The last two weeks have seen quite a flurry of news about Russia taking its Arctic projects to the next level, tapping into the “colossal” reserves of this still somewhat underdeveloped production region. In order to grasp the complexity of the task Russia faces with all its indisputably bountiful Arctic zone, one has to analyze bit by bit the paradoxes and undercurrents of its oil production in general – then you might understand how Gazprom Neft can claim at the same time that it “can do anything in the Arctic” yet is actively looking for partners to reduce production costs. The renewed interest in the Arctic is in large part a by-product of the oil price rise, so if Dated Brent drops below $60 per barrel, plans could be shelved once again.

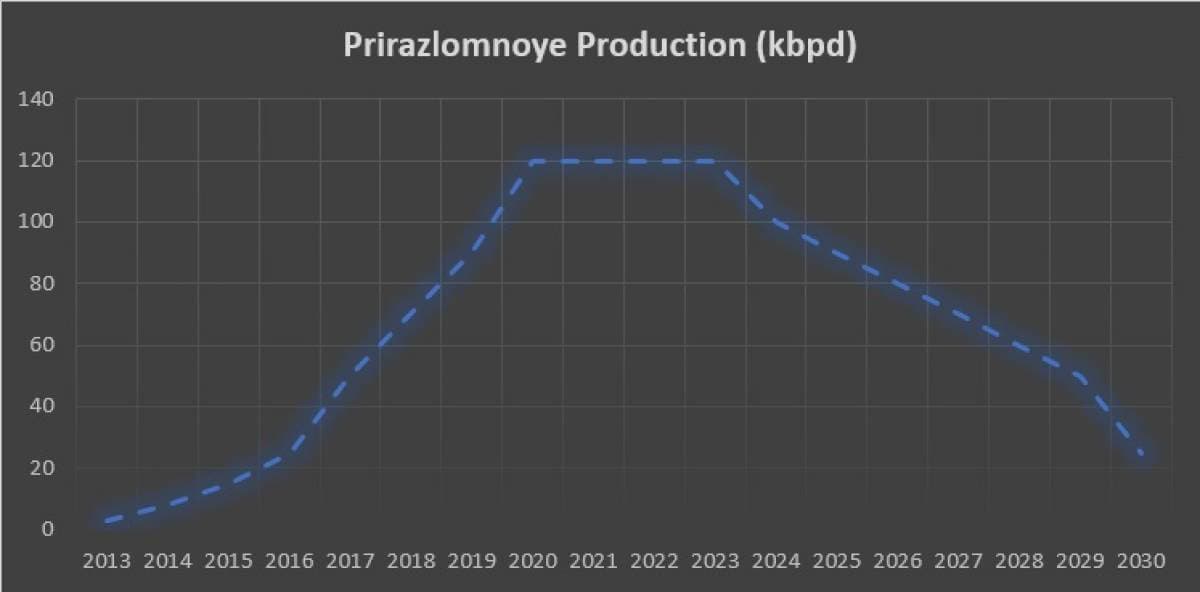

Despite substantial Western hype about Russia pumping as much Arctic crude as it can, on the surface of it, Moscow’s success list is bleak with no evident promise of changes to come. After the Russian government modified the Subsoil Law in 2009, allowing only Rosneft and Gazprom Neft to operate Arctic and continental shelf projects, there is only one company – Gazprom Neft at its Prirazlomnoye field – producing Arctic oil. Gazprom Neft also claims that its Messoyakhinskoye and Novoportovskoye fields belong tot he Arctic category, yet both are technically onshore (for that matter, the mother company Gazprom does not call its Yamal gas fields, like Bovanenkovo, Arctic). Ever since the US sanctions on Russia, Russia’s leading major…

The last two weeks have seen quite a flurry of news about Russia taking its Arctic projects to the next level, tapping into the “colossal” reserves of this still somewhat underdeveloped production region. In order to grasp the complexity of the task Russia faces with all its indisputably bountiful Arctic zone, one has to analyze bit by bit the paradoxes and undercurrents of its oil production in general – then you might understand how Gazprom Neft can claim at the same time that it “can do anything in the Arctic” yet is actively looking for partners to reduce production costs. The renewed interest in the Arctic is in large part a by-product of the oil price rise, so if Dated Brent drops below $60 per barrel, plans could be shelved once again.

Despite substantial Western hype about Russia pumping as much Arctic crude as it can, on the surface of it, Moscow’s success list is bleak with no evident promise of changes to come. After the Russian government modified the Subsoil Law in 2009, allowing only Rosneft and Gazprom Neft to operate Arctic and continental shelf projects, there is only one company – Gazprom Neft at its Prirazlomnoye field – producing Arctic oil. Gazprom Neft also claims that its Messoyakhinskoye and Novoportovskoye fields belong tot he Arctic category, yet both are technically onshore (for that matter, the mother company Gazprom does not call its Yamal gas fields, like Bovanenkovo, Arctic). Ever since the US sanctions on Russia, Russia’s leading major Rosneft did not spud a single wildcat in the Arctic.

Source: OilPrice data.

Even if it wanted to (it does not as it is busy seeking preferential fiscal treatment at onshore sites), Russia in total has only two drilling rigs that are applicable in Arctic conditions. Of course, one would not hear it on the news – the externalized image is that of Rosneft CEO Igor Sechin meeting with President Vladimir Putin, vowing to create an Arctic production hub that would facilitate Putin’s plan of increasing Northern Sea Route shipments fourfold by the end of his mandate in 2024. The devil is in the details here – Rosneft claims that oil from its Vankor hub fields, like Tagulskoye or Suzunskoye, could be rerouted towards the north, technically making them “Arctic” crude even though they are very well within the borders of continental Siberia. Yet this would mean diverting them away from their current outlet conduit – the Vankor-Purpe pipeline and ESPO which currently carries this crude into China.

Rosneft has all but monopolized crude exports towards China – 90 percent of all Russian exports towards its eastern neighbor are Rosneft volumes – so basically creating an Arctic hub would mean foregoing lucrative ESPO exports. Moreover, the Vankor-Purpe pipeline was not built by the Russian pipeline transportation monopoly Transneft, but Rosneft itself – giving up on a $1.5 billion investment that is operational only since 2009 would be a tough call, even for a company as profligate as Rosneft is. Hence, all the recent Arctic talk is nothing but throwing dust in the eyes of the largely unsuspecting populace. Most likely it’s just doublespeak for further exclusive preferential Rosneft tax cuts or getting the Zapadno-Irkinsky block without appropriate licensing rounds held.

Ironically, roughly around the same time that the Rosneft CEO was boasting about his company’s Arctic potential, the head of the Russian subsoil agency Rosnedra Evgeniy Kiselev had a rare moment of complete honesty, stating that “both Rosneft and Gazprom Neft are blocked at Arctic deepwater projects” and that Russia’s progress in this aspect was severely constrained by a lack of relevant technical competence. The crux of the matter that US sanctions against Russia’s oil and gas sector – banning any sort of cooperation in shale, deepwater and Arctic - have not bitten that much into Russia’s shale potential (there LUKOIL and Gazprom Neft still vie to develop an extraction technology suitable for the country’s cold climate and capable of reducing high production costs), but instead have blocked everything related to the Arctic.

Yet if there was a moment in the past 5 years when investments into Russia’s Arctic area would be finally appropriate, it is now. The authorities feel it and are trying to nudge the two state-owned companies to act. According to most Russian analysts, the breakeven point for commercially viable Arctic fields hovers somewhere between 65 and 80 USD per barrel – note the weird phrasings of high-ranking managers saying that the production cost is less than 10 USD per barrel after the company has completed investment. This, under current circumstances, is a workable that might excite potential investors. Two years ago, when Gazprom Neft lured ONGC and CNPC to join the Dolginskoye project (3P oil reserves of 1.5Bbbl) crude prices were around $50-52 per barrel – today a potential investment seems much more likely.

Yet fear still fetters Western and Chinese majors – since 2014, Russia has seen a total of 31 shelf development plans abandoned or delayed. Even though the Russian deputy prime minister Yuri Trutnev raised the idea of clearing all administrative obstacles in front of foreign firms to develop fields located on Russia’s continental shelf, including Arctic ones, it is not the Russian state hindering their involvement in the first place, rather punitive measures that the Trump Administration might take against anyone who might have the nerve to invest in Russia’s Arctic (and deepwater generally). With such a constellation of stars, companies like Gazprom Neft, might be much better off focusing on Russia’s shale (Bazhenov Suite and the likes) where the distinction between “shale” and “tight” oil is very vague – thus, a strong legal case might be made that one is developed (the allowed) tight, not the banned shale oil .

If one is to take the utterances of the Natural Resources Ministry in earnest, one must also notice the frequent usage of the peak crude demand phenomenon. There has already been a lot of speculation around this in the past decades, however the current consensus of sorts (top-tier tradinghouses’ estimates) boils down to crude demand growing until the 2030s, wherefrom terminal decline starts. Russian authorities also expect peak demand in the 2030s and are worried that unless they ramp up the appraisal of the Arctic now, they might be simply too late to the party. Yet at least they would make it to the party at some time – Russia’s only proper Arctic contender, Norway, is thinking about giving up on new prospects altogether.

Last week the Norwegian Labour Party, Norway’s largest in the parliament, has backtracked on its promise to support exploration drilling around the Lofoten archipelago, estimated to contain up to 3.4-3.5 billion barrels of oil equivalent. As the Norwegian continental shelf grows increasingly mature and depleted, Equinor and all the other companies producing in Norway are asking the government to open up the far north for exploration – if it worked for Johan Sverdrup, the North Sea’s largest project in the 21st century, it might work for other projects too. This takes place against the backdrop of the Norwegian sovereign investment fund vowing to progressively quit oil and gas assets, worth some $8 billion.