As any attentive reader of our Oil & Gas Insider feature would attest, the oil market is in constant flux and one nation’s fate might drastically swing from that of a net oil importer to that of a rising export star. The story of the United States’ “shale gale” represents the apogee of just how quickly things can change in the world of energy – merely a couple of years ago the US was the world’s largest oil importer and had its crude exports banned by law, now it is the world’s most formidable producer with ever-increasing export volumes. We think the time has come to take stock of the recent developments in US exports and imports and take a thorough look at the 4 major trends that have shaped it – the plunge of Middle Eastern crude exports to the US, the US’ complex relationship with Latin America and the new horizons opening up in Asia and Europe.

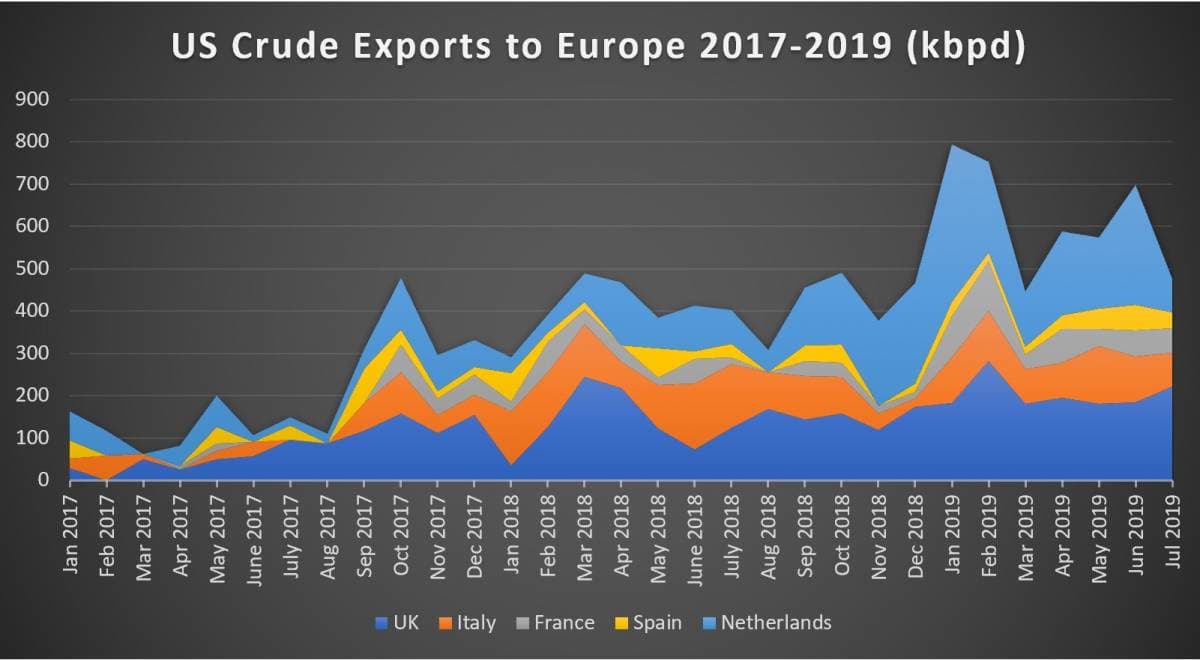

In the next 4 issues of Oil Insider we will take a look at each one of those, but for now, let’s start with Europe. Despite Asia maintaining its position as the leading market outlet for US crude, Europe saw the biggest upward movement percentage-wise in the timeframe between January 2017 and August 2019. American exports to European customers effectively tripled in the past 3 years, moving up from an average of 207kbpd in 2017 to 635kbpd in YTD 2019. One might say that US foreign policy greatly contributed to this achievement, by banning all Iranian and Venezuelan exports from the European market, yet the reality is…

As any attentive reader of our Oil & Gas Insider feature would attest, the oil market is in constant flux and one nation’s fate might drastically swing from that of a net oil importer to that of a rising export star. The story of the United States’ “shale gale” represents the apogee of just how quickly things can change in the world of energy – merely a couple of years ago the US was the world’s largest oil importer and had its crude exports banned by law, now it is the world’s most formidable producer with ever-increasing export volumes. We think the time has come to take stock of the recent developments in US exports and imports and take a thorough look at the 4 major trends that have shaped it – the plunge of Middle Eastern crude exports to the US, the US’ complex relationship with Latin America and the new horizons opening up in Asia and Europe.

In the next 4 issues of Oil Insider we will take a look at each one of those, but for now, let’s start with Europe. Despite Asia maintaining its position as the leading market outlet for US crude, Europe saw the biggest upward movement percentage-wise in the timeframe between January 2017 and August 2019. American exports to European customers effectively tripled in the past 3 years, moving up from an average of 207kbpd in 2017 to 635kbpd in YTD 2019. One might say that US foreign policy greatly contributed to this achievement, by banning all Iranian and Venezuelan exports from the European market, yet the reality is a bit more nuanced. The main grades to be exported into Europe are WTI and Bakken, significantly lighter and sweeter than anything Iran or Venezuela can offer.

Despite US crudes reaching a plethora of new markets (including occasional rarities like the one delivery to Belgium, two deliveries to Lithuania and Turkey since 2017) in the recent past, the main thrust of the US crude expansion into Europe passes through the United Kingdom. Roughly a third of all Europe-bound US deliveries end up in the United Kingdom, averaging 203kbpd so far this year. The arrival of US crudes has in upended the previous modus operandi in the North Sea, compelling local producers to move their crudes outside of the Old Continent. Hence, Forties now almost completely goes to China even though just a couple of years ago it was predominantly refined in Europe. Add to this the narrowing of the Brent-WTI spread and voilà, Norwegian crudes such as Ekofisk are now moving in the other direction to US refiners in increasing numbers.

The United Kingdom was also the first European country to witness the emergence of a first-ever term contract late July as Essar Oil UK, the subsidiary of the Indian Nayara Energy consortium operating the 296kbpd Stanlow Refinery in Cheshire, sought six cargoes (one every month) between October 2019 and March 2020. Despite no official confirmation, it was rumored that Vitol has won the tender and will now ensure the Stanlow Refinery’s US incoming stream. Obviously, the crude slate tilts towards the lighter side – the conditions of the tender stipulated that the supplied crude should be WTI, WTL, Eagle Ford or Bakken. Medium sour grade Mars has so far struggled to gain a trans-Atlantic foothold. Essar previously issued tenders, oftentimes cross-month ones, to supply its system yet in a somewhat rare ambitious move committed to a longer-term.

Here one must observe that surges in demand for US crudes is still somewhat seasonal – for instance, after remarkably robust demand in January-February 2019 came a trough in March-April, only to repeat the same thing again with June-July and August-September (at least as far as we can judge by how things stand today). Also, amidst all the bombastic muscle-flexing that surrounds the Iranian and Venezuelan sanctions, it is quite easy to forget that US crudes actually did not and will not displace either of them. The Trump Administration banished them, yes, however, US grades now compete with the Caspian flagship crude CPC, Algeria’s Saharan Blend and Libya’s light sweet grades, as well as almost all of West African production, not medium sour or heavy barrels.

Take, by way of example, the Mediterranean, one of Iran’s most sorely missed market outlets. For the medium sour barrels, i.e. equivalent of anything Iran can offer, Mediterranean refiners chose to supplant Iranian Light with Urals, hence the all-time high premium on the Russian crude. Saudi Arabia was never really interested in the Med, whilst Iraq could have reacted, however, was also swayed by the lure of Southeast Asian markets, higher premiums and less speculation (the Mediterranean was one of the epicenters of Basrah Light re-trading, a practice SOMO wants all but eliminated. One of the biggest losers of the US crude onslaught to Europe is Nigeria, seeing its exports to the United States zeroing out for the first time this decade in July 2019.

Nigerian producers have found some solace in China, whose demand for low-sulfur crudes seems insatiable as the country readies itself for IMO 2020 compliance, yet there are some structural signs that Nigeria might be in for more trouble than it currently does. August and September loadings in Nigeria this year witnessed a rare occurrence as dozens of front-month cargoes were still available at a time when the next-month loading schedule was published – i.e. as much as 40 cargoes were still available in mid-July when the September schedule came out. Refiners also noticed the Nigerian oversupply tensions in Europe, receiving more and more offers from sellers on distressed Bonny Light cargoes.

The second-biggest importer of US crudes in Europe, is an illustrative case of how having a global network that includes both upstream and downstream segments can help in paving the way for new trends. Take ExxonMobil and BP, both of which have refineries in Rotterdam and both of which have significant assets in US’ upstream sector and readily bring crude produced in the US to their European downstream assets. France’s leading buyer of US crudes is the ExxonMobil-owned Fos Refinery (in fact only two deliveries were not to Fos but to Lavera), attesting once again to the idea that output equity holders in America have the least seasonal exposure of all. Italy’s prime delivery point is Trieste, the starting point of the TAL pipeline, with Vitol, Mercuria and Trafigura vying for the top trading supplier spot.

Some countries perceived the onset of US crude imports into Europe as a means of political rapprochement with the Trump Administration. Lithuania bought two cargoes in 2017 yet has given up on American crude afterward. Poland promised early this year that it will ramp up US imports as it seeks to minimize its dependence on Russian Urals supplies, however, has failed to buy any up to now. Ukraine, freshly after the presidential elections, bought a Bakken cargo in June 2019 and vowed to continue doing so ever after, reverted back to its traditional staple diet of Azeri Light after that. Occurrences such as the above are far from being the last on the list, yet they rather prove to be distractions from important trends that have a long-lasting effect on Europe’s crude market.

Most notable among them is the lightening of Europe’s refinery crude slate as a result of US crudes arriving in greater numbers. Betting on the long-term presence of US crudes in Europe and availing themselves of the different grades that US producers offer, some refiners have used US grades to create a new refinery configuration. Hellenic Petroleum’s Aspropyrgos Refinery, which previously ran on heavier crudes like Basrah Light or Kirkuk, has tested several US crudes to create a new lighter slate of palatable grades. Similar developments took place in the Spanish refineries of Bilbao and Tarragona, with possibly some other countries joining the club very shortly.