place to be. The exquisite beaches of the Amalfi Coast, the green hills of Tuscany, the eternal hustle and bustle of Rome, what more can one ask for. Interestingly, however, Italy became the venue of a quite peculiar case revolving around the presence of an oil-laden tanker outside of Milazzo, one of the biggest Italian ports. By examining the specific example of MT White Moon, one can see a general scheme of things in how Iran copes with quasi unilateral US sanctions and what prospects does it face in doing so. The picture is rather bleak for Iran as buyers, even those with a high appetite for risk, seem to be aware of the risks inherent in dealing with Iranian crude.

When Italian media started reporting last week on a stranded tanker near Milazzo, the energy world barely took notice – it focused on the US-China trade wars and devoured news about the upcoming OPEC/OPEC+ summit. The cargo, according to official documentation some 600 000 barrels of Iraqi crude, was carried aboard the Suezmax vessel White Moon and was expected to be discharged in Milazzo, home to the 235kbpd Milazzo Refinery which is co-owned by the Italian oil major ENI and the Kuwaiti national oil company KPC. The discharge, however, never happened. According to ENI’s official press release, the crude aboard White Moon was “not compliant with the chemical and physical specifications required (by ENI)”.

This seemingly inconspicuous release harbors a set of questionable issues. First, if ENI genuinely believed to be buying Basrah Light, it must have been ready for substantial quality volatility as the Iraqi crude hovers anywhere between 28 and 31 degrees API depending on the single-point mooring point at the ABOT Terminal. Second, the quality of loading port documentation from Basrah pales in comparison to established trading hubs yet, even so, ENI had its ways of telling whether the cargo had been acceptable or not. Thirdly, nowadays it is very rare to come across a spot cargo of Basrah Light (fascinatingly, this cargo was bought from a barely known Nigerian firm Oando) against the background of SOMO cracking down on all market fissures and trying to exercise maximum control over where its cargoes go.

In the end, MT White Moon spent three weeks next to Milazzo only to sail away towards the Suez Canal. The vessel currently states its destination as Fujairah, UAE. With the departure of the oil tanker, Iraqi state oil marketer SOMO chipped in with its bit, claiming that MT White Moon did not load at the port of Basrah, hence can only carry crude which was transferred to it via an STS (ship-to-ship transfer). It is neither SOMO’s own crude nor some oil major’s, e.g.: China’s Unipec, equity crude. According to some reports MT White Moon did, in fact, conduct an STS, some miles off the port of Basrah from the VLCC New Prosperity, which most probably contained Iranian crude. This gives you an explanation of why ENI eventually declined the vessel.

The case of White Moon is not a singular one, Reuters has already reported on a similar story with regard to Iranian fuel oil exports, disguised as Iraqi produce with forged SOMO documentation to prove it. The same has existed in the 2012-2015 sanctions period, with mixes of Iranian Light and Iranian Heavy comingled together so that the mix resembles Basrah Light or the Omani Blend. The peculiarities of such deals have barely changed – there generally is a long supply chain, coupled with several STSs along the way so as to obfuscate matters even more, so that it is basically impossible to trace the offered crude back to its origins. In a sense, this is completely to be expected as Iran has been seeing its crude exports plunge to 0.4-0.5mbpd in May-June 2019.

Iran’s maneuvering possibilities are somewhat weakened by the fact that it is predominantly dubious traders, many those from nations that do not necessarily invite confidence, that are willing to put Iranian volumes on the market. These traders routinely offer Basrah Light with discounts that are completely at odds with current market trends, automatically evoking suspicion in the eyes of the responsible buyer. At the same time, it must be said that not all Iranian cargoes which are sailing the seas are smuggled or counterfeited. Despite the onset of the total Iran export oil embargo by the Trump Administration, starting May 05, there have been deliveries to Asian countries that went under the radar, given their one-off character.

The VLCC oil tanker Horse loaded on June 02, 2019 at Kharg Island and for a long period of time it remained difficult to foretell where it would eventually move as the ship’s destination point bluntly stated “Asia”. However now it seems the vessel, laden with roughly 2 MMbbls of Iranian crude is destined to arrive to Dalian, China in a couple of days. MT Stark I, owned and managed by Iran’s national shipping company NITC, loaded June 08, 2019 and is bound to arrive in the upcoming 2-3 days in Turkey with some 1 MMbbls of Iranian crude on board. Another NITC-run vessel, the Silvia I Suezmax, loaded a couple of days after Stark I and is roaming around the UAE port of Fujairah, making it a potential candidate for an upcoming ship-to-ship transfer.

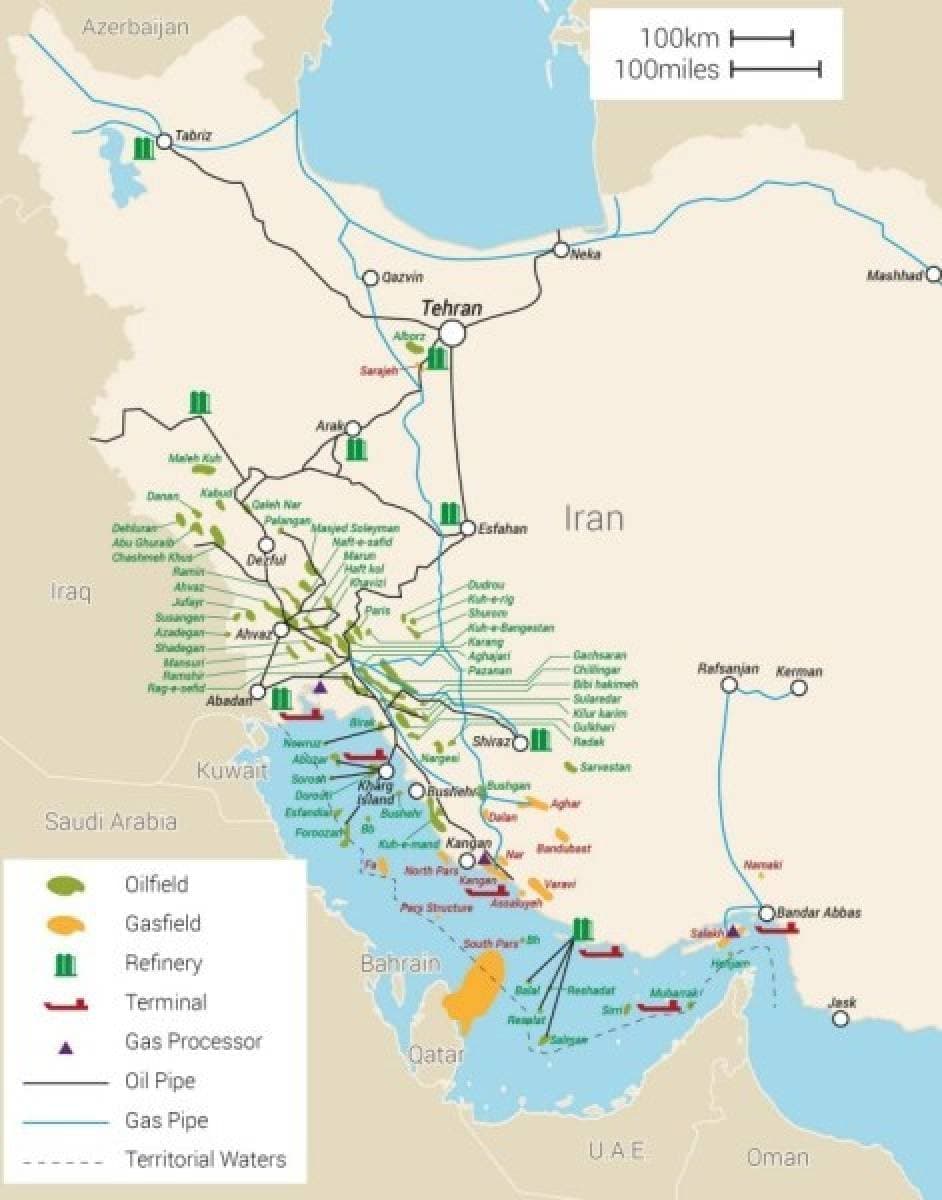

As one might have gathered from the information above, NITC vessels that are located in the Persian Gulf with their automatic identification system (AIS) switched off are very difficult to locate. Checking vessel tracking software lately has become a highly entertaining pastime – of the more than 70 vessels NITC has been operating, not all can be pinpointed on a map. Whichever vessel tracking software one uses, they will find a handful of vessels, usually 5 or 6, around the main crude logistics hubs of Iran – Kharg Island, Assaluyeh and Bandar Abbas. In most cases, these are the ones used as floating storage, similar to the practice we have seen during the 2012-2015 sanctions campaign when the first round of Iranian crude to arrive in Europe and Western countries was actually from VLCC tankers around Kharg Island.

Moreover, as any attentive reader of Oil & Gas Insider would attest, Iran has been working for quite some time on “domesticating” its oil – freeing up (still unsanctioned) gas for exports, whilst using oil and condensate as the primary energy feedstock of the nation. Having reached a national aggregate refining capacity of 2.15mbpd, Iran has ceased gasoline imports altogether and has made great headway in bringing its 400kbpd condensate splitter Persian Gulf Star close to its nominal capacity. Hence, Iran’s main challenge from now on would not be saturating the domestic product market (which is by all accounts well supplied) but the procurement of foreign currency with some 75 percent of its exports now sanctioned. Russia has promised to participate in a 100kbpd “crude-for-services” deal which would see half of the crude’s worth paid back in cash, yet that is small solace for Tehran.