For much of the 2010s, Rosneft was the leading force on the Russian domestic crude market. It is one thing to produce 42-43 percent of Russia’s crude production, indubitably noteworthy in and of itself, yet Rosneft also wielded significant political power, being able to proactively shape the country’s energy policy (whilst other majors were mostly in a spectator’s position). Recent moves might indicate that Rosneft’s power might be curbed politically as government officials tire of its one-off tax exemptions and constant haggling overproduction terms, apparently so much that President Putin needs to get involved.

Rosneft’s firm political backing allowed the company to get away with several fiascos – just recall the 2016 “privatization” of Bashneft (in the end the tender did not take place and the government simply passed the majority stake in Bashneft onto Rosneft) or the subsequent auctioning of a 19.5 percent stake in Rosneft itself which saw the Chinese CEFC, holding 14.2 percent of Rosneft in 2017 go bankrupt and transfer its stake to the Qatari investment fund QIA under remarkably murky circumstances. These brought about no repercussions, although Rosneft was manifestly more cautious in 2018-2019, with the CEO Igor Sechin repeatedly claiming that from now on the company would focus on “organic growth”, i.e. no more hostile takeovers.

With the repartition of the Russian oil market no longer an issue (one might have heard a sigh of relief in regionally…

For much of the 2010s, Rosneft was the leading force on the Russian domestic crude market. It is one thing to produce 42-43 percent of Russia’s crude production, indubitably noteworthy in and of itself, yet Rosneft also wielded significant political power, being able to proactively shape the country’s energy policy (whilst other majors were mostly in a spectator’s position). Recent moves might indicate that Rosneft’s power might be curbed politically as government officials tire of its one-off tax exemptions and constant haggling overproduction terms, apparently so much that President Putin needs to get involved.

Rosneft’s firm political backing allowed the company to get away with several fiascos – just recall the 2016 “privatization” of Bashneft (in the end the tender did not take place and the government simply passed the majority stake in Bashneft onto Rosneft) or the subsequent auctioning of a 19.5 percent stake in Rosneft itself which saw the Chinese CEFC, holding 14.2 percent of Rosneft in 2017 go bankrupt and transfer its stake to the Qatari investment fund QIA under remarkably murky circumstances. These brought about no repercussions, although Rosneft was manifestly more cautious in 2018-2019, with the CEO Igor Sechin repeatedly claiming that from now on the company would focus on “organic growth”, i.e. no more hostile takeovers.

With the repartition of the Russian oil market no longer an issue (one might have heard a sigh of relief in regionally owned Tatneft and private Lukoil which were rumored to be “interesting” for Rosneft), the Russian national oil company set its sights on tax breaks. This has put Rosneft on a collision course with Russia’s Finance Ministry and other relevant institutions that have claimed that it would be unwise to prioritize oil companies’ interests over those of the country’s citizens. For quite some time, however, it seemed that Rosneft would simply overpower the Finance Ministry and keep on clinching tax exemptions, cognizant of its heavy debt load and committed to pay it out as soon as possible.

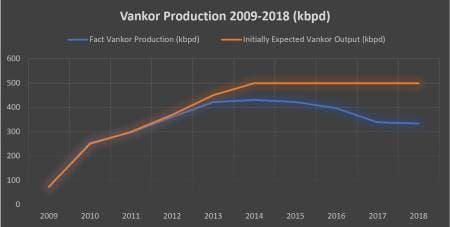

Vankor was the harbinger of things to come – Rosneft has secured in 2017 a then-unprecedented 10-year tax break on the giant field, production at which started plummeting unexpectedly after a mere 6 years of development. Then came the idea on multiplying drilling costs by a factor of 2.5 in tax declarations so as to boost exploration drilling (Rosneft claimed this measure would have led to 5000 additional wells spudded in 2019-2024) – the idea was nipped in the bud – and further attempts to gain tax exemptions for oil fields that just seemed to difficult to handle. The timing was key in Rosneft’s quest – Russia’s main production region, West Siberia, has moved into (a seemingly) terminal decline in 2008 and the need for activity-stimulating measures was evident.

In general, most of the tax concessions in Russia are allocated to fields above the 80 percent depletion rate, with a high water cut or with hard-to-recover, high-viscosity reserves. In most cases, the concessions take the form of mineral extraction tax (MET) breaks, only a little more than a dozen projects availed themselves of having a lower export duty. This makes sense as all Russian producers pay the MET, yet only the exporters deal with the export duty – smaller firms generally sell their volumes to traders or state-owned mediums-size companies like Zarubezhneft because it is quite difficult for them to secure a place in Russia’s trunk pipeline system that generally delivers the crude from upstream spots in Siberia to European or Asian ports.

In a way, Rosneft sees its tax exemptions as a sort of payback for it bearing the brunt of OPEC/OPEC+ production cuts, yet it seeks to achieve much more than that. For an illustrative case look no further than CEO Igor Sechin’s push for a mind-boggling tax exemption package for Arctic fields. First, the Arctic for some odd reason includes also Vankor, Suzun and Tagul (which were previously classified as West-Siberian fields). Second, the sheer magnitude of tax breaks surpasses all conceivable records – Rosneft claimed that if it is exempted from some $41 billion of taxes, it would invest in Arctic development almost $120 billion over the upcoming decades. Almost needless to say, Russia already discounts Arctic fields with a discounted mineral extraction tax rate, so these breaks would be a one-off for Rosneft.

It is against this background that President Putin has first asked the government to justify giving new tax breaks to Rosneft and introduced a moratorium on all new state support solicitations until December 31, 2019 (by which an internal audit has to be done so as to assess the efficiency of the previously provided tax breaks). At some point, a political decision will cut the Gordian knot – considering Russia’s future production is going to be from harder-to-recover reserves and coming from less prolific / more mature oil fields, the Russian subsoil agency’s finding that under current oil prices and taxation regime two-thirds of its 12 Bbbls future (not present) reserves are commercially feasible casts a long shadow on the oil companies’ narrative.

Currently, a little bit more than 52 percent of oil fields are in one way or another using tax breaks. The Finance Ministry has been reiterating its claims that if current norms are upheld in the future, too, by 2035 up to 90 percent of Russian crude production would be basically state-subsidized, without necessarily entailing a substantial output increase (if any). That Russian oil production is to drop is by no means a novelty, media speculation about the impending start of decline being just around the corner has been an organic part of the oil industry since the early 2000s. Yet with no more major (i.e. proven reserves more than 100 million tons) oilfields held by the Russian subsoil agency – the last was the Erginskoye field, no surprise, won by Rosneft in 2017 - future greenfield development will be inevitably linked to smaller fields.

Adding to the domino effect, the Russian Energy Ministry presented late September its new initiative – setting the mineral extraction tax rate at 30 percent of the standard rate for oil rim projects (i.e. fields where oil is extracted from the rims of gas fields), implying a successful lobbying drive by Gazprom. It is Gazpromneft that develops most of currently active oil rim projects, either on a risk-service agreement from the gas-focused parent company Gazprom or by itself with international partners like Royal Dutch Shell, be it the Yamal-Nenets Pestsovoye, Yen-Yakhinskoye or Tarkosalinskoye fields or the Far Eastern Chayandinskoye field. Gazpromneft estimates its current oil rim reserve potential might allow it to produce 280-300kbpd of crude at peak levels.

Scaling back tax concessions would be increasingly difficult with time as Russia gradually taps into its hard-to-recover potential and starts producing shale oil from the Bazhenov, Domanik and other formations. Under the current legislation, Russian shale oil producers would pay no mineral extraction tax whatsoever and only a fraction of the export duty. We have already covered the Russian Finance Ministry’s somewhat awkward quest to switch oil sector taxation towards a profit-based one (instead of the current across-the-board MET + export duty), yet companies which are already MET-exempted simply do not want this switch, claiming that the existing tax breaks are “more efficient” (in the words of Tatneft).

As of today, the high-viscosity fields of LUKOIL and Tatneft in Western Siberia are subject a $2 per barrel tax rate, whilst conventional Western Siberian output is taxed at $28-29 per barrel. For Russia as a whole, it would be politic to call a final moratorium on one-off concessions and tie every single exception to strictly technical parameters. When state-owned companies lobby the state for arbitrary concessions, clearly something has gone awry. Yet for that to happen (and for the Finance Ministry’s rather pragmatic guidelines to take place) the whole setup of contemporary Russian politics ought to be altered, US/EU sanctions would have to be cleared and private enterprise would have to be encouraged on a grand scale. Judging from today’s standpoint, that's highly unlikely to happen anytime soon.