October was a truly bloody month for Iraq. Since nationwide protests broke out on October 01 after the ouster of a widely popular counter-terrorism general, more than 260 protesters have been killed and thousands have been injured by security forces in a spate of violence that has engulfed the entire Middle Eastern nation. Last week, more than a million disgruntled Baghdadi citizens occupied the capital city’s Tahrir Square calling for a new round of elections. This is bad news for Iraq in many ways as it paves the way for further political instability, stokes risks of a civil war and brings the Islamic State, thought to be decapitated and shattered, back into the equation.

Let’s look at some of the major consequences of the Iraqi protest wave from an oil and gas investors’ point of view:

1. Iraqi OPEC Non-Compliance is Here to Stay

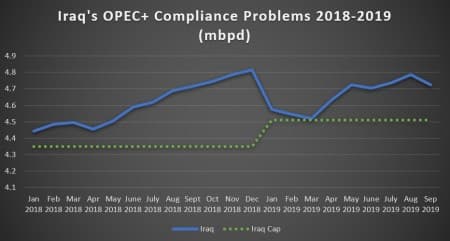

If one is asked to think of a country that failed to comply with its OPEC+ commitments throughout the past two years, the self-evident answer is Iraq (the other rogue element, Nigeria, was exempted from the first phase of OPEC cuts so its history of wrong-doing isn’t as long). Not once in 2018-2019 did Iraq comply with its OPEC+ production quota, generally hovering some 0.2-0.3mbpd above the stipulated norm. With a politically detached caretaker government in charge until the next elections Iraq’s oil companies and SOMO have no incentive whatsoever to deviate from the current line – overproduction brings easy money to Iraq, a…

October was a truly bloody month for Iraq. Since nationwide protests broke out on October 01 after the ouster of a widely popular counter-terrorism general, more than 260 protesters have been killed and thousands have been injured by security forces in a spate of violence that has engulfed the entire Middle Eastern nation. Last week, more than a million disgruntled Baghdadi citizens occupied the capital city’s Tahrir Square calling for a new round of elections. This is bad news for Iraq in many ways as it paves the way for further political instability, stokes risks of a civil war and brings the Islamic State, thought to be decapitated and shattered, back into the equation.

Let’s look at some of the major consequences of the Iraqi protest wave from an oil and gas investors’ point of view:

1. Iraqi OPEC Non-Compliance is Here to Stay

If one is asked to think of a country that failed to comply with its OPEC+ commitments throughout the past two years, the self-evident answer is Iraq (the other rogue element, Nigeria, was exempted from the first phase of OPEC cuts so its history of wrong-doing isn’t as long). Not once in 2018-2019 did Iraq comply with its OPEC+ production quota, generally hovering some 0.2-0.3mbpd above the stipulated norm. With a politically detached caretaker government in charge until the next elections Iraq’s oil companies and SOMO have no incentive whatsoever to deviate from the current line – overproduction brings easy money to Iraq, a much-needed feat in times when the ascension of Sadrists is a real possibility.

The supposedly outgoing prime minister Adel Abdul Mahdi was the closest Iraq could garner in terms of a compromise candidate, at the same time depriving him of genuine political clout as the overwhelming majority of his reforms did nothing but to expand the already bloated public sector. Abdul Mahdi might be the only top-ranking official to leave, i.e. current oil minister Thamer Ghadban has been affiliated with the Sadrist Sairoon movement, hence there remains a possibility that he will stay at the helm of the ministry. This might be helpful in insulating the oil sector from countrywide riots – the evidence so far seems to prove the above point. Employees at the largest state-owned oil subsidiary Basrah Oil actively participated in the riots without threatening (to date) to expand the domain of their struggle to the oil fields.

2. Iraq Will Most Likely Get Another Iran Waiver

In the southern regions of Iraq, the second wave of protests has taken on a markedly anti-Iranian turn, with people torching the offices of political organizations linked to Iran. Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Units (PMUs), staunchly Iran-aligned, have been reported to participate in the quelling the popular ire – paradoxically, the most ostensible conflagrations taking place in Shiite-populated areas. Against such an anti-Iranian backlash, it perhaps seems very naïve to suggest that Iraq will get another waiver after its current 120-day exemption runs out in mid-February 2020, after all, people across the entire country are ransacking buildings of parties linked to Teheran.

Yet with most Iraqi politics moving into a hardly resolvable deadlock, the last thing the country needs is an extension of protests into the energy sphere. Iraq has been playing the diplomatic game well, signing a deal in September to connect into the Gulf Cooperation Council’s electricity grid, by means of a 500MW transmission line that would connect it with Kuwait. However, Iraq’s 10GW power shortfall is simply not going away – every little incremental capacity increase is counteracted by another year of rising demand. Iran’s electricity exports amount to 1.2GW (that’s besides pipeline gas exports), some 7-8 percent of Iraq’s annual demand, yet no one in their sane mind would risk repeating the summer of 2018.

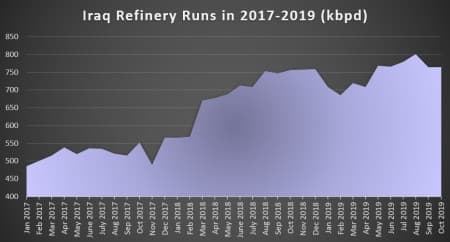

3. Baiji and Kirkuk Might be In Danger Again

Testifying to the difficulties Iraq faces to balance a bloated public sector with post-Islamic State devastation and minimal growth in the non-oil segment of the economy, Haider al-Abadi was ousted from his position of Prime Minister in 2018 despite beating the Islamic State. Defeating the Islamic State allowed the federal Iraqi authorities to further consolidate its power – it has effectively warded off the risk of an independent Iraqi Kurdistan and reintegrated Kirkuk into the national oil distribution system. The victory over the Islamic State also allowed Iraq to ramp up its refinery runs, safely moving into the 750-800kbpd interval lately (with an aggregate capacity of 950kbpd), implying an unprecedented 80-85 percent utilization rate.

Yet the incorporation of Kirkuk’s oil production and the de-risking of the 310kbpd Baiji Refinery are built on fragile foundations – both the Kirkuk and Salah-ad-Din governorates have seen their fair share of protests and both have tangible Sunni populations in a country that has been governed by predominantly Shia leaders. The sectarian facet of the ongoing wave of protests has remained somewhat timid in the north yet might ultimately give the whole story an unexpected twist. Were the Islamic State to resurface and exploit the Iraqi populace’s distrust for its security forces and PMUs, both Kirkuk and Baiji might become battlefields again. They are in erstwhile Sunni territory, both are inextricably linked to substantial money flows and both have been long-time IS targets.

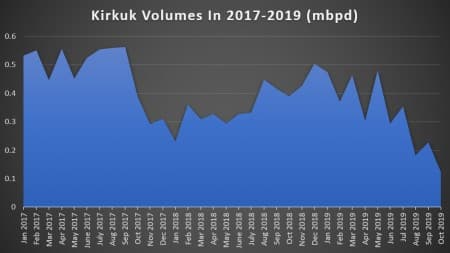

4. Kurds Still Waiting for a Revenue Distribution Deal

Ever since federal authorities retook Kirkuk, Baghdad has been struggling to strike a mutually acceptable deal with the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). According to Iraq’s 2019 budget law, KRG ought to hand over 250kbpd worth of oil production to the state oil marketing company SOMO, whilst the federal treasury would in return pay the salaries of more than 500 000 public-sector employees on the KRG’s payroll. The Kurdish authorities are still yet to hand over a single barrel of their own crude, whilst the federal authorities stick to their strategy of withholding a part of due payments. Add to this pipeline maintenance works in early October and one gets a firmer grasp of why Kirkuk volumes, in general, have been falling throughout 2019.

With nationwide protests occupying much of the government’s attention and a potential election looming on the horizon, the Kurdish issue (“as old as the state of Iraq itself”, in the oft-quoted words of Adil Abdul Mahdi) will be inevitably put on the back burner. This is bad news for Erbil, all the more so as the current setup of the Iraqi government was largely perceived as the most Kurdish-friendly in ages, with an ethnic Kurd at the helm of the Finance Ministry. The oil marketing issue is just a fraction of a plethora of discrepancies – the largest being the KRG’s federal budget allocation, dropped from 17 percent in 2014 to 12 percent this year (and still not being paid properly).

5. Western Investors Will Delay Their Iraq Entry

According to Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index of 2018, Iraq remains the 12th most corrupt country in the world, beating the likes of Haiti, Congo or Central African Republic. This obviously hinders economic development yet international companies (especially European and Chinese ones) could still find relatively alluring investment opportunities. As recently as September 2019 the Dutch firm Boskalis clinched a deal on the construction of a new crude export terminal in Basrah (coupled with the erection of an artificial island with 6MMbbls of additional storage capacity), whilst the German firm Siemens was tasked to rebuild the Baiji 1 and 2 power plants, bringing them to a production capacity level of 1.6 GW.

In what is already seemingly becoming a tradition, protests in Basrah are more than mere ventings of frustration and usually lapse into all-out ransacking. It is noteworthy that the employees of the Basrah Oil Company have overwhelmingly joined the ranks of protesters, as demonstrators targeted the Umm Qasr harbor premises. The federal government needs a tacit and peaceful Basrah in order to follow through with its infrastructure revamping plans, just as much as it needs Islamic State staying out of northern and eastern Iraq. Given the current turmoil, it is a relatively safe bet to assume that most critical oil and gas infrastructure projects will be delayed by at least 6-8 months as the federal authorities seek to damp down the protests across the country.