Seven years after South Sudan became independent, leaving behind a sanguinary civil war, it finally reached the point where it places its bets on development and not on incessant internal conflict. The basis for this is this August’s Khartoum agreement between President Salva Kiir and a former vice president-turned-rebel leader Riek Machar, putting in place a total ceasefire and opening up the way for economic development for the war-torn country. Ironically, the country from which South Sudan wanted to break away, Sudan, is now a crucial partner in rebuilding the world’s youngest nation’s shattered infrastructure and shut-in production wells. What does it mean for the international oil community, though?

The united Sudan was a relative newcomer to the oil sector, having started oil production in 1999. This, however, did not interfere in oil output increasing significantly in the first years of the 21st century, with production peaking at 520 kbpd in 2007. Of course, Sudan’s skyrocketing oil numbers were marred by a genocidal campaign in Darfur that left approximately 300 000 dead and millions displaced. Consequently, Western majors, adhering to their governments sanctioning Omar Bashir’s government, were out of question when it came to invest in Sudan’s oil fields – China (CNPC), Malaysia (Petronas) and India (ONGC) stepped in to fill the void and thoroughly enjoyed the full tax exemption of the oil industry. The commitment of Asian majors is often unjustly understated – for them at the time, Sudan was the largest foreign producing asset and a highly profitable one at that.

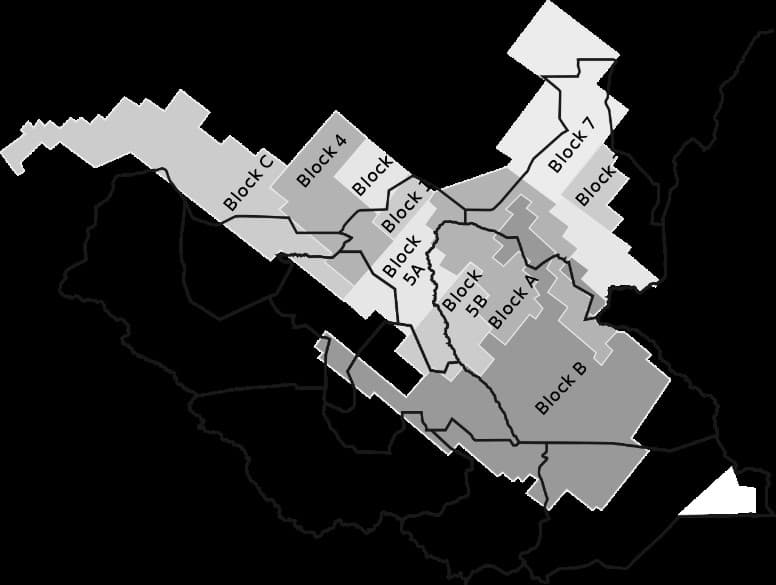

(Click to enlarge)

The inclusion of Asian state-owned enterprises made life certainly easier for Sudan itself – with no shareholders’ opinion to take into account apart from the respective state, the government could wage war or suppress dissent with no repercussion whatsoever to its oil production. The most prolific oil fields of the once-united nation are located across territorial boundaries, further complicating issues of ownership, yet even this could be overcome with slight legal maneuvering. The civil war, however, could not be circumvented. As a result, most of South Sudan before this August was temporarily shut-in. Related: Saudi Oil Income Could Reach $161B This Year

Oil production continued only in the Upper Nile states – what was before 2015 a singular state are now three separate (Central, Northern and Western Upper Nile). Output in the central part, incorporating the Liech states, Ruweng and Tonj has been close to naught due to constant skirmishes. For it is there that the trans-Sudanese oil pipeline starts, at the Unity oil field next to the city of Bentiu and it is there where most of the Muglad rift basin’s reserves lie. Even from the point of view of trade economics, South Sudan ought to concentrate heavily on the safety and integrity of the Muglad Basin – the quality of oil produced there significantly surpasses that of the Upper Nile provinces.

Sudan and South Sudan share the same crude blends – Upper Nile states yield the Dar blend (26° API, 0.12% Sulphur), whilst the central part of the country is rich in a blend called Nile (32-33° API, 0.05% Sulphur). Both blends are notoriously problematic when it comes to their paraffinic and acidity content, especially so the Dar blend which also contains high levels of arsenium, making it very difficult to transport and refine. Thus, South Sudan needs not only its current output of Dar – approximately 130 000 bpd – but also its Nile volumes, superior in both reserves capacity and quality. For this, it has pinpointed a target to increase oil output by 80 000 bpd by the end of the year thanks to the unclamping of several Nile-producing assets. Lacking in both expertise and material possibilities, the South Sudanese have turned to the primordial foe, Khartoum, for help and in this lies the biggest weakness of the current political setup.

South Sudan has no refineries (as opposed to Sudan, which has one Chinese-operated 100 000 bpd refinery in Khartoum) and no export outlets other than the South Sudan-Sudan oil pipeline leading to Port Sudan on the Red Sea. Khartoum is interested in South Sudan pumping out as much as possible, largely because the pipeline transportation fee of $25 per barrel (an internationally mediated sum, out of it $16 were designed to compensate for the loss of South Sudan). Now, Khartoum has several more reasons to kick-start South Sudanese production, as the rehabilitation of shattered oil infrastructure, as well as guaranteeing the physical security of workers at South Sudanese production sites will from now on be under (North) Sudan’s control.

The intensification of Sudanese involvement within the upstream segment is in some ways logical, too – the 2011 secession happened a relatively short time ago, so the thorough knowledge of the fields and their geology was one of Khartoum’s widely known secrets. Chinese, Malaysian and Indian investors will also return in force, seeking to remedy their nine-digit losses. Bringing back more than 200 000 bpd worth of production lost since 2011 would be tantamount to a heroic feat, however, its likelihood is quite small. Khartoum has been allegedly helping Riek Machar, the Nuer rebel leader, which in a country as susceptible to rumours as South Sudan might already be considered a fatal blow to national unity. All the more so now, when the Khartoum Accords have created a legal justification for the presence of the Sudanese military on the territory of South Sudan, much to the chagrin of the South Sudanese populace.

Previous ceasefires and seemingly viable reconciliation have failed in South Sudan – an accord similar to the current one was signed on August 2015 and failed spectacularly (with Riek Machar fleeing to DR Congo). Fraught with an infinitude of internal conflicts, it will not be long until either the government of South Sudan or the rebel groups renege on their commitments. That is not to say the government will not try to lure foreign investment into the country – the nation badly needs a refinery not to rely on foreign (read: Sudanese) assistance, moreover, it might seem fit to reach to Western majors with the necessary know-how of treating waxy and acidic crudes.

Related: Can We Expect An Oil Price Spike In November?

Moreover, the south of the country is largely unclaimed and, if the South Sudanese government fulfills its erstwhile promises, it will offer 12 exploration blocks for licensing with Western majors in view. Most notably, Blocks B1 and B2 will be up for offer – by far the largest of the dozen with 44 000 and 48 000 km2, respectively – which attracted the interest of Total and Tullow Oil, however, the discordance between the majors’ expectations and the government’s willingness was too big to bridge. The risks for Western companies are manifold – the travails of Chevron and Shell in Sudan are a conspicuous example of what dangers are there for leading firms.

Shell and Chevron were the first to discover oil in the country under Gaafar Nimeiry’s tenure in the mid 1970s. However, as the President’s doctrinal makeup shifted from socialism to Islamism, precipitating a deadly civil war that was to last more than 21 years, they were all forced to leave (security concerns topped the list, as can be seen from the 1984 assassination of Chevron workers at the Unity field). Despite the conclusion of the Khartoum Accords, South Sudan remains a remarkably polarized society where power sharing arrangements seem to be implemented in an on-and-off mode until one of the sides claims a final victory. For companies keen on extreme risk and no shareholder liabilities, South Sudan might seem a tempting bet, however for the big ones the risks will turn out to be too big not to pay heed to.

By Viktor Katona for Oilprice.com

More Top Reads From Oilprice.com:

- The Biggest Threat To The Oil And Gas Industry

- China Doubled Its Battery Storage Capacity In Just Six Months

- Why Diesel Prices Are Set To Soar