What level of profit does a company need to attract financial capital?

Intuitively, business people grasp the idea of tangible expenses such as salaries, rent, and interest expense. But publicly held businesses also raise money in the equity markets. And here, as James Grant of Interest Rate Observer fame has often noted in various contexts, it is Mr. Market who sets the necessary or required level of equity return. And where Mr. Market sets that level depends in large measure on perceived levels of business and financial risk.

A company may not earn cost of capital every year. But shareholders won’t put up money to finance operations if they didn’t think they have a reasonable chance of earning a satisfactory return on their investment. No one invests to lose money. Nor to earn a return below that called for considering the risk taken.

But the regulated utility business is different. Unlike the situation for other private sector corporations, it is the state, and to a lesser extent federal, regulators who in the course of routine administrative hearings establish the utility's rate of return—that is, the amount shareholders can expect to earn on their equity investment. That administratively imposed cap on earnings is the price that utilities pay to retain paid for their monopoly status.

In other words, in a regulated industry the financial discipline that supposedly attends freely transacting entities doesn't exist and has to be replicated. In essence that's what the regulators do. In terms of capital costs, they serve as the proxy for the market.

The utility commissioners and staff endeavor to interpret financial market signals and expectations as filtered through the testimony of often conflicting expert witnesses. Not surprisingly, expert witnesses paid significant sums by parties widely at variance, often offer widely varying expert opinions.

The regulatory arena is also a public one that entails negotiation and posturing. Utilities and their coterie of Wall Street analysts typically claim that regulators set the return on equity too low for the quality of services rendered.

Let’s look at some recent evidence. In its December issue, Public Utilities Fortnightly published an article with the racy title: “2017 Rate Cases Study”. Here are the numbers. Related: UK Gas Prices Rise Most In 8 Years On Explosion, Outages

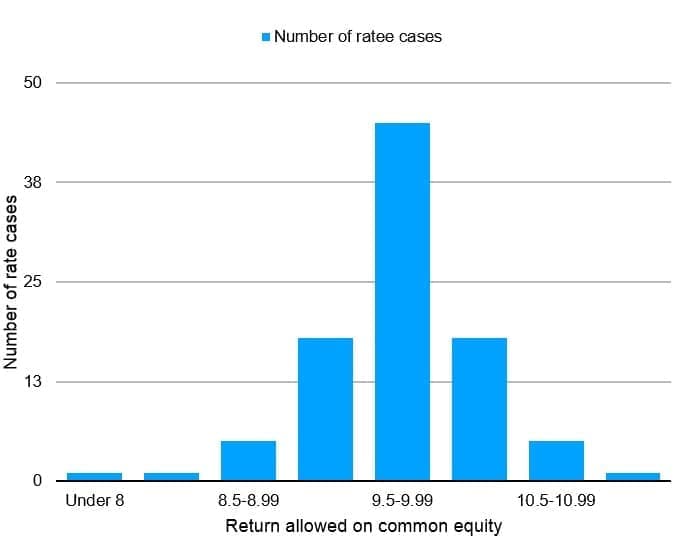

Figure 1 shows a distribution of the returns on equity granted in previous rate cases. Figure 2 shows returns granted in 2017 cases largely for the same companies. In previous cases, regulators granted a return on equity target of roughly 9.9 percent for stockholders’ equity and 9.7 percent in the most recent cases. In both surveys, the bulk of returns are within the 9.5-10.0 percent range. But notice the shift in distribution.

Figure 1. Number of previous rate decisions in each return on equity range

Figure 2. Number of 2017 rate decisions in each return on equity range

Now let’s make a few comparisons. NYU’s Stern business school publishes estimates of cost of equity capital for all major U.S. industry groupings. The latest study showed average cost of equity capital for U.S. businesses is about 8.15 percent. Perhaps in an ultra-low interest rate environment where trillions of dollars in sovereign debt carries a negative interest rate, this is the "correct" level. Who knows? But 8.15 percent is what domestic investors willingly accept as a return on their equity investments. Mr. Market has spoken.

You can find Leonard Hyman's lastest book ‘Electricity Acts’ on Amazon

But this 8.15 percent equity return is a rate for risk tolerant corporations engaged in the rough and tumble of supposedly free markets, not the return required by investors in protected monopolies like utilities. And yes, many investors would gladly accept 8.15 percent per year returns. This leads to the uncomfortable question: Why do regulators think low-risk utilities have a higher cost of equity capital than the average U.S. corporation operating in a competitive environment? Are they being excessively generous with the ratepayer's money?

NYU further calculates that regulated utilities have a cost of equity of roughly 4.59 percent. We know that the standard cost of capital formula does a poor job estimating cost of equity for supposedly lowrisk businesses (a problem that has bedeviled cost of capital theorists for decades). Consequently, we might dismiss an equity return of under 5 percent as unrealistically low, but might reasonably conclude that the real cost of equity for utilities is in the 5-8 percent range. This suggested level is far below the 9.5-10.0 percent equity return levels recently authorized.

Using another typical benchmark, shareholders in general seek to earn roughly six percentage points over the so called risk free rate of return—that’s the yield on a 10-year U.S. Treasury bond, now 2.35 percent. This would equate to a current cost of equity capital of about 8.35 percent, that is, close to the NYU number of 8.15 percent for US industry overall.

Market measures indicate that utility stocks are roughly half as risky as the market. The lower risk profile that utilities offer to investors should at least in theory knock one or two percentage points off of the required equity return. That is, we suspect that utility equities would attract investors even if their earned equity returns were in the lower implied range here of 6.15 percent—7.15 percent.

Looking at the data, we cannot explain why regulators grant the seemingly generous returns that they do. Nor can we predict whether they will continue to do so. Right now, ROE spreads (over and above the risk-free rate) for the U.S. utility industry seem too good to be true. But then again, they have been for decades.

Ultimately, the gap between generous regulatory returns granted and the lower returns needed to raise capital will lead to a problem for a commodity business: higher than necessary prices. Up until now this wasn’t a problem for electric utilities. Customers lacked options other than to pay. Now options have appeared, some priced below the costs of the franchise owning utility. In a commodity business being the high cost producer leads to ruin.

In the electricity business it's already clear that new technological challenges to the existing utility monopoly have emerged. But apart from technology, over the longer term not-for-profit entities like co-ops or government agencies could represent another genuine threat. They operate their utilities sustainably with a far lower financial costs and hence overall operating costs are lower. And these lower costs are in turn passed along to consumers. As regulated utilities continue to be awarded generous returns on equity by state regulators, they become increasingly vulnerable. Inadvertently perhaps, the phrase that to us describes current U.S. regulatory policy is, "through generosity, competitive weakness". Heckuva job they're doin'.

You can find Leonard Hyman's lastest book ‘Electricity Acts’ on Amazon

By Leonard Hyman and William Tilles

More Top Reads From Oilprice.com:

- The Billionaires Betting On Space Travel

- Are NatGas Prices About To Explode?

- Why Is Canadian Oil So Cheap?