In the fourth (and last) episode of our overview of the US crude export boom, we will now look at the United States’ waning energy relationship with the Middle East. The US shale boom is at the core of US refiners relinquishing Middle Eastern crudes, despite the latter being generally heavier and sourer – the distance renders purchases of Saudi or Iraqi crudes economically questionable, hence the bulk of heavy barrels American refiners need come from Canada and Mexico, forcing traditional supply partners to seek their luck elsewhere. Middle Eastern producers might not be worse off from this – following President Trump’s sanction crusade against Iran, regional peers have hurried to fill in the gaps in Chinese and Indian supply needs.

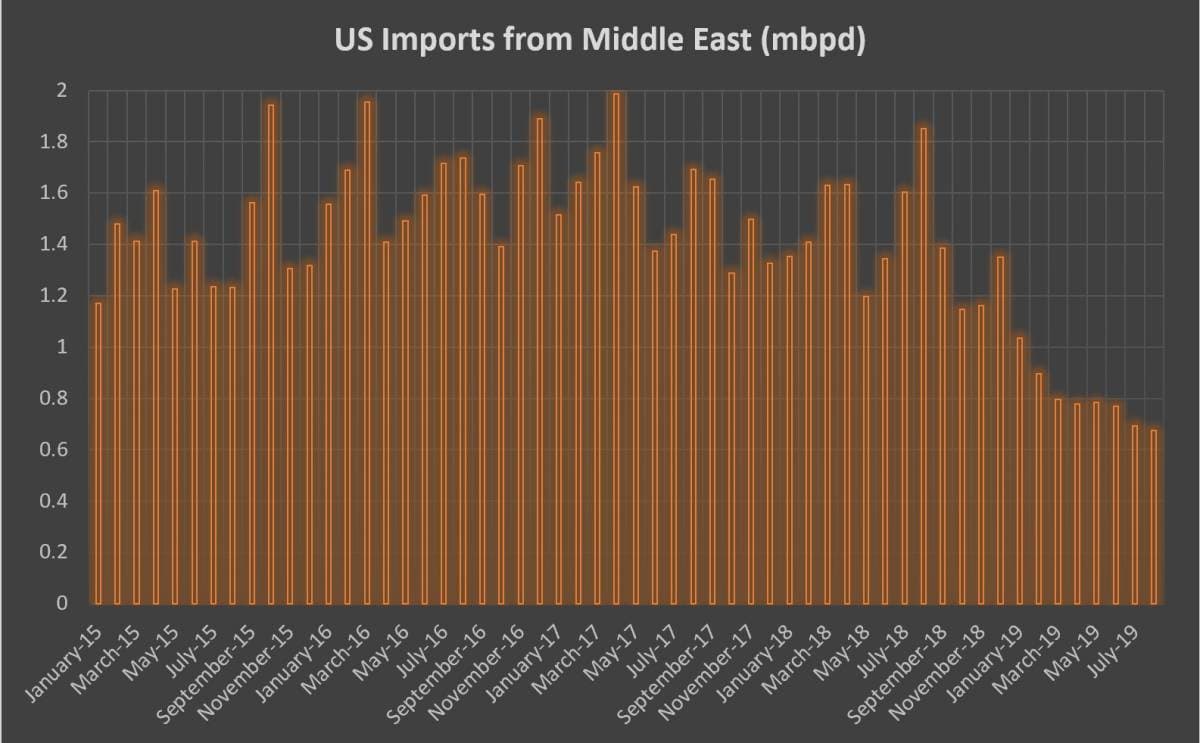

Let’s look at the statistics first. For most of the 2010s, the United States imported some 1.4-1.6mbpd of Middle Eastern crudes – primarily from Saudi Arabia but also from Iraq and Kuwait. Despite the President Obama-era rapprochement between the US and Iran, US refiners did not buy a single cargo of Iranian crude – in fact, the last year when Iranian volumes reached the United States was 1992 (before the Islamic revolution Iranian exports to the USGC were substantial, averaging 380kbpd throughout the 1970s). In less than 3 years, Middle Eastern exports to the United States halved, averaging 0.8mbpd so far this year and sliding further down every consecutive month of 2019.

The most sizable drop in absolute export volumes…

In the fourth (and last) episode of our overview of the US crude export boom, we will now look at the United States’ waning energy relationship with the Middle East. The US shale boom is at the core of US refiners relinquishing Middle Eastern crudes, despite the latter being generally heavier and sourer – the distance renders purchases of Saudi or Iraqi crudes economically questionable, hence the bulk of heavy barrels American refiners need come from Canada and Mexico, forcing traditional supply partners to seek their luck elsewhere. Middle Eastern producers might not be worse off from this – following President Trump’s sanction crusade against Iran, regional peers have hurried to fill in the gaps in Chinese and Indian supply needs.

Let’s look at the statistics first. For most of the 2010s, the United States imported some 1.4-1.6mbpd of Middle Eastern crudes – primarily from Saudi Arabia but also from Iraq and Kuwait. Despite the President Obama-era rapprochement between the US and Iran, US refiners did not buy a single cargo of Iranian crude – in fact, the last year when Iranian volumes reached the United States was 1992 (before the Islamic revolution Iranian exports to the USGC were substantial, averaging 380kbpd throughout the 1970s). In less than 3 years, Middle Eastern exports to the United States halved, averaging 0.8mbpd so far this year and sliding further down every consecutive month of 2019.

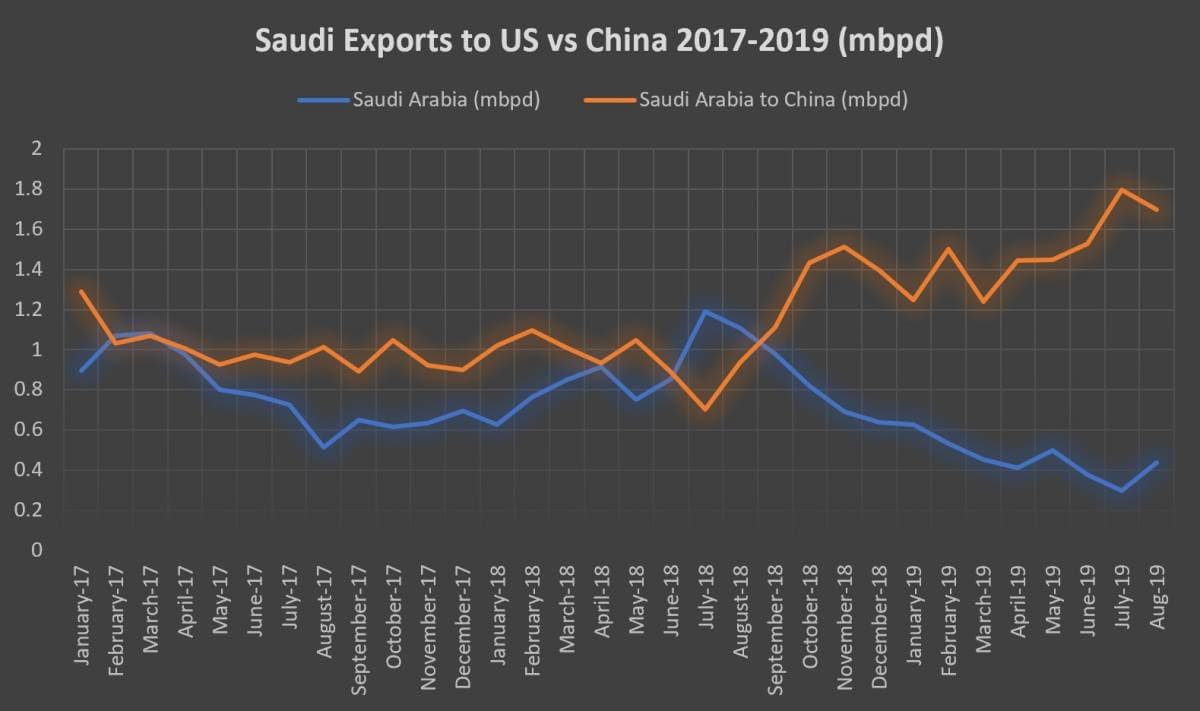

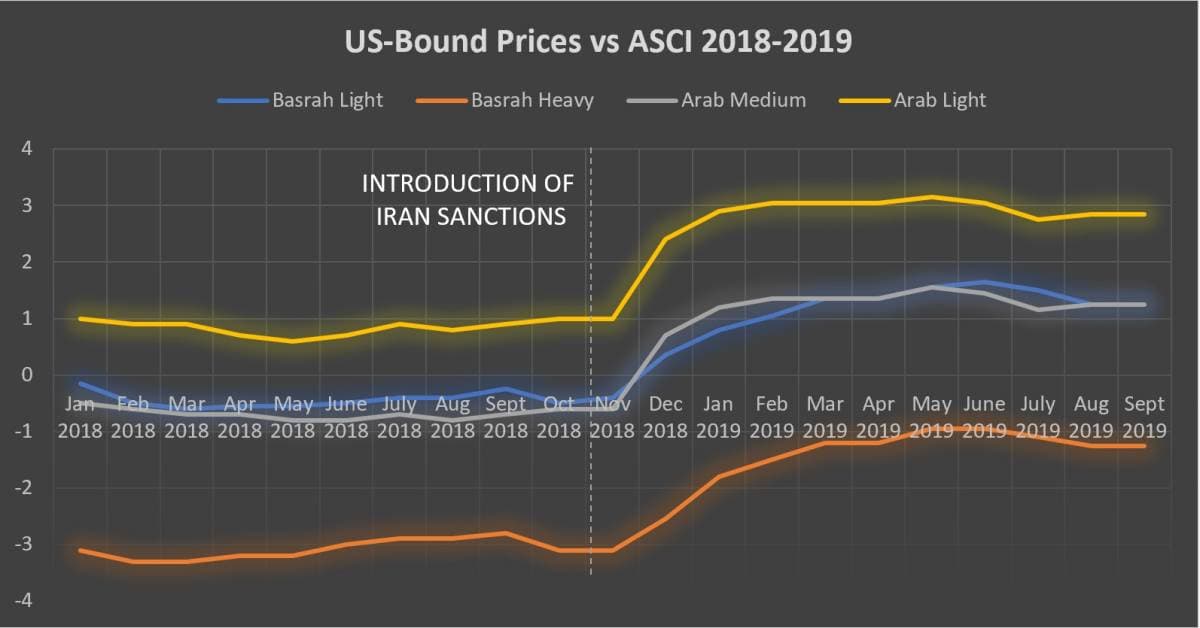

The most sizable drop in absolute export volumes falls to the share of Saudi Arabia – Saudi Aramco routinely delivered more than 1mbpd throughout the previous years, yet this year’s average stands at a meager 0.45mbpd. Yet if one is to look at the graphs above and below, it becomes more than evident that such a drastic shift is primarily due to the levy of Iran sanctions by the Trump Administration. First, the bifurcation in the volumes of Saudi exports to the US and China correspondingly takes place in September-October 2018, i.e. just a couple of weeks before the introduction of the first round of sanctions vis-à-vis Teheran. Second, pricing developments of leading Middle Eastern streams corroborate this suggestion – in November 2018, all medium sour crudes jumped some $2 per barrel month-on-month as Iranian availability was depressed.

It has to be pointed out that the loss of Middle Eastern crude imports is not a negative development for the United States – US refiners can source crude from their own upstream production, creating a win-win situation. The only adverse consequence lies in Middle Eastern national oil companies’ diverting their attention from the United States in terms of investment – despite Saudi Aramco spending heavily on the Chinese, Indian or South Korean downstream segment (providing beneficial long-term supply conditions in return). Thus, the flow of Middle Eastern money into the US is most likely going to be limited with LNG – both Saudi Arabia and Qatar have been confirmed/rumored to buy stakes in Gulf Coast-based LNG projects.

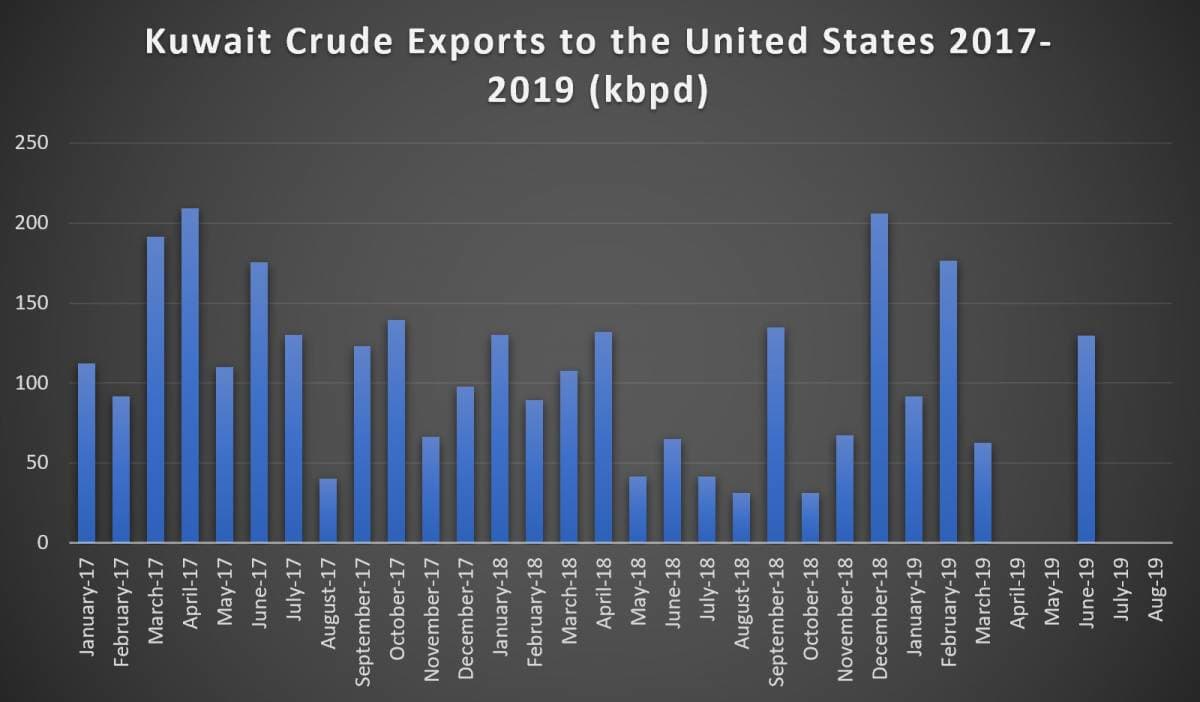

The story of Kuwaiti exports to the United States is one of a seemingly terminal decline. This is all the more noteworthy as, ever since the 1990-1991 Gulf War, Kuwait was exporting crude to American customers every single month for 26 consecutive years. Again, this does not mean that Kuwait’s NOC, KPC, is any worse off from such an outcome – exports to Far East Asia generally garner $1 per barrel more than USGC does this year. Omani supplies to the US have dried up by the end of 2017 and have not picked up since – even before the onset of the sanctioning frenzy China intercepted exports from Oman and has been occasionally using them to finetune the Oman/Dubai prices it wants to see.

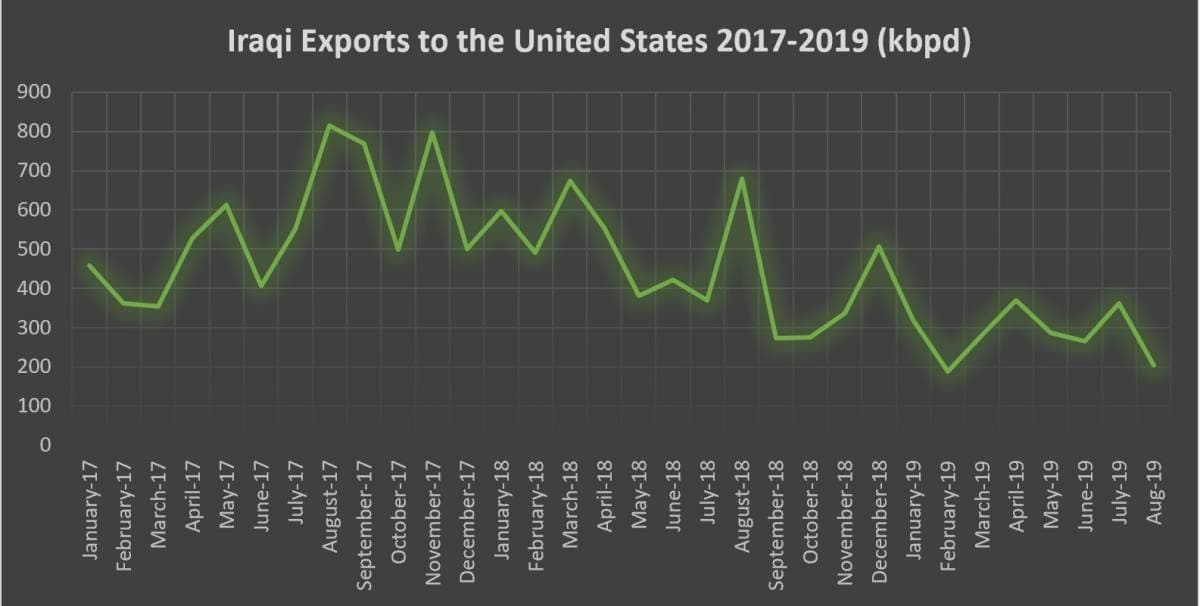

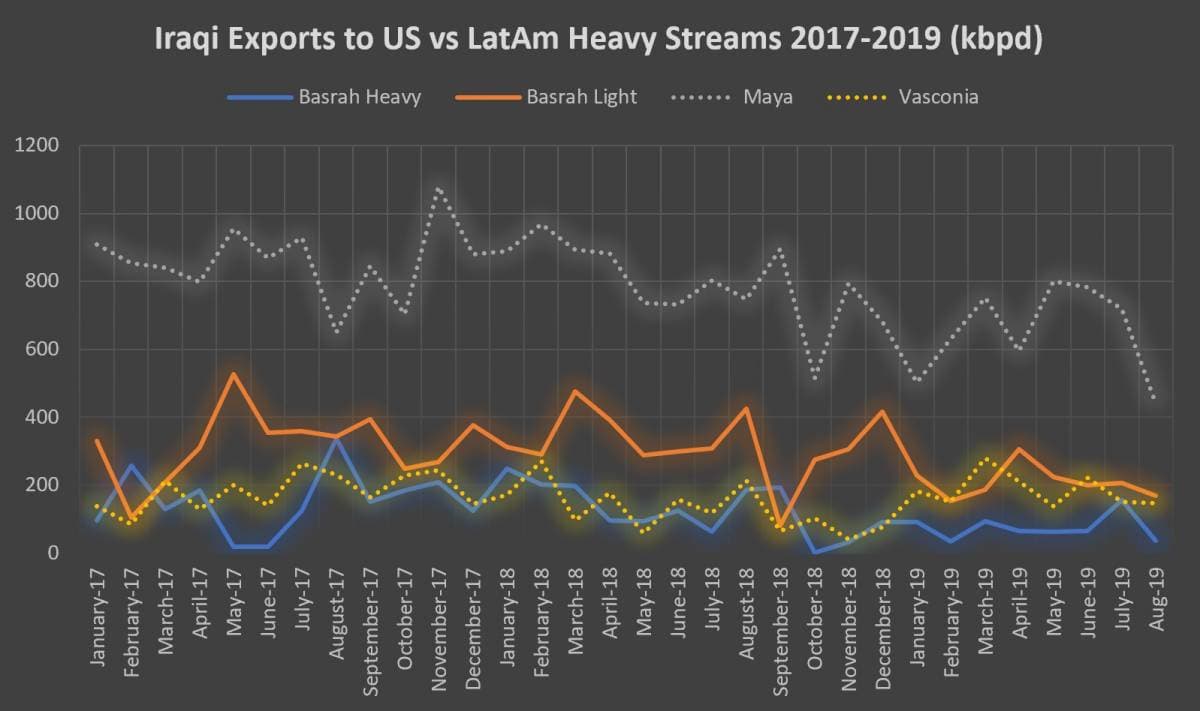

Alright, in the ebb and flow of global crude trading routes there is nothing surprising in the Middle East turning away from US markets, yet one would think Iraq to be a different case. After all, ExxonMobil’s $50 billion West Qurna-1 contract, Chevron’s Sarta and Qara Dagh blocks in Iraqi Kurdistan stand in stark contrast with Saudi Arabia or Kuwait where the totality of upstream operations is in the hands of the domestic NOC. Nevertheless, Iraqi crude exports to the United States have dropped from the 2017 annual average of 554kbpd to the 284kbpd registered this year so far. Cognizant of the fact that US imports of lighter Mexican streams have all but dried up, one might expect that the heavier part of Iraqi exports – Basrah Heavy – would at least decrease at a slower rate than the lighter Basrah Light.

However, quite the opposite is true. When compared to 2017 numbers, Basrah Light has dropped 35 percent in 2019 YTD to 209kbpd, whilst Basrah Heavy has effectively halved to 75kbpd. For the sake of comparison, one should note that the Mexican Maya has dropped 24 percent in the 2017-2019 period whilst the Colombian Vasconia has, in fact, increase 2 percent to 185kbpd. Now, one might speculate that if Middle Eastern exports to the United States are decreasing amid OPEC/OPEC+ production caps, US exports to the Middle East might increase instead. Yet this year saw only 2 US-origin cargoes being delivered to the United Arab Emirates, both of them carrying Eagle Ford condensate from Corpus Christi, Texas. Given that in 2018 there were 15 such cargoes, hardly a positive development.

All in all, the resume of the Middle East-US crude link sounds rather dreary. Excepting the war-heavy year of 2015 when Iraq’s war against ISIS raged on, this year will mark the lowest level of Iraqi crude exports to the US since 1998. For Saudi Arabia, the statistics are of even higher– if the trend set in January-August 2019 continues, Saudi Aramco will have the lowest level of exports to the US since 1986. Interestingly, the decline in bilateral energy ties does not seem to sadden anyone – US refiners can source their crudes from domestic fields and lighten their refinery slates, Middle Eastern producers can reorient their exports towards the Asian Far East and new emerging demand hubs. Thus, the gist of the cooperation will now tilt towards LNG.