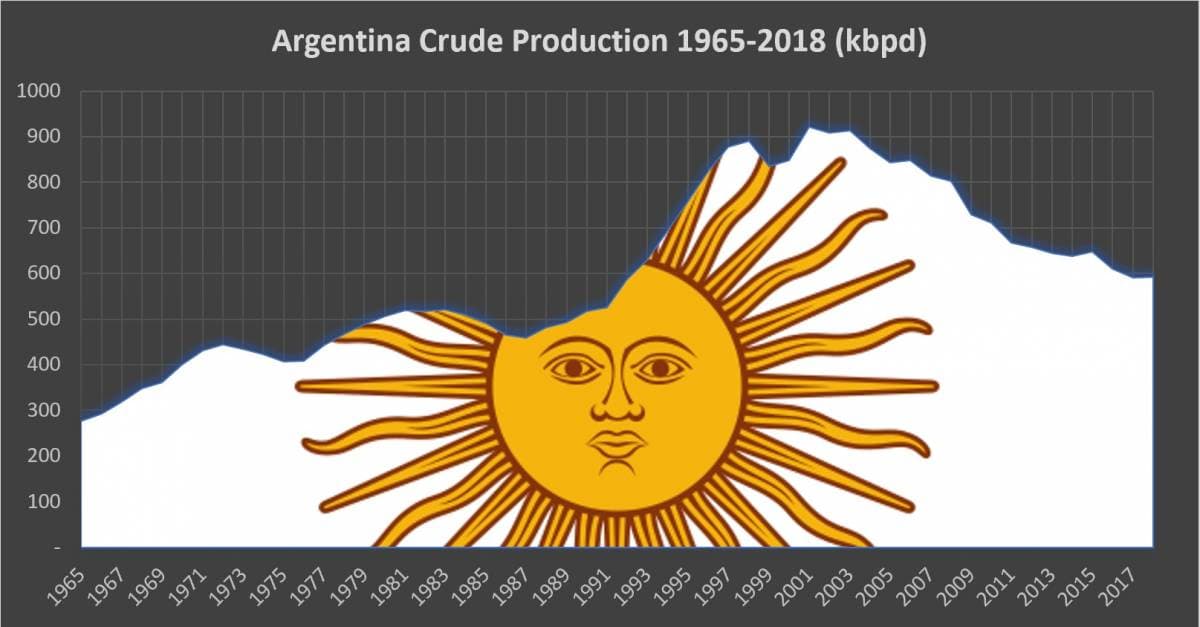

Premature judgments about the fall of Latin America’s left notwithstanding, the pink tide seems to be back in town after Argentina’s national primaries (effectively a nationwide poll ahead of the October elections) saw the opposition candidate, Alberto Fernández, thumping incumbent President Mauricio Macri by a 16-percentage point lead (48 percent to 32 percent). In and of itself a presidential change need not be a problem, were it not for Argentina’s shale production surge that is expected to double the South American nation’s output by 2023 to 1mbpd. The future of Vaca Muerta and Argentina’s shale in general is now frequently put to question, yet are the risks as serious as they are portrayed amidst the market panic?

Let’s start with the facts. The Buenos Aires stock market experienced its second biggest one-day nosedive in history (surpassed only by the 2001 default), with the MERV dropping 48 percent in just one day on August 12. The Argentine peso decreased 15 percent to 52 ARS per dollar. The panic eased on Tuesday, ending the freefall, yet markets remain uncertain where stocks will go next. President Macri did not suffer any official defeat and still harbors ambitions to win, yet his days seem to be counted and the general sentiment has shifted towards a wary contemplation of how populist/interventionist Alberto Fernández will turn out to be.

Despite Macri’s more or less correct portrayal as a pro-market leader, ironically it was the state of the economy…

Premature judgments about the fall of Latin America’s left notwithstanding, the pink tide seems to be back in town after Argentina’s national primaries (effectively a nationwide poll ahead of the October elections) saw the opposition candidate, Alberto Fernández, thumping incumbent President Mauricio Macri by a 16-percentage point lead (48 percent to 32 percent). In and of itself a presidential change need not be a problem, were it not for Argentina’s shale production surge that is expected to double the South American nation’s output by 2023 to 1mbpd. The future of Vaca Muerta and Argentina’s shale in general is now frequently put to question, yet are the risks as serious as they are portrayed amidst the market panic?

Let’s start with the facts. The Buenos Aires stock market experienced its second biggest one-day nosedive in history (surpassed only by the 2001 default), with the MERV dropping 48 percent in just one day on August 12. The Argentine peso decreased 15 percent to 52 ARS per dollar. The panic eased on Tuesday, ending the freefall, yet markets remain uncertain where stocks will go next. President Macri did not suffer any official defeat and still harbors ambitions to win, yet his days seem to be counted and the general sentiment has shifted towards a wary contemplation of how populist/interventionist Alberto Fernández will turn out to be.

Despite Macri’s more or less correct portrayal as a pro-market leader, ironically it was the state of the economy that brought him down. He took over the country at total public debt standing at 48 percent of GDP and will most probably leave it at 83 percent. All the while Macri wholeheartedly promoted the elimination of price controls and unnecessary state involvement, inflation soared to 48 percent last year (with 2019 estimated to be better only marginally, at 41 percent). The USD-ARS exchange rate plummeted from an annual average of 13 ARS per USD in 2015 to 52 ARS per USD right now. Unemployment lingered around 8-9 percent for much of Macri’s tenure, only to surpass the psychological 10-percent threshold this spring. All in all, a perfect storm.

Vaca Muerta output, the world’s second most promising shale boom, was one of the few bright spots of Argentina’s recent performance. Argentina carried out its first-ever LNG export this June, sending 0.0135 mt of liquefied gas from the Bahia Blanca FLNG to Brazil. Against the background of ever-decreasing conventional production, Argentina has hiked its YTD 2019 crude exports to 76kbpd, about three times its 2017 level. The surge in exports (and the forthcoming consolidation of Medanito as Argentina’s flagship export stream) is sure to continue despite costs being generally 20 percent higher than in the US and the 5 percent export tax levied upon the recommendation of the IMF.

Argentina’s downstream segment is largely saturated and unlikely to see substantial growth in the upcoming years – in fact, between 2017 and 2019 both actual refinery runs and capacity utilization rates have dropped across the country. Should the economic malaise persist, this might free up more shale crude than initially thought, further boosting the country’s exports. Similarly to crude, shale gas production from the massive 308 TCf reserves in the Vaca Muerta managed to overturn a seemingly terminal output decline. With only 4 percent of overall Vaca Muerta acreage being in development phase, already 23 percent of Argentina’s gas output is sourced from the shale play. ExxonMobil, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, BP, Shell, Total, Petronas, Wintershall are all simultaneously bringing their projects forward.

Confronted with a lack of information on Alberto Fernández’s oil and gas policy, the trepidation of oil majors that invested billions in Vaca Muerta is understandable. Yet there is some reason to believe that in the eventual case of a Fernandez win, he will refrain from a confrontational course and will primarily seek to placate the markets:

1. He needs to avoid defaulting on Argentina’s debt and would seek the assistance of the IMF (an option which his current running mate Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner discarded in the early 2010s).

2. In contrast to Mexico’s PEMEX which runs the Latin American country’s upstream, YPF is too technologically and financially dependent on Western majors to keep its shale dreams viable.

3. Oil and gas represents the safest lifeline for any Presidential Administration due to agriculture’s volatility, amidst falling financial retail and manufacturing segments (down y-o-y -16, -12 and -6.5 percent.

Although President Macri is right that his 4-year tenure has improved Argentina’s reputation somewhat on the international level – the IMF standby agreement kept the country going despite stagflation, public subsidies were reduced and state pensions cut. Constrained in time and space, Fernández would most probably rectify only those measures adopted by Macri that present clear political advantages (and where the incumbent President has somewhat contradicted his free-market credentials) – lowering interest rates to spur domestic consumption, decoupling electricity prices from peso volatility, eliminating the export tax – whilst keeping the IMF framework intact, despite the occasional rant.

Argentina has many tangible advantages that it could avail itself of. Take agriculture, which propelled the Latin American country in the halcyon days of early 20th century into the realm of Western economies. This year’s agriculture statistics have been remarkably upbeat and buttressed by burgeoning energy exports led to Argentina’s largest trade surplus in the past 7 years (at 4.5 billion for H1 2019). Much of this stems from Argentina shoring up its Asian positions as exports to China and Indonesia spearhead the list of new streams – something which the country will continue with irrespectively of the October election’s winner.

Argentina also stands to benefit greatly from the trade deal between Mercosur and EU that would see the elimination of tariffs on coffee, fruit and juice exports, coupled with an increase in beef, sugar and ethanol quotas. Given the current circumstances, the Mercosur-EU agreement widely favors low-income economies and unless European nations revolt against the pact (French farmers have shown an inclination to do so), Argentina’s exports will be boosted even further. Essentially, if Argentina’s new President manages to control inflation and the depreciation of the Argentine peso, he would be able to augur a new era of across-the-board export growth.

Should Alberto Fernández become President in late October, his policy will be in no small way shaped by his image in the United States. For instance, the fiery Peronist grassroots members might object to the US building a quasi-military base in Neuquén next to Vaca Muerta, yet the new President ought to be careful vis-à-vis American interests as the majority of oil and gas investment comes from US oil majors. Interestingly, this setup was negotiated not in Macri’s time but still under Kirchner (Fernández was briefly her chief of staff until he quit in disagreement over her policies). All US majors entered the Argentine market after the 2012 renationalization of YPF from Repsol, in fact Chevron was one of the first majors to even look at Vaca Muerta at a time of great distrust towards Argentina.

Hence, if the United States does not mind the occasional indignation of the Peronist movement as long as it is used for purposes of domestic policy, US oil and gas majors might greatly benefit from it. Even with a Peronist Fernández as potential president (albeit a moderate one compared to all previous candidates), Argentina needs to be flexible if it wants to cast off the yoke of Latin American nations – stagflation. Even a Peronist Argentina presents little to no foreign policy risk, therefore if the US administrations, present and future, play it right they might find a triple boon in Argentina – plentiful resources, cheap labour and a government loyal to their cause.