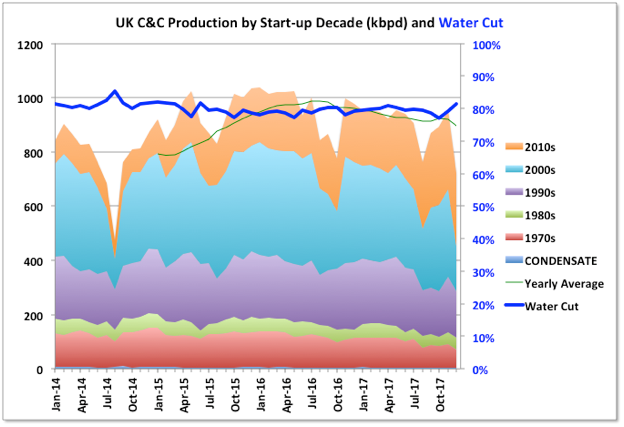

2017 trends for UK offshore production were disrupted by the stoppage in the Forties pipeline in December, which took several hundred thousand barrels of oil equivalent per day off line. Overall average oil production for the year dropped 61 kbpd (6.4 percent) and natural gas (including NGPLs) barely changed with an 800 boed drop. With the Forties issue exit rates don’t mean anything, but the running average oil production was on an upward trend in the second half of the year, which will continue through 2018, barring further major outages, while natural gas was noticeably declining and might struggle to maintain 2017s rate this year.

2016 reserve numbers fell for both oil and gas with few discoveries and some negative adjustments. Oil and gas production will decline from 2018, with accelerated falls from sometime in the mid-2020s without major new discoveries (which may include onshore shale gas, but that is not covered here).

UK C&C

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

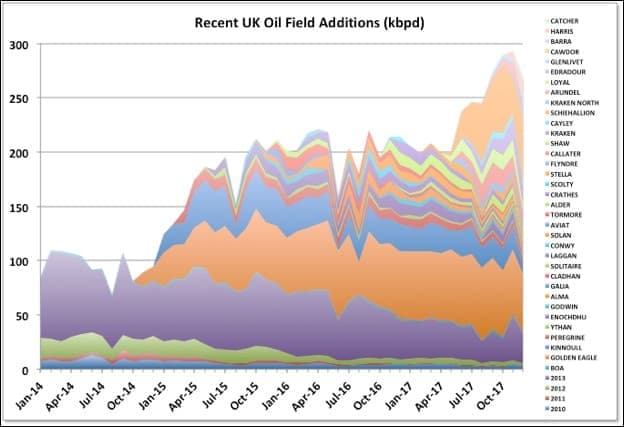

Through 2015 and 2016 a lot of smaller, short cycle developments came on line as a result of the boom from the high price years from 2011. Now larger projects started in those years are ramping up. The largest is the Glen Lyon FPSO, which is part of a revamp of two mature fields: Scheihallion and Loyal. Additionally, at the end of 2017 Kraken, Catcher (including Burgman and Varadero fields) and WIDP (for fields Harris and Barra) were started and will continue to ramp up through early 2018. Clair Ridge was commissioned in late 2017, it has dry trees and a single platform drilling rig; production will ramp up as the wells are completed (they may need to complete production/injection pairs before being able to produce from each block, which may slow things down a bit). Statoil’s heavy oil field, Mariner with nameplate 55 kbpd, will also start up in 2018, after some delays. The Captain field has started trials of polymer injection, which is intended to ramp up through 2021, and, if successful, will maintain current production rates at around 25 to 30 kbpd.

The availability from some of the larger, mature producers seems to be increasingly impacted by unplanned outages, possibly just due to chance or their age, but maybe also impacted by cost cutting in response to the price drop in 2015. Apart from the Forties pipeline issue, in January the Chevron-operated Erskine field was taken offline by a wax pipeline blockage while pigging, there have been a couple of instances of fields being partially evacuated because of water quality issues, and the Ninian platform was evacuated ahead of a major storm because of doubts over its structural integrity.

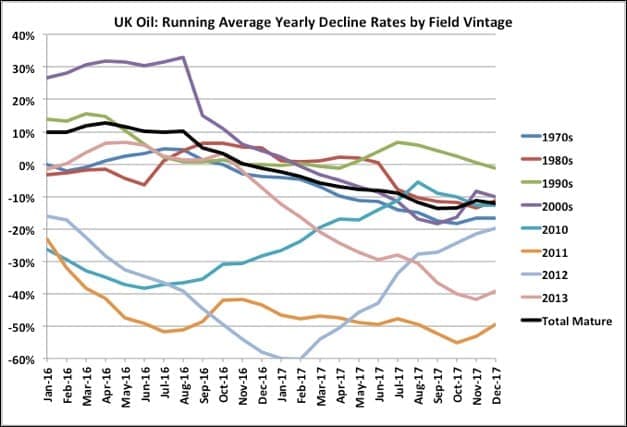

Mature Field Decline

(Click to enlarge)

Mature field production rates of change have moved from positive (i.e. increasing production) in 2016 to negative 10 percent in 2017. The increase in production in older fields was due to in-fill drilling and brownfield developments, especially on the larger, mature projects many of which had been sold off by IOCs to smaller independents. The excellent performance of Buzzard, which has stayed on plateau several years longer than expected, should also be highlighted. However, while in-fill drilling can lead to increased recovery, although the recent negative overall growth numbers would suggest there hasn’t been much of that, it always leads to increases in later decline rates.

Related: Escalating Trade War Ups Pressure On Oil Prices

I have not included Scheihallion and Loyal as mature fields as they are being redeveloped through the multi-billion-dollar Quad 204 project, with the Glen Lyon FPSO, and their production increase doesn’t represent normal field behavior (and it could be argued this need represents some poor decisions by BP when the fields were first developed, rather than improving recent performance). With them, however, the overall 2017 rate would have still been slightly increasing.

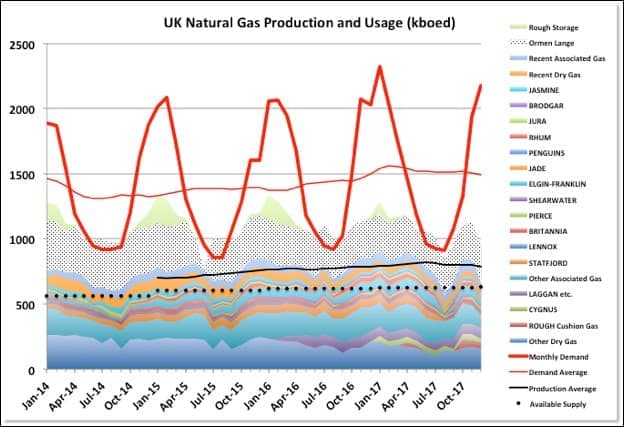

UK Natural Gas

(Click to enlarge)

Produced natural gas is in long-term decline. Most gas now is associated with oil fields. Ormen Lange is a Norwegian field, but exclusively and continuously, supplies UK so I’ve included it here. Demand is highly seasonal, supply less so but still usually shows a dip in summer when some fields are taken offline for major turnarounds. In previous years Rough long-term storage was used to store excess production in the summer and release it in winter, but that was stopped this year (note that in the chart the total production for sale is not net as the gas used to fill the store is not removed from production in previous months).

The supply figures show reported production from fields. Actual gas available for sale is less than that reported per field because shrinkage from use as fuel gas, flaring, and NGPL extraction need to be removed. Unfortunately there isn’t enough data to be able to correct accurately for these numbers against individual fields so I’ve left things as they are and shown the UK governments reported yearly natural gas sales. I don’t know why the gap between reported production and sales has widened, but it could be to do with richer gas fields coming on line.

Recent Start-Ups

(Click to enlarge)

The chart above shows the larger recent gas additions from dry gas, gas-condensate and oil fields in more detail. The largest dry gas field is Cygnus. It flowed about 50 kboed from Cygnus Alpha, started in December 2016, but is designed to handle up to 90 with ramp-up following Cygnus Bravo start-up in August 2017. Based on the original 2P reserves (636 bcf or 110 mmboe) the field will die in the early 2020s, but there may be additional contingent resources of up to 2 Tcf total.

Rough Long-Term Storage

Overall there has not been enough local supply to meet minimum demand, so to fill the Rough long term storage has required other import from Europe (which mostly ultimately comes from Norway, particularly Troll). Hence the abandonment of this facility for storage is probably reasonable, at least on straight economic arguments. It is an old field and, although the platforms are in good shape, there have been well integrity issues and it would need extensive workovers to keep functioning, Whether the gas is stored in European or local storage, to some extent, doesn’t matter, as 1) more storage is now available through LNG, and 2) there is not enough pipeline supply to fully fill all long term storage in Europe. However repeated cold snaps like the recent one in March, when supplies were stretched and a lot of coal fired generation was restarted, may alter perceptions.

Although Rough storage is shut down the field is a large, but rapidly declining, supply contributor from October as the cushion gas is blowndown before abandonment and decommissioning (reserves are estimated at 320 bcf or about 60 mmboe).

Here are two papers with more details on the Rough storage shut down, written before the final abandonment decision was made: Oxford Institute for Energy Studies and Competitions and Market Authority. The second one also contains details on the future issues with UK natural gas supply, which aren’t particularly comforting for a UK resident.

Future Production

Culzean, a largish HPHT, gas-condensate discovery in the Southern North Sea with reserves of 275 mmbbls, is expected on stream in 2019, with rates of 60 to 90 kbeod, which would see it through to around 2030. Overall though, without several large, and improbable, new discoveries and developments, the UK will be highly dependent on imports of natural gas from the mid 2020s, and at a time when supplies from Norway and Holland will be in decline and global LNG demand likely to be growing significantly. See below for a projection scenario for UK natural gas supply.

(Demand and net supply data is from DUKES -Digest of UK Energy Statistics).

Shetland Gas Plant

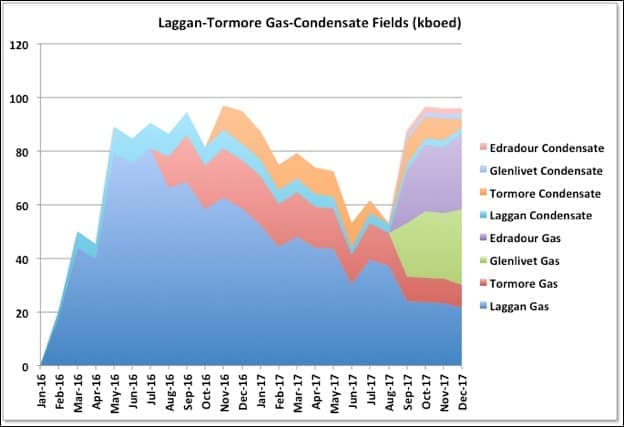

The Shetland Gas Plant (SGP) in Sullom Voe is a Total operated facility receiving production from gas-condensate fields West of Shetland. The largest of these are Laggan and Tormore. Combined they had original reserves estimate of over 230 mmbbls (1 tcf), but they certainly don’t seem to have been operated like that. I don’t know if the Laggan-Tormore project has been having problems but production seems to have declined rather quickly since these fields started up in early 2016. Combined the fields only reached the design capacity of 90 kboed for a couple of months and have been declining at about 50 percent year-on-year through 2017. In December they were down to 35 kboed.

Edradur-Glenlivet are smaller gas-condensate fields in the same area and have been started this year feeding into the same pipelines and processing facility. It looks like they are being ramped up as the other two fields decline to maintain the gas plant at capacity; if so both the new fields are likely to run out of well capacity pretty soon. It’s possible that Laggan-Tormore drilling has been delayed to allow for early production of the other fields, but that would not normally be an optimum development choice; it should become obvious either way fairly early this year. An early decline in production will leave quite a hole in UKs expected production.

(Click to enlarge)

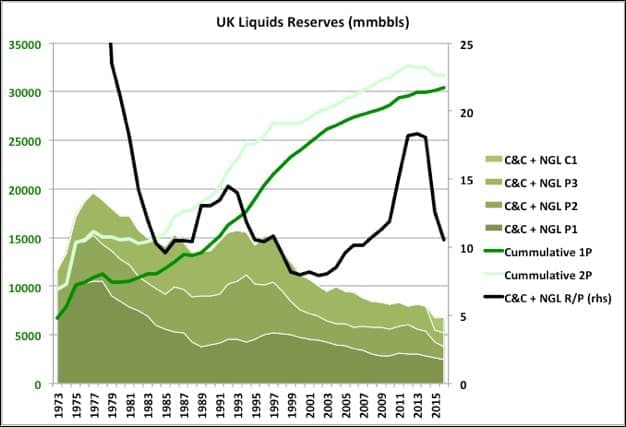

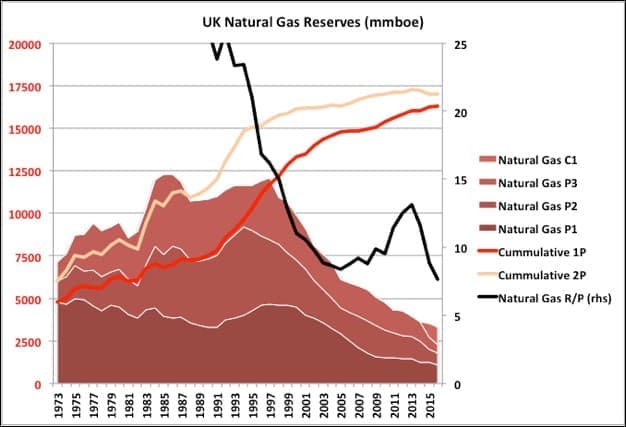

UK Reserves

The, now defunct, UK DECC ministry used to issue a downloadable reserve history, updated each year, but the UKOGA has stopped that and only issues the current year’s numbers with a historical chart in a pdf file. Therefore I’ve used the previous numbers up to 2015 and added the 2016 numbers from UKOGA. Note that the numbers here include a small onshore component.

Both oil and gas remaining reserves are in decline, gas in particular quite steeply, and even overall negative revisions have slightly exceeded discoveries recently. The figures are for the end of 2016 so another year’s production for 2017, and with no much addition from new discoveries or newly approved projects, would take the R/P number for gas down to around 5.5 for this year. Related: 2018 Oil & Gas Projects To Break Even At $44 Per Barrel

The move of possible reserves (less than 50 percent chance or recovery) to contingent resources (less than 10 percent) was made last year. I’ve only shown 1C numbers but there are also 2C and 3C values reported, which is where a lot of the potentially large extra recoveries mentioned in some recent studies, and linked elsewhere here, are held.

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

The UKOGA also recently published an updated estimate for expected total recovery and production projections. They indicate 11.7 Gboe to be produced from 2016 to 2050, which would include all the 3P reserves given above plus another 3 Gboe from new discoveries or development of existing contingent resources (many of these are in small discoveries below 10 mmboe, and/or in rescinded leases). I think that might be a challenge, and as a minimum would require sustained oil (and equivalent gas) prices well above current numbers, plus the longer it takes to develop these projects the fewer available tie-back hubs there will be, and none of these small pools can be developed in isolation. However a report from the Aberdeen University Institute for Energy indicated $60 oil would still allow development of the smaller fields (as $60 oil is behind us that theory might never be tested now).

UK 2018 Plans

Drilling

2017 had the lowest number of wells drilled since 1973, with 14 exploration, 9 appraisal and 71 development. Baker-Hughes numbers give UK offshore rigs for February at five for oil and one gas. The numbers have been generally trending down since the late nineties, with a few boom and bust related peaks and troughs. The 2015 price crash didn’t register particularly in the trend though.

In the last lease round there were only three bids, all from a Statoil/BP venture, with committed wells, the others were for seismic evaluation with a contingent well or drill-or-drop arrangement. All other wells to be drilled would be dependent on economic evaluations for appraisals or development, maybe with some in-fill drilling though a lot of the opportunities for that might have been used up though the 2011 to 2014 boom years.

Recent announced discoveries have been small: Vebier (Statoil, 25 to 60 mmboe), Capercaille (BP, light oil and gas-condensate), Achmelvich (BP, oil) and Garten (Apache, 10 mmbbls). They are likely all to be tie-backs or outreach wells if developed. So far this year six wells have been reported dry or with non-commercial show, three appraisal wells have been discoveries and four wells are held tight, with two looking promising and two maybe not so much (data from Discovery Digest).

Overall there isn’t any indication that drilling activity is likely to pick up much, but the next (30th) lease round, due this year, will make things clearer.

ADVERTISEMENT

Development

Rystad recently indicated a probable number between 12 and 16 for new oil and gas projects to be approved this year, targeting about 450 mmboe. Most of these will be small tie-backs. The largest project is likely to be the Rosebank FPSO for Chevron, which has been around for some years and appears to be quite a difficult, multi-layered reservoir and would produce 100 kbpd from 300 mmboe reserves. Penguins is a second FPSO and has been approved by Shell. It is a reuse of an existing vessel and will complete the exploitation of the Penguins gas-condensate fields. It is required as these are currently tied into Brent Charlie, which is being shut down. After these two there isn’t much of the 450-reserve base left for the other 10 to 14 projects so they will all be developments few wells, and mostly rapidly declining.

The Hurricane Lancashire basement oil development is being progressed and will use a leased, repurposed FPSO for an early production system to check for expected recovery. One of the successful appraisal wells this year was associated with this field.

Decommissioning

Decommissioning is the big growth area in the UK oil sector with 148 fields due to stop production between 2018 and 2022, and 84 between 2023 and 2028. That latter figure is likely to grow as most new projects in the next couple of years will be short-cycle developments with ends of life in that period.

UK 2018 Production Projections

(Click to enlarge)

This oil projection includes all currently producing fields, those in development (in upper case) and those named, and on E&P companies’ books. The numbers shown in parentheses are for expected nameplate capacities. Start-up dates are taken from company releases, ramp-up times and plateaus are based on type of development and decline rates are tuned to match total reported reserves. For the producing fields decline rates are matched to recent numbers and tuned overall so total production to run out equals the 2016 2P reserves (but I left the NGPL numbers in, so there is really a bit of growth). The potential developments and “others” are mostly guesses and decline rates are tuned overall to give a total of around the current 3P resource number. The secondary peak in 2024 is mostly from Rosebank and some heavy oil or base sediment possibilities – it may be smoother than that, or might have much lower overall production. Overall, by this scenario, 2018 has slightly higher production than 2019, but a bit less than 2016.

The IEA numbers have an average of 1100 kbpd for 2018/2019 dropping to 900 kbpd by 2023. I think they generate their numbers top down from general economic analyses rather than by individual fields. Oil and Gas UK is the UK sector trade body and issues it’s own business outlook each year, which is a pretty good summary of the previous year, but usually a pretty optimistic look ahead. There was another recent report indicating similar high side potential and aspirations from Aberdeen University Institute for Energy.

Modelling scenarios for gas production decline is more difficult than for oil when there aren’t detailed field by field data available. Gas can be associated with oil or come from condensate or dry gas fields. For high-pressure gas fields production can be kept on plateau for a long time and then rapidly collapse. On the other hand, low pressure fields or those with high water or condensate production can lead to more exponential decline. Associated gas tends to follow the oil production curves for oil fields with water injection for voidage replacement (as most of the UK fields are), but there can be a short burst at end of life if a gas cap is present. The UK Oil and Gas Authority treat gas from gas condensate fields as associated gas which makes it hard work to separate out the different field behaviours, and they do not provide individual field reserve numbers, unlike BOEM and NPD.

For Rough, Cyprus, Culzean and Laggen et. al. reserve numbers are available. For other mainly gas fields I approximately prorated reserves using recent production numbers and fitted typical decline rates to match. For associated gas I applied a fixed GOR based on recent numbers to the projected oil production numbers given above. The OGA projections shown have been scaled to account for shrinkage between platform production and final sales (see below). The confirmed project production curve, beneath the black line, matches the 2P reserve number for fields currently in production or development (less last year’s production but with an additional allowance for NGLs). The potential field total production is the P3 number plus 250 Gb to allow for the gas discoveries last year.

The production starts to drop quite quickly in the early 2020s and this will coincide with Ormen Lange starting its final decline, as well as continued decline in Groningen as it’s production is intended to be reduced to zero by 2030. If the Laggan-Tormore fields don’t perform as planned the decline could be faster.

The UKOGA February 2018 (stretch target) “vision” projection for future production appears to be a top-down estimate and shows significant growth in 2019 (for oil and gas combined) and then a 4 percent decline, increasing to 5 percent yearly in 2023. I’d say that is highly unlikely on all counts. Their medium-term projections are shown above, but also look like they are based on overall decline rates rather than bottom up field studies, so are a bit low near term, but then too high overall. Note also, just to make things more difficult, they include NGPLs in their numbers, as well as condensate, but on the other hand the pipeline oil, after metering at the platforms, loses some gas when it is treated on shore and the two numbers seem to just about cancel out.

Related: Venezuela’s Oil Sector May Soon Have New Owners

I think the OGA aspirations are less likely here than for oil. To develop the really small gas discoveries requires a high gas price, which in the UK is not fully tied to oil (unlike, say, Japan where natural gas pricing is linked to oil). Ramping up drilling from only one rig would take some time, and rapid new gas development would almost certainly be competing with oil E&Ps for resources. On the other hand, it may be looking that the West of Shetland area is more gas prone so there may be some more significant discoveries to come, and possibly onshore shale gas will prove a success.

Economic Consequences

Sometime in 2018 UK oil production will peak, probably for the last time, and then begin terminal decline. Gas production will show accelerating decline, becoming noticeably steep in the early 2020s unless there are some significant new discoveries and fast-tracked projects. UK productivity is heavily influenced by oil and gas production and will likely decline accordingly. As an indication of what the consequences of continuous decline in oil and gas production might be, this is from an article in the Times in early February:

Forties pipeline closure sends [UK] industrial output tumbling

Industrial output fell by 1.3 per cent between November and December, according to the Office for National Statistics. This was the biggest monthly drop since September 2012 and came after a 0.3 per cent rise in November. The fall was large enough to cause quarterly industrial production to be revised down from 0.6 per cent to 0.5 per cent.

By Peak Oil Barrel

More Top Reads From Oilprice.com:

- How Canadian Drillers Adapt To Extreme Crude Discounts

- Saudi-Iran Proxy War Threatens OPEC Deal

- Are We Sleepwalking Into The Next Oil Crisis?