For a long time, it seemed that France, Europe’s leading nuclear power producer, will seek to decrease the share of nuclear in its energy matrix. The 2015 Energy Transition for Green Growth law stipulated that by 2025 the share of nuclear would have to drop from the current 75percent (the highest rate in Europe) to 50 percent, whilst capping maximum production capacity at 63.2 GW, i.e. roughly the level where it stands currently. However, coping with the challenges of energy supply proved to be too complex to cut down on France’s traditional buttress, nuclear power – in fact, during Francois Hollande’s tenure not a single nuclear reactor what shut down. Renaming the Energy Ministry into the Ministry of Ecological and Solidarity Transition did not help – with Nicolas Hulot stepping down, nuclear seems to burst back onto France’s energy policy agenda.

France’s nuclear romance started out as a post-1973 crisis realization of the nation’s scarce indigenous resources – it was never really powerful in terms of oil and gas production (currently it produces 16 kbpd of oil and roughly 0.5 BCm of gas on an annual basis but plans to phase out all hydrocarbon production by 2040), the only energy sector it had genuine hands-on expertise in was coal, which employed 150 000 at that time. Nuclear seemed like a perfect match – it was low-cost, carbon-free and France could make use of its Francophone ties with countries filled with uranium, such as Niger. Up until the late 2000s, despite falling reactor construction rates France boasted of the energy independence it reached thanks to developing nuclear as well as its relatively low electricity prices (lower than all of its neighboring countries).

The 2011 Fukushima catastrophe, however, tilted the balance, providing a powerful tool for those who opposed nuclear. Francois Hollande managed to set the nuclear-to-renewables transition in stone, or so it seemed until quite recently. Hollande’s successor, Emmanuel Macron, reiterated his aspiration to carry on with the gradual nuclear phasing out, further underpinning his stance by nominating Nicolas Hulot, a well-known environmental activist and media personality, as France’s first Minister of Ecological Transition and Solidarity. Renaming the energy ministry, however, does not change its substance and the first cracks in the new government’s policy fulfillment began to appear last Autumn. At that juncture then-Minister Hulot postponed the nuclear dependence reduction (to 50 percent of total electricity production) deadline to 2030 or even further.

Related: Europe’s Natural Gas Prices Surge To Record For Summer Season

Hulot announced his stepping down on August 28, in a radio interview, citing general disappointment with the progress of energy policy change. Although the Ecological Ministry had to backtrack on other topics, too, the nuclear issue loomed large in Hulot’s decision to quit – several days before his departure, a confidential report recommended reversing France’s nuclear phaseout and build five new EPR (European Pressurized Reactor, a 3rd generation presurrized water reactor) reactors in 2025 (instead of decommissioning 15-20 reactors). Adding to the probability of an impending nuclear policy reversal as the main cause of Hulot’s leaving, he stated in an interview to French left-leaning newspaper Libération that “if he leaves, there will be 3 another EPRs in the upcoming years”.

Today France has 58 nuclear reactors which are operated by EdF, after the French nuclear champion Areva (now renamed Orano) fully divested its reactor operations in order to concentrate solely on the nuclear fuel business. The root cause was quite simple – Areva’s financial standing was notoriously deficit-plagued and as part of a general reorganization the state has agreed to shelter the newly-established Orano from significant market risks. Only one nuclear reactor was slated for decommissioning so far – in fact, the oldest reactor in the country in Fessenheim – and even this would take place only in 2020, after the first French EPR reactor is started up in Flamanville. The average age of French reactors now is 32 years, which is above the global average of 29-30 years, yet still less than the American median of 37 years.

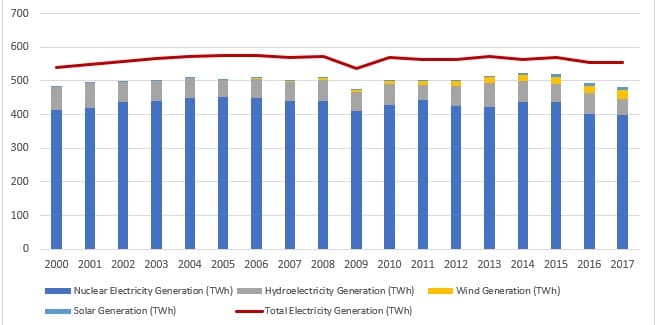

The new Ecological Transition Minister is widely expected to push forward the “transition from nuclear” towards a later date, presumably 2035. The reasons are manifold, yet two main factors can be highlighted – a relative dearth of alternatives to replace the emission-free nuclear and France’s long-standing tradition as one of the world’s leading nuclear pioneers (in fact, only France and Russia can boast of commanding the full nuclear cycle). RTE, the French electricity transmission system operator, proposed last year that in order to compensate for volumes lost due to a potential nuclear phaseout Paris ought to initiate the construction of 20 new gas-fueled thermal power plants, as well as to keep intact the 4 currently functioning coal-fueled plants. Given that 90 percent of France’s electricity comes from emission-free sources (see Graph 1.), this initiative seems even more radical than sticking to good old nuclear.

(Click to enlarge)

Graph 1. Electricity generation in France 2000-2017, by source (in Terawatt-hours).

Related: Airlines Are Suspending Flights Because Fuel Is Too Expensive

Given that renewables currently account for only 8 percent of France’s electricity production, nuclear is the nation’s only choice to avoid any significant energy deficit in the forthcoming years. Aging reactors will have to be replaced with third-generation ones, which are much safer and efficient – despite all the delays and cost overruns (the Flamanville 3 project tripled in cost to €11 billion due to several production faults in the reactor pressure vessel, its current estimated commissioning date is 8 years behind original schedule) the EPR is the most viable way of keeping France’s position as an energy independent country and Europe’s biggest net electricity exporter - bereft of any nuclear capacities, northern Italy is predominantly supplied by French nuclear plants.

ADVERTISEMENT

At some point in the future, when wind capacity has grown sufficiently – both in terms of overall number of wind farms commissioned and their profitability – it might make sense to curtail further nuclear usage, however, under current conditions, it is much more reasonable to get finally rid of coal (which France stopped producing in 2004, so the fuel is imported) and rely on the combination of nuclear, hydro and wind power. Imposing ill-judged restrictions has rarely proven to be the right energy policy tenet, the French nuclear example proves that rationality will prevail in the end, in one way or another.

By Viktor Katona for Oilprice.com

More Top Reads From Oilprice.com:

- Mexico’s Dramatic Energy Reform

- Why Oil And Natural Gas Prices Are Diverging

- Oil Prices Inch Lower As Rig Count Rises

There are two circulatory systems in the reactors. The first is the hot water sealed system that is turned into steam to run turbines then condensed back into the water through the heat exchanger. The heat exchange system is open drawn from the rivers and circulated around the hot tubes to condense the steam back into water then, the cooling water is returned to the rivers.

The problem lies in physics, it takes a whole bunch more cooling to make a hot source cooler and a whole bunch more if your cooling water is already warm.