Media reports have been awash with speculation this week, some pointing to the inevitability of a production cut extension, some highlighting the growing tensions in the Russia-Saudi Arabia-Iran triangle and some advocating a gradual return towards a free-for-all competition against the background of Iran and Venezuela sanctions. If one is to analyze the current economic state of leading oil producers, then everything is indicative of an OPEC+ extension – Russia, Saudi Arabia, Iraq and others are afraid of oil prices tanking, all the more so after the developments of the last couple of weeks. But let’s look at them one by one, so that you see it for yourself.

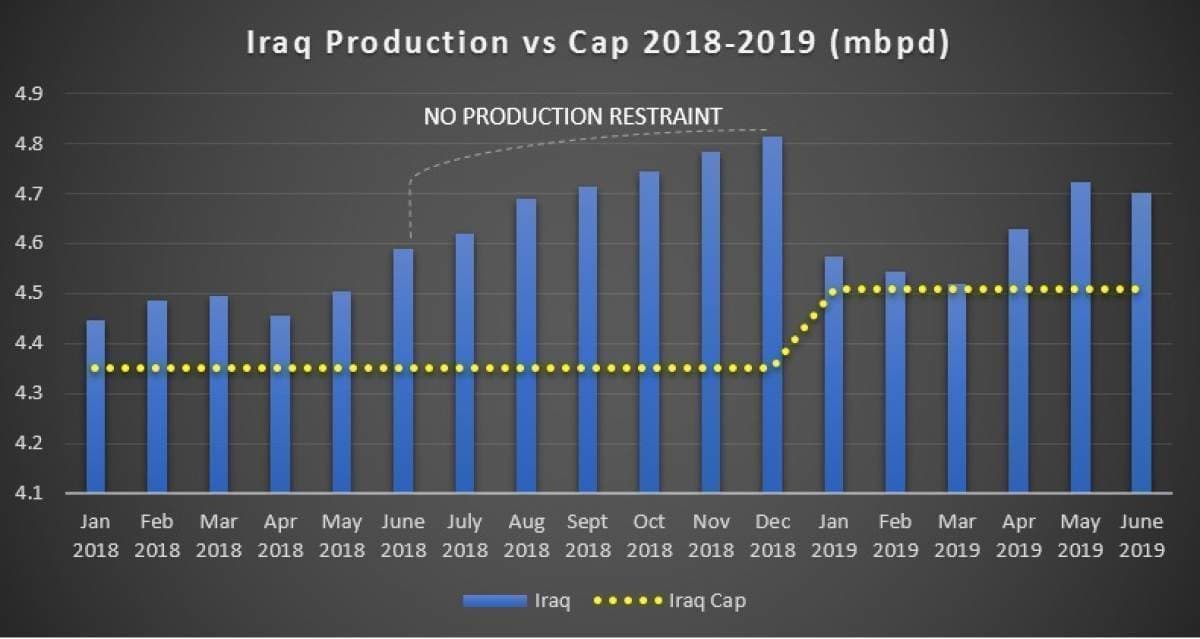

First, one has to highlight how effectively did OPEC+ manage to adhere to the set production caps. Whenever output discipline was needed, all major producers complied with the Vienna Agreements; whenever the oil market allowed for a production ramp-up, Saudi Arabia, Russia and the UAE did so, only to scale it back under the 2019 production ceiling (it took Russia 3 more months than others, yet this came as no surprise as Moscow generally shrinks from cutting rates in the winter). The exception only proves the rule - Iraq has been something of an enfant terrible of OPEC but encountered little public scorn due to its post-Islamic State conditions and strategic position vis-à-vis the Iran “problem”.

The root cause for this author’s optimism with regard to a new OPEC/OPEC+ deal lies in the producing nations’…

Media reports have been awash with speculation this week, some pointing to the inevitability of a production cut extension, some highlighting the growing tensions in the Russia-Saudi Arabia-Iran triangle and some advocating a gradual return towards a free-for-all competition against the background of Iran and Venezuela sanctions. If one is to analyze the current economic state of leading oil producers, then everything is indicative of an OPEC+ extension – Russia, Saudi Arabia, Iraq and others are afraid of oil prices tanking, all the more so after the developments of the last couple of weeks. But let’s look at them one by one, so that you see it for yourself.

First, one has to highlight how effectively did OPEC+ manage to adhere to the set production caps. Whenever output discipline was needed, all major producers complied with the Vienna Agreements; whenever the oil market allowed for a production ramp-up, Saudi Arabia, Russia and the UAE did so, only to scale it back under the 2019 production ceiling (it took Russia 3 more months than others, yet this came as no surprise as Moscow generally shrinks from cutting rates in the winter). The exception only proves the rule - Iraq has been something of an enfant terrible of OPEC but encountered little public scorn due to its post-Islamic State conditions and strategic position vis-à-vis the Iran “problem”.

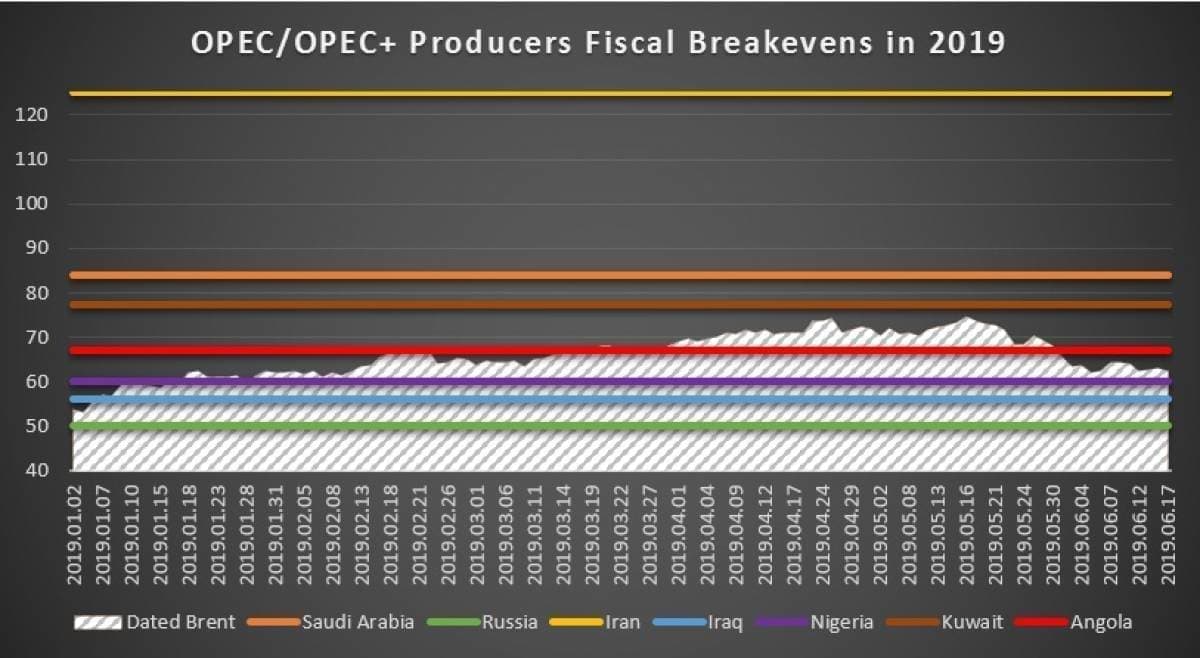

The root cause for this author’s optimism with regard to a new OPEC/OPEC+ deal lies in the producing nations’ fiscal breakeven levels. If one is to consider the graph below, one finds that only one major producer – Russia – was in a comfortable zone throughout 2019 to date. No country comes even close to Russia as countries roughly in the same category, like Iraq or Nigeria, are obfuscating several important facts. For instance, Iraq routinely states its fiscal breakeven at $56 per barrel, however, its 2019 budget is already planned with a $23 billion gap, hence its genuine breakeven is significantly closer to $70 per barrel.

Even if we acknowledge the imprecision implied, Russia, Iraq, Nigeria and to a certain degree Angola would be content to see crude prices where they are currently, in the $60-70 per barrel interval. Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Iran, however, have not had a single day this year when the daily price of Brent (for the sake of the thought experiment, let’s just assume they all trade on par with Brent even though in real life the overwhelming majority of their grades are traded at discounts to it) traded above their fiscal breakeven levels. Venezuela did not even fit into the above graph as it would need Brent prices above $200 per barrel to balance its budget, an unwitnessed feat in the history of energy markets.

Russia

Russia’s time-delaying tactics with regard to setting the exact date of the OPEC/OPEC+ meeting should not mislead anyone – Moscow is highly interested in seeing the production curtailments extended further into the year and possibly even 2020. This is primarily due to the impossibility of foretelling where prices would move were the Vienna deal not to be extended – for Russia, anything below $50 per barrel is sub-optimal as it would trigger the risk of running a budget deficit, something which the Kremlin wants to achieve after 12 unavailing years. Moreover, with Urals differentials nosediving recently and the (heretofore) unpredictable character of IMO 2020 regulations impact, Russia would not act against its natural interests. The only thing which it might pull off is to delay the start date of the new production cut agreement so as to max out the summer oil-pumping season.

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia has been the most driven participant of the OPEC/OPEC+ deal, adhering to its production quota when needed, then swiftly ramping up production when conditions dictated so, only to lead the way again with output cuts deep enough (more than 0.5mbpd q-o-q in Q1 2019) to impress the crude trading community. Every economic indicator attests to the fact that Riyadh needs the quota extension – the $84 per barrel fiscal breakeven level (that some analysts already tentatively put at $95 per barrel due to the lingering war in Yemen), the repercussions of the regional rivalry with Iran, perhaps even Mohammad bin Salman’s personal desire to prove that this time Saudi Arabia means business all contribute to the overall picture.

Iraq

Iraq was the least-compliant participant to the OPEC/OPEC+ output cut agreement in absolute terms (Kazakhstan was trying really hard though to replicate the Iraqi recalcitrance), yet its commitment to the OPEC/OPEC+ production curtailments remains immutable. Without drawing the ire of neighboring Iran, Iraq could fill the gaps that were created as a result of the US sanctioning spree and, just to name one example, managed to ramp up crude exports to India above 1mbpd. For a long time already, Iraq needed a period when it could muster the necessary fiscal muscle and finally invest into its decrepit infrastructure, upgrade its existing refineries and build new ones so that it no longer relies on product imports and has the financial depth to find a fair solution to the Kurdish income redistribution issue. Now that it finally got such a period of “getting off the ground”, it would be inexpedient to release hold.

Iran & Venezuela

The 2018 statistics of OPEC compliance were substantially skewed by Iran and Venezuela, both countries complied against their own will and under pressure of U.S. sanctions. No doubt about it, there is a distinction between the two – Iran’s output started to tank exclusively due to the sanctions, whilst Venezuela’s production levels have been falling ever since President Maduro came to power. Hence, should a political solution regarding the Iran deal come on the table that would also rescind the US oil embargo, the Iranian national oil company NIOC can kick-start production within a matter of months, something that Venezuela can only dream about. All in all, both Teheran and Caracas display great activity with regard to the OPEC/OPEC+ extension even though the chances of either of them being subjected to any production quotas is minimal.

Algeria, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, Mexico, Oman, Sudan and Others…

Virtually every participating country that is not Saudi Arabia, Russia or to a lesser extent the UAE, produces as much as it can and could have not surpassed the output quotas stipulated in the Vienna covenant even if it desperately wanted. This, of course, was taken into consideration when setting the production caps – take Ecuador whose monthly production never left the 0.51-0.53mbpd range since the onset of the voluntary curtailments (against the background of a 0.52mbpd quota). In a similar vein, Mexico, faced with a Gargantuan task of halting 13 years of continuous production declines, would gladly take up any output cap because it knows it would surely live up to it (and witness further production drops).

There seems to be only one “hot” wildcard currently – Libya. Nigeria was also previously considered one, but it did a laudable job in fulfilling its 2019 production quota of 1.69mbpd and given President Buhari’s re-election should be able to continue the streak. Kazakhstan, too, had issues with sticking to the set maneuvering space as it ramped up Kashagan production but should be more amenable to discipline now. Libya, however, is a geopolitical scratch card after Field Marshal Haftar’s raid on Tripoli – depending on who has the upper hand and where, the North African country’s crude production might be anywhere between 0 and 1.3mbpd, therefore it is very likely that once again Libya will be exempted from the production cap system.